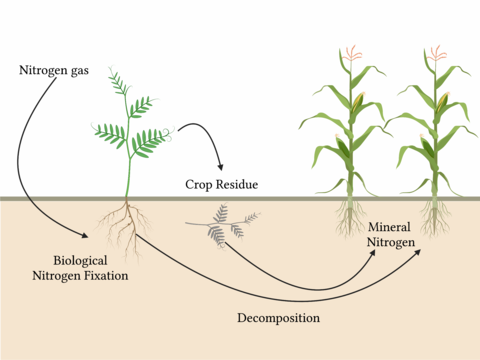

Nitrogen is critical for plant growth and development. Most plants take up nitrogen from the soil, but the legume family of plants can take nitrogen directly from the air (air is almost 80% nitrogen gas).

Legumes can’t do this alone, however. They need soil bacteria called rhizobia to engage in the process of biological nitrogen fixation. In this process, rhizobia form specialized organs on the legume’s roots called nodules, which are ideal environments for the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen into a nitrogen form the plant can use. This makes legumes like soybeans, lentils and chickpeas valuable sources of protein as well as valuable sources of soil nitrogen fertility.

Are my legumes fixing nitrogen?

To check whether your crop has been successfully nodulated, you should check the roots for nodules.

- Nodules that are actively fixing nitrogen will be pink, because of a substance rhizobia produce called leghemoglobin, which keeps the nodule in a low-oxygen environment.

- Inactive, ineffective nodules will be white in color. They are a sign that the rhizobia in your field are not providing sufficient N for your plants’ growth and development.

When should I inoculate my legumes?

Rhizobia are common soil bacteria and can stay in the soil for a long time. However, there are many different species (238, to be exact). The legume-rhizobia relationship is very specific, so not all rhizobia can form nodules on all legumes. For example, the Bradyrhizobium japonicum species that nodulates soybeans is not an appropriate partner for field pea, which forms associations with Rhizobium leguminosarum.

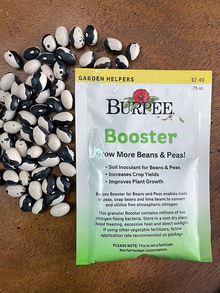

It is important to choose the right inoculant for the legume species you are planting, or nodules will not form. Be sure to check that the plant you’re growing is listed on the inoculant package.

If a legume was previously inoculated and grown in a field, it is likely that field contains rhizobia. Rhizobia can survive for years in soil when in their dormant state and then be ready to form nodules once a legume is planted.

It takes about 1 million rhizobia cells per seed for effective nodulation to occur, so the field must also have a sufficiently large rhizobia population. Unfortunately, there is no easy way to test whether rhizobia are in your field, other than planting a legume and checking to see if it forms nodules. So it is recommended that you apply inoculant when growing a legume for the first time.

It is also important to keep in mind the rhizobia that persist in the field are not always the most effective at performing biological nitrogen fixation. Rhizobia evolve quickly because genes can pass from one bacteria to another. Often, they evolve to better colonize plant roots (since the plant sends a lot of nutrients to them in the nodules), but they don’t always have the best genes for fixing nitrogen. As a result, it is useful to keep inoculating with recommended rhizobia strains, because rhizobia that have persisted in your fields might not be the most effective.

Cold effects on biological nitrogen fixation

Unfortunately for those of us in the Upper Midwest, it is well-documented that cold temperatures have a negative effect on biological nitrogen fixation. Rhizobia rely on an enzyme called nitrogenase to fix nitrogen, which does not function as efficiently at low temperatures.

These concerns mostly apply to winter annual cover crops, which are planted in the fall. As long as inoculation occurs within the legume’s optimal temperature range (for most cold-hardy cover crops, this is about 15°C/60°F), nodules will form and rhizobia will fix nitrogen before the onset of winter dormancy.

Some research suggests that inoculation with rhizobia actually helps plants survive better in the cold. A recent study on alfalfa showed that when plants were exposed to a cold snap (-6°C/21°F) for 8 hours, plants with active nodules (pink nodules that are fixing nitrogen) survived at a much higher rate than plants with inactive nodules (white nodules that aren’t fixing nitrogen) or no nodules at all. This may be because rhizobia help plants store useful compounds that help them survive the cold.

Even though cold temperatures make it more challenging for rhizobia to do their job, it is very helpful to inoculate legumes that have to face the cold.

How do I inoculate?

You can buy inoculants in small quantities at most local garden stores and online. Many garden and hardware stores sell inoculants in the same areas where they sell seeds.

Inoculants can come in several forms, but the most common is bacteria-infused peat. While it may just look like a dusty substance to the naked eye, there are indeed rhizobia in there.

Because you’re dealing with living organisms, you should treat your inoculant with care. The manufacturer should provide directions to store your inoculant successfully; usually, a cool and dry place, such as a refrigerator, is optimal.

Pay attention to the expiration date of inoculants; applying an expired inoculant will likely not result in the nodulation you want.

The easiest approach for gardeners is to coat seeds with the inoculant mix prior to planting. To do this, combine seeds with the inoculant in a bowl, mixing until each seed is covered. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions on how much inoculant to apply, especially if you have never inoculated crops in your garden before.

Liu, Y. S., J. C. Geng, X. Y. Sha, Y. X. Zhao, T. M. Hu, and P. Z. Yang. 2019. Effect of rhizobium symbiosis on low-temperature tolerance and antioxidant response in alfalfa (Medicago sativa l.). Frontiers in Plant Science 10:1–13.