Quick facts

- Apple trees need at least 8 hours of sun per day during the growing season.

- Two varieties are required for successful pollination; one can be a crabapple.

- Dwarf apple trees will start bearing fruit 2 to 3 years after planting.

- Standard size trees can take up to 8 years to bear fruit.

- Some varieties are more susceptible to insect and disease damage than others.

- Prune annually to keep apple trees healthy and productive.

Two trees can provide plenty of apples

Apples are pollinated by insects, with bees and flies transferring pollen from flowers of one apple tree to those of another. But you don't need to plant a whole orchard to enjoy apples right off the tree. Two trees will reward any family with enough fruit to enjoy and share with friends.

Apples require pollen from a different apple variety to grow fruit. If you only have room in your yard for one tree, there may be crab apples in your neighborhood to provide the pollen your tree needs.

Most apple trees are grafted onto dwarfing rootstocks and only grow to be about 8-10 feet tall. So even if you're short on space, you probably have space for two trees.

Care through the seasons

- March—For existing trees, prune before growth begins, after coldest weather has passed

- April, May—Plant bare root trees as soon as the soil can be worked

- April, May—If last year's growth was less than 12 inches, apply compost around the base of tree

- May, June—Plant potted trees after threat of frost has passed

- May, June—As flower buds begin to turn pink, start watching for insect and disease symptoms

- May through October—Water trees as you would any other tree in your yard

- June, July—Thin fruit

- remove smallest apples to encourage larger fruit

- August through October—Harvest

- taste fruit when it appears to be fully colored

- if it's too starchy, wait a few days

- October, November—Rake up fallen leaves and fruit; compost or discard

- November—Apply tree wrap to prevent winter injury

- November through March—Look for deer and vole damage; put fencing around tree if needed

Selecting plants

Before choosing an apple tree to plant, take a look around your neighborhood. A pollen source should be within 100 feet of the apple tree you plant to ensure the pollen gets to your tree.

If you don't see any crabapples or other apple trees that close, your best bet is to plant two trees of different varieties.

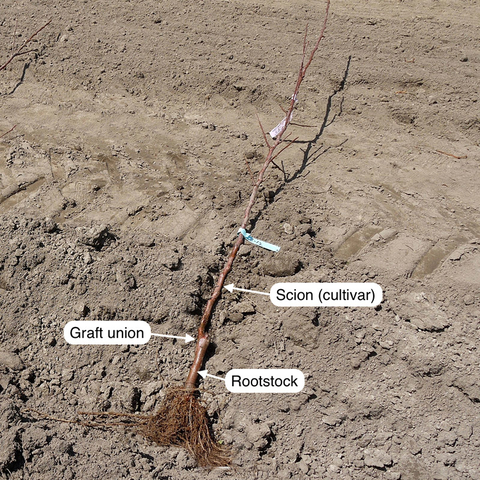

When purchasing an apple tree, you are actually selecting a plant made up of two genetically different individuals grafted together, the scion and the rootstock.

- The scion is the aboveground part of the tree that produces the type of fruit desired (ex. Honeycrisp or Haralson).

- The rootstock plays a major role in determining the tree's ultimate size and how long it will take to bear fruit.

Variety tables provide hardiness, size and compatibility information for apple varieties that have proven to do well in northern climates.

If you have limited space, pay particular attention to the rootstock you choose for your apple trees.

Often nurseries will label the trees dwarfing, semi-dwarfing, and standard. These labels are referring to the rootstock, which determines how tall your tree will grow.

If you have an interest in a specific rootstock, talk with your local nursery. They might be able to order a tree for you.

Otherwise, you might want to order trees from a nursery that grafts each fruit variety on various rootstocks to get the combination you desire.

- Seedling or standard rootstocks may cause the tree to grow 20 or more feet tall.

- Dwarfing rootstocks reduce tree size by up to 50 percent, so that a tree may be only 8, 12, or 15 feet tall when mature, depending upon its rootstock, scion variety, and growing conditions.

- Whether the fruiting variety is grafted onto standard or dwarfing rootstock, the fruit size and quality will be the same.

