Successful soybean cyst nematode (SCN) management is a key factor for profitable soybean production. Unfortunately, there is no way to eliminate SCN once it is in a field. Instead, the goals of managing this destructive pest are to:

- Minimize yield losses

- Reduce SCN population density

- Maintain yield potential of resistant varieties with an integrated approach

The most effective SCN management practices currently include using resistant varieties and rotating to nonhost crops.

You can take these steps for making SCN management decisions:

- Monitor yield yearly

- Scout for symptoms

- Take soil samples to determine SCN egg densities

SCN is the most destructive pathogen of soybean in the United States. Annual yield losses in soybean due to SCN have been estimated at more than $1 billion in the U.S. Because the nematode can be present in fields without causing obvious aboveground symptoms, yield losses caused by SCN are often underestimated.

Yield losses caused by SCN can vary from year to year, and are influenced by soybean variety, climatic conditions, and soil biotic and abiotic factors. In heavily infested fields, SCN can cause soybean yield losses of more than 30 percent, and in some sandy soils complete yield loss can occur, especially in a droughty year. In addition, SCN can also infect dry beans and snap beans, and cause significant yield loss to these crops.

Long-term effective management of SCN will rely on an integrated program that includes resistant soybean varieties, crop rotation, and possibly alternative strategies such as soil fertility management and biological control. Although it is unclear whether or not there will be any cost-effective commercial biological control agents on the market in the near future, better understanding of the roles of natural parasites in regulating SCN populations in fields may help to develop strategies to lower SCN populations through practical cultural methods.

SCN life cycle, damage and spread

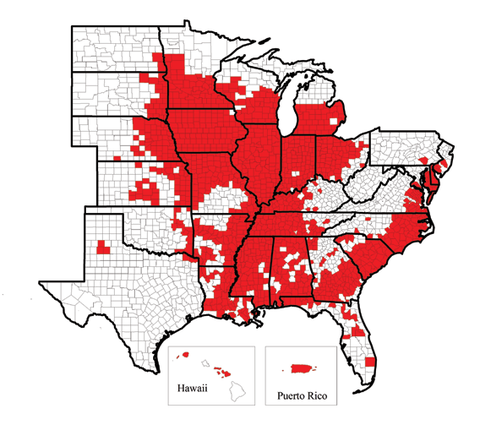

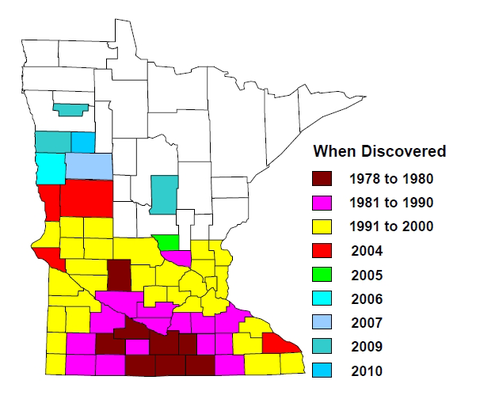

The soybean cyst nematode, Heterodera glycines, has been found in most soybean-producing areas in the world. The SCN was first found in North America in North Carolina in 1954 and since then has spread to at least 31 soybean-producing states (Figure 1) and Canada. In Minnesota, SCN was first detected in 1978 in Faribault County. By 2010, its presence had been confirmed in 64 counties in the state (Figure 2).

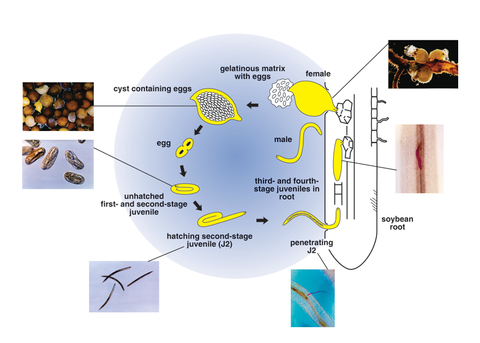

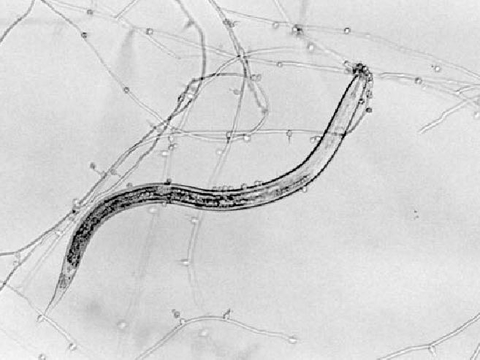

The soybean cyst nematode is a microscopic roundworm that attacks roots of soybean and a number of other host plants. The life cycle of SCN includes the egg, four juvenile stages, and adult stage (Figure 3).

