Before we know it, we will be in “snirt” season. Snirt is what we call a mix of snow and soil. You might see snirt in the road ditch, where it looks like someone poured cocoa mix on top of snow. Despite its cute name, snirt is still a sign of wind erosion, a serious problem for gardeners and farmers of all types.

Drought has held on through the summer and fall for a big chunk of Minnesota, and a howling wind in the winter might make snirt mostly dirt. Blown topsoil can hold a lot of organic matter and nutrients that can be released into waterways in the spring. Hungry algae feed on the nutrients in eroded soil, in particular phosphorus. The well-fed algae’s increased growth can lead to major algal blooms that harm the environment when temperatures heat up.

If there are no crops to take up phosphorus, or if there is too much for plants to use, phosphorus builds up over the years. All the more reason to test your garden’s soil.

A lot of residential garden sites have very high phosphorus levels. This is common across Minnesota, as my fellow UMN Extension colleagues have noted. If your garden soil happens to test “very high” for soil phosphorus, adjusting your fertilizer use to avoid building it up is the best single thing you can do to reduce its impacts. However, reducing erosion, even in winter, is a close second.

Tillage tips

Cutting down on tilling or cultivating, especially in the fall, is a no-brainer for erosion control. This goes double for intensive tools like rototillers. The more we break down aggregates physically, the higher the risk of our soil blowing away across the county—or even the country like when a 2019 Texas windstorm dropped soil here in Minnesota.

If you have to cultivate in the fall, keep the surface as rough as possible with big clods of soil. These clods, especially if they have a lot of clay in them, hold together better during winter winds. Bear in mind, clod-making can be hard work but can save you a lot of pain down the line.

Mulch and residues

Simply applying mulch is something you can do, even after a killing frost. Straw or leaves can work fine in slowing erosion. Mulching three to four inches deep should be your goal, and you should be able to rake it away once you start planting in the spring. While it is too late now, combining this tactic with fall garlic planting (which often needs mulch) can work.

In row crop fields, farmers have old residue that they can leave on the surface to slow the wind’s effects. Generally the more residue there is on the surface the better the wind protection. It can also catch snow during the winter, something that helps during drought conditions.

That’s true in gardens too, but be careful about leaving dead tomato plants. There are lots of diseases that can overwinter on residue, especially leaf spot fungi and bacteria on tomatoes. Not rotating vegetable families in your garden further increases this risk.

Cover crops

Cover crops can reduce erosion while bringing other benefits to the vegetable grower. Grasses that have dense root systems tend to be the best choice for erosion protection. Even species that die over the winter, like oats, give you protection through their residue.

Cover crops that survive the winter, like cereal rye, also help and are better for conserving nitrogen in the spring.

No matter what you have grown as a cover, the goal is similar to leaving residue: the more roots, shoots or leaves you have is key. Cover crops sown too late in the fall will not stop anything when frigid winds blow and they are just tiny (maybe even dead) seedlings.

Using cover crops requires careful planning, and success strongly depends on making sure there is enough growing season for them to grow.

Windbreaks

Lastly, windbreaks are always an option. You do not necessarily need rows and rows of trees either. Standing sweet or field corn, tall grasses, snow fences, or even stacked straw bales can help protect a garden.

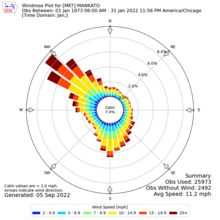

We get most winter winds from the northwest, so make sure the west and north sides are covered. To be more exact in where you place windbreaks, you can use a neat graphic that uses climate data, called a “wind rose,” to see where winds typically come from during a given month. You can find the wind rose nearest to your garden at the Iowa Environmental Mesonet’s website.

With windbreaks, snow (and any soil with it) is captured just past and in front of the barrier. Collecting extra snow for the spring can be helpful in some cases such as drought.

Having a snow drift that is too close to a house or driveway can be a pain. There are windbreak designs that can adjust how snow is collected; dense windbreaks keep drifts in a narrow area and more open windbreaks spread the snow out evenly.

Please note that while sparse looking windbreaks may limit deep drifts, they do not hold back a lot of snirt. Similar to cover crops, effective windbreaks take some homework beforehand. You should consult with UMN Extension or your local Soil and Water Conservation District if you want to put in a permanent windbreak that can protect more than a small veggie plot.

Soil is so valuable to us and yet it is so easy to take it for granted. If you can make use of all of the ideas above in your garden, great! If not, that is OK too.

As the last few years have shown, stuff happens. An early freeze or drought can kill your cover crop before it can do anything. Deer might eat those white pines you put up as a windbreak. The straw you brought over could accidentally bring weed seeds with it. But by diversifying what you do to stop your soil from turning into snirt, one or two setbacks will not scatter all your efforts into the wind.

- Brandle, J. and Nickerson, HD. (1996). Windbreaks for Snow Management. University of Nebraska Extension. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natrespapers/125/

- Iowa Environmental Mesonet. (2022). IEM Site Information - Minnesota. Iowa State University. https://mesonet.agron.iastate.edu/sites/locate.php?network=MN_ASOS

- Lyon, JD. and Smith JA. (2004). Wind Erosion and Its Control. University of Nebraska Extension. https://extensionpublications.unl.edu/assets/html/g1537/build/g1537.htm

- Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. (2022). Blue-green algae and harmful algal blooms. https://www.pca.state.mn.us/air-water-land-climate/blue-green-algae-and-harmful-algal-blooms

- Pugh, B. (2022, October 13). Minnesota. National Drought Mitigation Center, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?MN

- Samenow, J. (2019, April 11). Minnesota’s pristine snow has turned the color of dirt. It can thank Texas. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2019/04/11/minnesotas-pristine-snow-has-turned-color-dirt-it-can-thank-texas/