Seedling or standard rootstock

- Grow to 20 or more feet tall

- Produce up to 10 bushels of fruit per tree

Pluses

- More tolerant of wetter and drier soils

- Better anchored than dwarf trees

Minuses

- May need 8 or more years to start bearing fruit

- More complicated pruning, thinning, harvesting

- More difficult to control pests

Dwarfing rootstock

- Grow to 8, 12, or 15 feet tall (40-80% shorter than standard)

- Produce 2 to 3 bushels of fruit per tree

Pluses

- Simpler pruning, thinning, harvesting

- Easier to control pests

- Require only 3-4 years to start bearing fruit

- Can fit 2 or 3 trees into a small space

Minuses

- Can fall over more easily and may need to be anchored

- May be more prone to some diseases

Common rootstock for Minnesota

Seedling

A seedling rootstock is actually grown from the seed of an apple, often McIntosh or another common, hardy variety. Although you won't know exactly what you're getting with a seedling rootstock—every single seed is a genetically different individual —hardiness, anchorage and adaptability to different soil types are generally excellent.

MM.111

This rootstock, sometimes termed 'semi-dwarfing,' other times 'semi-standard,' produces a tree about 80% of the height of a standard tree. In many areas of Minnesota, this can work out to roughly a 14-18 foot tree.

MM.111 is a hardy, well-anchored rootstock that can withstand drier soil conditions, making it an excellent choice especially for western parts of the state.

M.9 (also: EMLA 9 – virus-free)

This rootstock performs well under many conditions and produces a tree 40-50% the height of a standard tree. It produces fruit very early in the life of the tree.

M.9 has poor anchorage due to brittle roots and a high fruit to wood ratio which means it requires staking for the life of the tree. M.9 is very susceptible to fire blight. It produces moderate amounts of root suckers and burr knots.

M.26 (also: EMLA 26 – virus-free)

This dwarfing rootstock produces a tree 8-10 feet in height. Trees planted on M.26 generally require staking for the first few years of growth or, on windy sites, for the life of the tree.

M.26 is reliably hardy, but is especially susceptible to fire blight. Fruit is produced very early in the tree's life, sometimes within three years from planting.

Apple varieties for home orchards and gardens

| Variety | Hardiness (zone 4 to zone 3) | Avg harvest | Best use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chestnut (1949) | Excellent to very good | Early-mid Sept. | Fresh eating, sauce | Large crab apple, russet skin. Rich, intense, nutty flavor. Fruit stores for 4 to 5 weeks. Moderately resistant to apple scab and fireblight. |

| Cortland | Good to fair | Late Sept.-early Oct. | Fresh eating, cooking, salad | Medium size. Sweet to tart. Slow to turn brown when cut. Susceptible to apple scab and fireblight. |

| Freedom | Good to fair | Sept. | Fresh eating, cooking | Crisp, juicy, sweet. Immune to apple scab, moderately resistant to fireblight. |

| Frostbite™ (2008) | Excellent to very good | Late Sept.-mid Oct. | Fresh eating, cider | Small. Intensely sweet, firm and juicy. Extremely cold hardy. Stores 3-4 months. Good for areas too cold to grow anything else. Some resistance to apple scab and fireblight. |

| Haralson (1922) | Very good to good | Late Sept.-early Oct. | Fresh eating, cooking. Great for pie. | Medium size, striped red. Great for pie. Stores 4-5 months. Some resistance to apple scab and fireblight. |

| Honeycrisp (1991) | Very good to good | Late Sept. | Best for fresh eating. Good for cooking. | Medium-large. Extremely juicy and crisp. Slow to turn brown when cut. Stores well for 7+ months. Some resistance to apple scab and fireblight. |

| Honeygold (1970) | Good to fair | Early Oct. | Excellent for fresh eating. Good for cooking. | Medium size, golden to yellow-green. Crisp, juicy, sweet. Stores 2-3 months. Susceptible to apple scab and fireblight. |

| Liberty | Good to fair | Early Oct. | Fresh eating, cooking | Medium size. Well-balanced flavor similar to McIntosh, but firmer. Immune to apple scab and resistant to fireblight. |

| Regent (1964) | Good to fair | Early-mid Oct. | Fresh eating, cooking | Red striped. Crisp and juicy, well-balanced flavor. Stores 4-5 months. Susceptible to apple scab and fireblight. |

| SnowSweet® (2006) | Good to fair | Mid Oct. | Fresh eating, cooking, salad | Large, bronze-red, blush fruit. Low-acid, sweet flavor. Slow to brown when cut. Stores up to 2 months. Moderately susceptible to apple scab and fireblight. |