Juvenile stage

The first-stage juvenile develops within the egg and molts to form a second-stage juvenile (J2). The J2 hatches from the egg and moves through soil pores in the film of water surrounding soil particles. It's attracted to actively growing roots and infects by penetrating the host plant root, usually near the root tip.

After penetrating the root, the nematode establishes a feeding site in the vascular tissue, where it becomes sedentary. It then enlarges to become sausage-shaped, and molts three more times before becoming an adult.

Adult stage

The adult female is lemon-shaped. When fully developed, the female's body protrudes outside of the root and is visible without magnification. The adult male undergoes a metamorphosis during the last molt to become a slender, motile worm. The mature male stops feeding and exits the root.

A pheromone released by the female attracts the male for mating. The female exudes a gelatinous matrix from the posterior portion of its body and deposits a small portion of the total eggs that it will produce into it. The gelatinous matrix containing eggs is referred to as an egg mass. Eggs in the egg mass hatch, and the resulting juveniles infect soybean roots the same year they are produced.

The female retains several hundred additional eggs. As the female ages, its body changes color from white to yellow. When the female dies, the body (now referred to as the cyst) changes color to a dark brown. The cyst protects the eggs from environmental damage and serves as the over-wintering and long-term survival structure for the nematode eggs. In addition to the protection provided by the cyst, the egg itself is durable and resistant. Some eggs within the cyst have been shown, under laboratory conditions, to be able to survive for more than 9 years before hatching.

Life cycle length

The length of the SCN life cycle is typically about 4 weeks depending on geographic location, soil temperature, and nutritional conditions. Optimal soil temperatures are 75 degrees F for egg hatch, 82 degrees F for root penetration, and 82-89 degrees F for juvenile and adult development. Little or no development takes place either below 59 degrees F or above 95 degrees F.

In southern Minnesota, SCN can complete three to four generations during a soybean-growing season. In central to northern Minnesota, the nematode probably completes only three generations.

Soybean cyst nematode infection causes damage to plants by physically penetrating and moving through the roots. It also causes physiological damage by altering the metabolism of the root cells surrounding the nematode. These modified root cells, called syncytia, produce the nutrients needed for the nematode's growth and development.

SCN infection also can induce secondary infection by one or more microbial pathogens resulting in a disease complex. As a result, function of soybean roots is reduced, and the soybean plant may show nutrient deficiency symptoms.

Symptoms

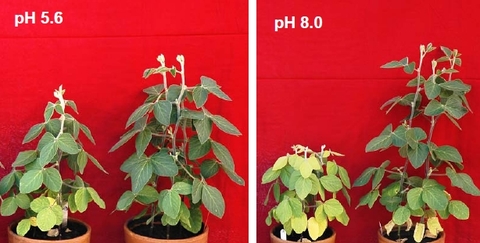

"Yellow dwarf" is an appropriate description for symptoms that are commonly caused by SCN. When soybean plants are severely infected, the plants become stunted, canopy development is impaired, and leaves may become chlorotic depending on soil and weather conditions (Figure 4).

Nutrient deficiency interactions

In Minnesota, iron-deficiency chlorosis (IDC) is a common problem that may be induced or made more severe by SCN infection in high pH soil (Figure 5). Similarly, SCN may induce potassium-deficiency symptoms in soils with low potassium levels. Unfortunately, these symptoms are caused not only by SCN. Other stresses can cause similar symptoms:

- Actual nutrient deficiencies.

- Injury from agricultural chemicals.

- Soybean aphid feeding.

- Infection by other plant pathogens.