| Sweet Sixteen (1977) | Very good to good | Mid-late Sept. | Fresh eating | Medium to large, stripes and solid wash of rosy red. Crisp, juicy, very sweet, spicy, cherry candy flavor. Stores 5-8 weeks. Some resistance to apple scab and fireblight. |

| Triumph (2021) | Very good in Zone 4, not recommended for Zone 3 | Late September | Best for fresh eating. Good for cooking. | Attractive fruit with pleasantly tart and well-balanced flavor and good storage life. Excellent tolerance to apple scab. |

| Wealthy | Good to fair | Early Sept. | Fresh eating, cooking | Medium size, slightly acidic. Resistant to apple scab and fireblight. Doesn't store as long as others. |

| William's Pride | Good to fair | Mid Aug. | Fresh eating, cooking | Medium size, slightly acidic. Resistant to apple scab and fireblight. Doesn't store as long as others. |

| Zestar!® (1999) | Good to fair | Late Aug.-early Sept. | Fresh eating, cooking | Large, crunchy, juicy red fruit. Balanced sweet-tart flavor. Stores 6-8 weeks. Susceptible to apple scab. Some resistance to fireblight. |

University of Minnesota varieties are in bold and include their release date.

Planting and caring for young trees

Learn how to choose a location, prepare for planting and space trees.

Find a sunny location

Apple trees require full sun, so choose a spot where the sun shines directly on the tree for at least 8 hours each day.

Test your soil

When it comes to soil, apple trees can grow in most soils as long as there is no standing water and the pH of the soil is between 6 and 7.

- Have your soil tested to determine pH

- pH of the soil should be between 6 and 7

- Apple trees can grow in most soils as long as there is no standing water

- Avoid planting in areas where water stands for several hours after a rain

If you are unsure about your soil pH, conduct a soil test to determine soil conditions before planting and amend the soil as suggested by the results.

Spacing

How much space do you need for apple trees? A good rule of thumb for a garden fruit tree is to provide at least as much horizontal space as the anticipated height of the tree. So, if your tree will grow up to 8 feet high, make sure there are 8 feet between it and the next tree.

Planting trees too close together will increase shading and reduce the number and quality of the fruit coming from your tree.

Tree spacing

- Standard trees: 20-25 feet

- Semi-dwarf trees: 12-15 feet

- Dwarf trees: 6-8 feet

Dig a hole

- Dig a hole for each tree that is no deeper than the root ball, and about twice as wide.

- When you dig the soil out of the hole, pile it on a tarp or piece of plywood so it's easier to get it back in the hole.

- You may mix in up to one-third by volume compost, peat moss or other organic matter.

- Most of what goes back in the planting hole should be the soil you took out of the hole.

- There is no need to add fertilizer to the hole.

Look at the roots

- If you purchased bare root trees, closely examine the root system and remove encircling roots or J-shaped roots that could eventually strangle the trunk.

- For trees in containers, inspect the root systems for encircling woody roots.

- If woody roots are wrapped around in a circle, straighten them or make several cuts through the root ball prior to planting.

- This helps the plant produce a stronger root system and prevents the formation of girdling roots that eventually weaken the tree.

Put the tree in the hole

- Position each tree so that the graft union is about 4 inches above the soil line. The graft union is a swelling where the variety meets the rootstock.

- If the graft union is placed close to or below the soil line, the variety (scion) will root, causing trees to grow to full size.

- Spread the roots of bare root trees, making sure none are bent.

- Have someone help you get the tree standing up straight.

- Begin adding the soil, tamping to remove air pockets as you go.

- After the hole is filled, tamp gently and water thoroughly to remove remaining air pockets.

- The soil may settle an inch or two. If this happens, add more soil.

Video courtesy of Jon Clements, University of Massachusetts (00:3:47)

How to keep your apple trees healthy and productive

From watering to weeding to thinning fruit, caring for your apple trees throughout the year will help your plants produce plenty of apples to harvest.

Watering

Throughout the life of the tree, you should water its root zone thoroughly during the growing season whenever there is a dry spell. Ideally, the tree should receive one inch of water from rainfall or irrigation every week from May through October.

Support

It's a good idea to stake the tree for the first few years. Either a wooden or metal stake will work. A stake should be about the height of the tree after being pounded two feet into the ground. Use a wide piece non-abrasive material to fasten the tree to the stake. Avoid narrow fastenings such as wire or twine, as they may cut into the bark.

Use tree guards to protect the trunk of your tree

Planting is a good time to install a tree guard. These are usually made of plastic and are available at most nurseries and online.

Tree guards protect your tree from winter injury and bark chewing by small mammals, such as voles (aka meadow mice) and rabbits.

Guards also reflect sunlight from the trunk, which helps prevent the trunk from heating up on a cold, sunny winter day.

- If the bark temperature gets above freezing, water in the conductive tissue under the bark becomes liquid and begins to flow through the cells.

- When the sun goes down or behind a cloud, the liquid water suddenly freezes, damaging the cells and sometimes killing all the tissue on one side of the trunk. This is called sunscald.

Once the tree has rough and flaky mature bark, neither winter sun nor chewing animals can harm it, so tree guards will not be necessary. For the first years of its life, however, it's important to protect the trunk of your fruit tree.

Fertilizer and mulch

Once established, an apple tree planted on a favorable site, in properly prepared soil, should thrive with minimal fertilization.

- Nitrogen is normally the only mineral nutrient that needs to be added on an annual basis and can be added using compost.

- The branches of non-bearing young apple trees will normally grow 12 to 18 inches per year while the branches of bearing apple trees will grow 8 to 12 inches in a season.

- If growth exceeds these rates, apply no compost at all, as too much growth can keep fruit from developing, and lush growth is more susceptible to fireblight infection.

Weeding

- For the first three to five years, grass and weeds should be removed from about a 3-foot radius around the tree.

- Grasses can deplete soil moisture rapidly and will reduce tree growth.

- Applying a few inches of mulch around the base of the tree will help prevent weeds.

- Keep the mulch a few inches away from the trunk to prevent rodent damage and fungal growth.

An apple tree will provide an abundant crop if conditions are favorable when the tree is in bloom.

Some of the fruit will naturally drop off the tree in mid June, but the tree may be left with more fruit than it can support.

Too heavy crops can cause biennial bearing, when a heavy crop of small, green apples is followed by little or no crop the next year.

- Thinning fruit off the trees by hand will minimize biennial bearing and promote larger, higher quality fruit.

- Leave one or two fruit per flower cluster or, for the best fruit quality, about 4 to 6 inches between fruit on any branch.

- Thin when fruit is about marble size, in late June or early July, after some of the fruit has already dropped naturally.

- Thinning improves the quality of the apples you'll harvest in the fall.

- You'll be more likely to get fruit every year.

See the Farmbytes video Thin apples for better harvests.

Know when to pick

The color of an apple is only one indicator of its ripeness. Sweetness is an indicator of maturity and harvest readiness along with fruit size and color. There is a popular idea that some later apple varieties need a frost to sweeten them before picking. However, apples will ripen and sweeten up without a frost.

How to tell if an apple is ripe

- Look for a change in the background color, the part of the skin not covered with red.

- When the background color (also called ground color) begins to change from green to a greenish-yellow color, the apple is starting to ripen.

- Other than Honeygold, all other apples we recommend should have a green-turning-to-yellow background color when fully ripened.

- Pick a few apples that seem ripe and taste them to be sure they are at the ripeness you prefer.

- As apples ripen, starch in the flesh is converted to sugar. An unripe apple will be starchy and leave a sticky film on your teeth.

- A ripe apple may still be tart, but it should have developed aromatic flavors.

- You may need to pick the fruit from the same tree several times over the course of a week or two in order to get all the fruit at the right stage of maturity.

- Check the UMN Minnesota Hardy website to see what time in the season your apple variety typically ripens.

How to pick an apple

- Gently take the fruit in the palm of your hand, then lift and twist in a single motion.

- Or use one hand to hold the short, thick fruiting spur that bore the apple, and the other hand to lift and twist the fruit.

- Avoid pulling or yanking the fruit as you could pull off the spur, taking with it next year's flower buds.

Storing apples

Apples last the longest at standard refrigerator temperatures, about 33°F to 38°F, with about 85 percent humidity. Although garages, basements and root cellars may provide adequate storage conditions, the best place to store apples at home is usually the refrigerator.

- Warmer temperatures always shorten the storage life of apples.

- Apples stored near 33°F may last as much as 10 times longer than apples stored at room temperature.

- High humidity helps reduce the shriveling of apples in storage.

- If the storage environment is low in humidity, as most refrigerators are, the fruit should be stored in a perforated plastic bag or a loosely covered container.