SCN distribution in the field

SCN populations are not evenly distributed throughout fields. Severely affected areas with symptomatic soybean plants are often round or elliptical in shape. Those heavily infested areas are often elongated in the direction of tillage, because tillage equipment will spread cysts. These uneven distributions are often observed in a field where the nematode was recently introduced and a field with various soil types.

SCN and nodulation

SCN infection may limit nodulation by nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Because SCN damages roots and limits nutrient uptake by the soybean plants, iron, potassium, and nitrogen deficiencies may increase in severity. Severely infected plants may die before flowering, especially during dry years in soils with poor water holding capacity.

Manage soil fertility

Good soil fertility and adequate moisture increase tolerance of soybean plants to SCN and reduce the severity of aboveground symptoms. Producers may not realize that SCN is present in highly productive fields. Environmental stresses can accentuate the effects of large SCN populations that have developed during previous growing seasons.

What to look for

Look for these symptoms below ground:

- Dark-colored roots.

- Poorly developed root systems

- Reduced nodule formation.

SCN infection may increase susceptibility of plants to microbial pathogens by altering plant metabolism or by creating wounds for other pathogens to enter the plant. Several important diseases to watch for include

- Brown stem rot (BSR)

- Sudden death syndrome (SDS)

- Other fungal root rots of soybean associated with or increased in severity by the presence of SCN.

SCN population density is affected by a number of environmental factors as well as host status. The most important environmental factor is probably the temperature. Consequently, seasonal changes in SCN population densities vary in different geographic locations.

SCN egg populations in the growing season

In Minnesota, after the soil has thawed and temperature increased in April, second-stage juveniles (J2) start to hatch from eggs. After planting soybean, J2 hatch increases due to chemical stimulants from soybean roots.

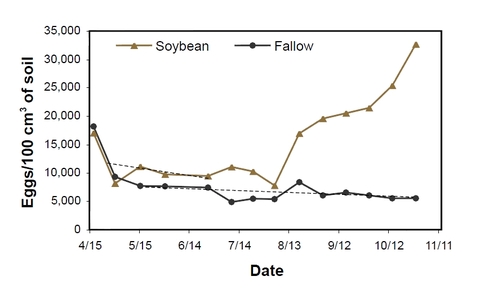

Egg population density in soil declines gradually due to the hatch of J2 until late June to early July when the females of the first generation become mature and produce eggs, and egg population density starts to increase in SCN-susceptible soybean. From late July or early August to the end of the season, SCN egg population density can increase rapidly (Figure 6).

SCN egg populations at harvest

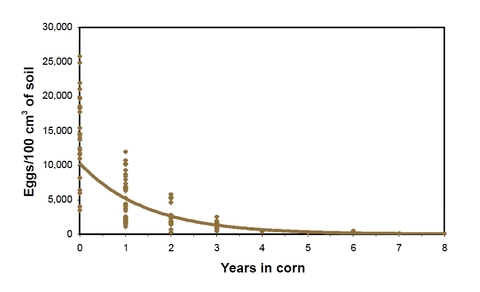

Egg population densities in susceptible soybean at harvest can be as low as a few thousand to as high as tens of thousands per 100cc of soil (Figure 7). Average annual reduction of egg population density in nonhost corn plots is about 50 percent. It takes about 5 years to lower the egg population density from 10,000 to approximately 300 eggs per 100 cc of soil. At this level, there is limited or no damage to soybean.

SCN can move only a few centimeters in the soil by itself. However, soil containing cysts and eggs can be moved long distances within a field or between fields by any means that moves soil. Natural mechanisms that spread SCN include:

- Soil movement in runoff water.

- Wildlife.

- Windborne dusts.

Since the nematode cysts can survive passage through a bird's digestive system, birds may spread SCN over long distances.

Human activities that move soil between fields on equipment, tools, and vehicles are probably the primary means by which SCN spreads. Seed contaminated with soil peds infested with SCN is another way SCN can move long distances.