- Although apples are lovely displayed in a fruit bowl, such conditions will dramatically reduce their usable life.

Will apples be affected by a hard freeze?

A "hard freeze" is defined as four straight hours of 28°F. While 32°F is the freezing temperature for water, it is not the freezing temperature for most fruits. Fruits such as apples, grapes, and strawberries are high in sugar. The sugar in the fruit’s juice reduces the temperature at which the fruit freezes.

- Apple fruit starts freezing at around 28-28.5°F, but apples should be okay provided the temperature doesn't fall much below 28.

- The longer apples are exposed to temperatures below 28 degrees, the higher the chance that they will get damaged.

- Frozen apples should not be picked until the fruit thaws out, as the frozen fruit will bruise and be unusable.

- After a freeze, leave the apples on the tree and wait until midday when they have thawed out.

- Late fruiting apples like U of M's SnowSweet® and Haralson are more at risk of freezing because they are more likely to still be on the trees when a freeze hits.

A brief dip below 28 degrees may just weaken the apples enough to decrease their shelf life. Several nights below 28 degrees are more likely to soften the skin and flesh of the apple, making the fruit unusable.

At 22°F, the fruit will freeze hard and cells will break down, making the fruit soft. If only a brief freeze happens and the fruit is still firm, use the fruit soon, as it may not store well.

Pruning and training apple trees

Prune a tree to have well-spaced branches and a balanced appearance, while eliminating broken, diseased or dead branches.

General pruning guidelines

- Remove diseased, broken, or dead branches

- Remove any downward-growing branches

- If two limbs are crossed, entangled, or otherwise competing, remove one of them completely at its base

- Remove any limbs along the trunk that are bigger in diameter than the trunk

- Remove suckers coming up from the roots or low on the trunk

- Remove vigorous vertical branches, called watersprouts

- Make pruning cuts close to the branch collar at the base of the limb

- For larger limbs, start the cut from the underside of the limb to avoid tearing the bark

- Remove large limbs first, starting with the top of the tree

- "Thinning" cuts remove entire branches at the branch collar and are usually the recommended type of cut

- "Heading" cuts remove only part of a branch and encourage vegetation growth below the cut and are not as common

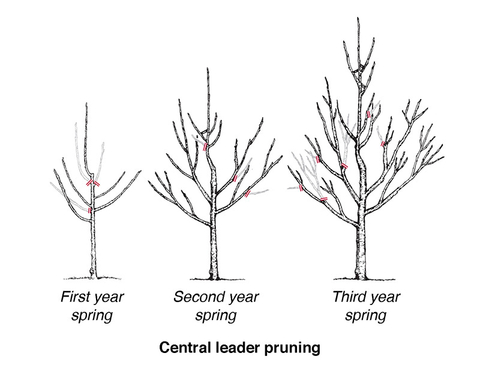

Fruit trees should be pruned every year in late winter/early spring, preferably after the coldest weather is past, and before growth begins. Prune minimally, especially with young trees, as excessive pruning will delay or reduce fruiting and create too much leafy growth.

Once the first set of scaffold branches has been selected, select a second set above it. Scaffold branches should be spaced about 12 inches apart. Always keep the conical form in mind when pruning.

Many apple trees are pruned and trained to allow a central main stem, or leader, to be the foundation of the tree off of which side branches, or scaffolds grow. The tree ends up with a conical or pyramid form. This is called central leader pruning. This is a simple pruning method, and it makes for a compact, balanced, easily managed tree, with fruit that has maximum access to sunlight and air circulation.

How to prune apple trees: A 3-part video series

Have you moved into a house that has an old, overgrown apple tree? Are the branches overlapping and going every which way? Don't lose hope. This tree is probably fine, it just needs a little work to get it back in shape and productive again.

Reclaiming a mature apple tree that has been neglected for several years can be a challenge, and will take a few years of pruning to make the tree productive again. Here are a few guidelines for renovating a neglected tree:

- Decide which branch is or will be the leader

- Then decide which branches you are going to save based on the branch position around the trunk

- At this stage, pruning out a few large branches in year one will open the tree up, increase light and air flow

- Don't prune too much or the tree will put all its energy into making new branches and not fruit!

- During year 2, make a few more decisions on where branches should remain and remove a few more

- Follow the general pruning guidelines to prune out branches that are diseased or broken

As you prune your young tree to achieve a good form, you may also need to train it. Training primarily consists of bending young, flexible branches that are growing vertically into more horizontal positions, toward a 60 degree angle from the main stem. Some apple varieties produce strongly vertical growth and need more training; others tend to produce branches that are naturally well-angled.

- Training branches at about a 60 degree angle from the main stem slows down the production of new leaves and branch growth, and encourages fruiting.

- The more vertical a branch, the more vigorously it grows, and the less fruit it tends to produce.

- Branches that have relatively wide crotch angles are also stronger and better able to support the weight of the crop.

- Branches that grow more vertically often break away from the tree under the weight of fruit.

- Don't train a branch to be truly horizontal or to grow downwards; it should still be growing more or less upwards.

If a young branch is well placed, but has a narrow branch angle, the use of a device called a "spreader" may help. The spreader can be as simple as a notched stick, or you can find them at garden centers. It is wedged in between the branch and the trunk to create a wider angle.

- To train new branches less than six inches in length, use a wooden spring-type clothespin.

- Clip the clothespin onto the leader and position the flexible shoot between the other ends of the clothespin.

- Move the clothespin up or down the leader until you have the young shoot at the proper angle.

- Always go back and remove the spreaders at the end of the growing season.

Managing pests and diseases

Many things can affect apple trees, leaves, flowers and fruits. Changes in physical appearance and plant health can be caused by the environment, plant diseases, insects and wildlife. In order to address what you’re seeing, it is important to make a correct diagnosis.

You can find additional help identifying common pest problems by using the online diagnostic tools What insect is this? and What's wrong with my plant? or by sending a sample to the UMN Plant Disease Diagnostic Clinic. You can use Ask a Master Gardener to share pictures and get advice.

Note that just because you are seeing some damage doesn’t mean all hope is lost. One apple tree will produce a lot of apples, so losing a small number to birds and bugs isn't a reason to stress.

There are several different insect pests of apples, some of which you may see every year, while others you may rarely encounter. Simple activities like removing dropped apples and cleaning up leaf litter in the fall will help manage multiple pests.

Most of the time, apples damaged by insects can still be eaten once the damaged portions are removed.

- Apple maggot can be the most destructive of all the insects that attack apples.

- Codling moth is also a common pest of Minnesota apples, with larvae feeding on developing seeds inside the apple before exiting the fruit.

- Plum curculio is a weevil (small beetle with a distinct snout) that lays eggs on developing fruit, and larvae burrow inside the fruit to feed.

- The shining brown and green Japanese beetle can be found feeding in clusters on foliage and fruit that has already been damaged.

- Apple curculio

Apple curculio feeding damage - Occasional cause of “wormy” and dropped fruit.

- It is a species of weevil; adults have a distinctive snout and are red to brown in color.

- Adults lay eggs inside developing apples shortly after petals fall, which causes scarring on the apple’s skin. If you are treating trees for plum curculio, apple curculio may also be controlled.

- Larvae burrow into the fruit to feed on the developing seeds, causing apples to rot and drop off of the tree.

- Adults wait out the winter in sheltered areas.

- Removing dropped fruit helps reduce next year’s population.

- Spraying for plum curculio shortly after petal fall also manages apple curculio.

The two primary diseases affecting apples in the upper Midwest are apple scab and fire blight.

- The easiest way to prevent these diseases is to plant resistant varieties.

- If you plant susceptible varieties, there are ways to prevent and manage infection.

- Keep the area around apple trees tidy and free of debris, fallen fruit and leaves, pruned branches, and weeds throughout the year.

Apple scab

The first signs of this disease can often be found on the undersurface of the leaves as they emerge from the buds in the spring.

- Apple scab spores are blown around in the air and land on the undersurface of leaves.

- As the leaves continue to grow, both surfaces can be infected as can the fruit.

- The signs to look for on leaves are velvety, brownish, small circles.

- As the infection takes hold, these lesions start to grow together and the surfaces of leaves and fruit become distorted.

Keeping scab infection to a minimum begins with raking and removing leaves from under the tree the previous fall. Planting varieties that are resistant to scab is another way to minimize infection. William's Pride, Freedom, and Liberty are immune to this disease. Honeycrisp has some immunity as well.

If the variety you plant is not immune and you see signs of scab early in the season, the best way to protect the fruit is by covering it with a plastic bag or applying a well-timed spray of organic fungicides such as lime sulfur.

Fire blight

Fire blight is caused by a bacterial infection that can kill blossoms, shoots, and eventually entire trees. You might see this disease on the trunk or limbs of a tree as a sunken area with discolored bark. As the lesion gets bigger, it begins to crack around the edges and the tree will look like it has been burned.

You also might see the disease developing on new shoots as they grow in the late spring. When shoots are infected, they turn from green to brown to black, also appearing as if burned. The shoot will develop a crook at the end of the shoot.

The best approach to managing fire blight is prevention.

- Plant fire blight resistant varieties.

- Plant trees in a spot that is well-drained and has full sun and plenty of air circulation.

- Keep the area around the tree very clean and free of fallen fruit and foliage, pruning debris, and weeds.

Fire blight is most prevalent in young, fast-growing trees. If you see symptoms of the disease, timing is critical because the disease moves quickly through the tree.

- Prune out infected shoots at least 6 inches behind the browning area of that shoot.

- After each pruning cut, disinfect pruners in a dilute bleach solution so you don't spread the infection with your pruners.

- If branches have fire blight lesions, prune those out well behind the infected area. This may affect the look of your tree, but it will potentially save the life of your tree.

- Avoid hard pruning while the tree is young (up to 3 years) and limit nitrogen fertilizers, both of which cause excessive growth.

Small mammals might discover your newly planted apple trees in winter and chew on the young bark. This can be prevented by wrapping the trunk with plastic tree guards or putting a hardware cloth cage around the trunks. Plastic spiral tree guards are easy to use and prevent voles and rabbits from feeding on the bark.

- Push plastic tree guards or hardware cloth cages into the soil to a depth of two inches.

- Loosen plastic spiral guards periodically to allow the tree to expand and to keep moisture from building up around the trunk.

- Once the tree has rough and flaky mature bark, chewing animals will not harm it, so tree guards can be removed.

Deer can also be problematic, chewing on young branches of apple trees or rubbing antlers on the trunks.

- Put a ring of fencing around the tree, especially in winter, to prevent damage.

- Make the fence tall enough so the deer can't reach over the top to nibble branches.

- If you have a lot of trees and significant deer populations, it would be wise to fence your entire planting.

Winter damage

Winter injury is caused when a tree's bark temperature gets above freezing and water in the tissues under the bark becomes liquid and begins to flow through the cells. When the sun goes down or behind a cloud, the liquid water suddenly freezes, damaging the cells and sometimes killing the tissue on one side of the trunk.

White plastic tree guards or tree wrap can help prevent winter injury or sunscald to young trees.

- The white material reflects sunlight from the trunk, which helps prevent the trunk from heating up on a cold, sunny winter day.

- Tree guards can be removed once the bark becomes thick and scaly, after about 6 to 8 years.

- In the meantime, loosen the guard periodically to allow the tree to expand.

- A good practice is to remove the tree guard for the growing season and put it back on in the fall.

Hail damage

Hail is common in the upper Midwest, occurring at times during the height of summer. Depending on the size of the hail, time of year, and duration of the hail event, damage can occur on flowers, fruit, foliage, shoots and branches.

- In many cases damage to the tree itself is minimal, and the tree can usually recover.

- Monitor the tree for any damaged areas that start to change color or spread.

- Hail might cause splits in the bark of shoots and branches, making the tree susceptible to diseases.

- Prune out severely damaged branches immediately.

- Do not fertilize a hail damaged tree. This would result in excessive vegetative growth, and increase the risk of diseases.

- Remove damaged or split fruit as open wounds can attract insect pests and increase chance of disease infection.

- If fruit is dented it should be okay, and is worth keeping on the tree. It may result in a bruise that can be cut out before eating.

Sunburn and sunburn necrosis

Sunburnt apples develop a large brown blotch on the side of the fruit that is exposed to direct sunlight. It is most common for fruit on the southwest side of the tree to exhibit sunburn.

Sunburn may occur during periods of very sunny, hot weather.

Fruits on the outside of the tree are more susceptible to sunburn than fruits on the inside of the tree, because they are not being shaded by as many leaves. However, they also generally ripen faster.

If temperatures exceed 90 degrees F in combination with direct sunlight, apples can also begin to rot at the location of the sunburn. This is called “sunburn necrosis.” Necrosis is not as common as sunburn browning in Minnesota because temperatures do not frequently go over 90 degrees.

Reviewed in 2024