Geographical spread in Minnesota

In Minnesota, SCN has been reported throughout soybean-producing areas in the southern and central regions of the state. In recent years, the nematode has been found in several counties in the northern soybean-growing areas in Minnesota. Thus, the colder climatic conditions will not limit the spread of the nematode in the Red River Valley where soybean production is increasing. Indeed, frequent flooding in the Red River Valley may favor rapid spread of the SCN in that area.

How to know if you have SCN

In Minnesota, SCN has been found in most (64) soybean-growing counties. However, 50 percent of soil samples near-randomly collected from soybean fields throughout the soybean-growing area in Minnesota in 2007-08 were not infested with SCN or had undetectable low SCN population densities. While most fields in southern Minnesota are infested by SCN, a large proportion of fields in northern Minnesota may have no or low SCN infestation.

Early detection is important for managing SCN and minimizing yield loss to the pest. Determine whether your fields have an SCN problem and how severe it is:

- Look for any plant symptoms in the field.

- Scout females (cysts) on roots.

- Monitor soybean yield.

- Soil sample and test for presence of SCN eggs.

Stunting and chlorosis are typical symptoms of soybean induced by SCN. However, SCN can cause yield loss in the absence of visible symptoms. Declining yields from a field or portion of a field are sometimes the first clue that SCN could be causing a problem. Subtle signs such as areas of uneven soybean heights, slow row closure or expanding, or out of place nutrient deficiency symptoms may also be clues to SCN infestation.

Look for cysts on roots

The most accurate diagnosis of an SCN problem is to find the nematode on plants or in soil. The unique, diagnostic sign of SCN infection is the living mature female nematodes or cysts attached to roots. These tiny, lemon-shaped, white to yellow females usually can be seen on the roots beginning 4 to 5 weeks after planting. The cysts on roots are usually abundant in July and August and then decline in numbers as roots senesce. Visible females on the roots increase and decrease as generations of SCN are produced.

Dig plants carefully

To examine plant roots for presence of females, gently dig rather than pull the plant from the soil to prevent loss of the cysts. Gentle rinsing of soil from the roots in a bucket of water will help reveal their presence. Adult females and cysts are about 1/40 inch long and 1/60 inch wide and are large enough to be seen with the unaided eye (Figure 8). They are easily distinguished from the much larger bacterial nodules on the roots.

Females may be difficult to find on roots under the following conditions:

- The SCN population density is low.

- Sampling is done too early or too late in the growing season.

- The SCN population density is extremely high.

When populations are extremely high, soybean roots that have been severely damaged by the nematode and associated microorganisms will no longer be capable of supporting SCN. Under such circumstances, soil sample analysis by a professional laboratory may be necessary to detect the presence of SCN from these suspect fields.

Soil sampling is an efficient way to determine if SCN is present in a field when SCN is suspected but cannot be observed on roots. This type of sampling can be done at any time of the year when the physical conditions of the soil will permit use of a soil sampling tube or, less desirably, a shovel.

Identify sites

Collect a sample of 10 to 20 one-inch diameter by 6-8 inch long cores from each of several localized "most likely" sites in a field.

- Tillage entry points - One "most likely" site would be a short distance from where tillage equipment enters the field, because contaminated equipment is the number one method of SCN introduction into a property. Infested soil scoured from equipment at such locations allows SCN buildup to begin there.

- Lee-side of a small hill or knoll or along a fence or tree line. Wind-blown soil containing cysts tends to settle out at such locations, much like how wind-driven snow accumulates behind a snow fence or similar obstacle.

- Low areas that flood. A third "most likely" sampling site would be low areas that flood when streams overflow. Egg-filled cysts can be carried and spread by moving water.

Collect from in-row locations

In addition, soil cores should be collected from in-row locations rather than from between crop rows that are 15 inches or more apart because nematode populations are much more likely to be larger in soybean rows than they are between the rows where plant roots are scarce.

Packaging samples

Enclose soil samples in individually sealed plastic bags and submit them to a professional laboratory for processing. Although the dark brown cysts can be seen with the unaided eye, they are very inconspicuous when mixed with soil. The laboratory will use a procedure to "float" any cysts out of a soil sample. Eggs, if any, will be released from the cysts, and counted. The lab's report will report number of eggs per 100 cubic centimeters (approximately one-half cup) of soil.

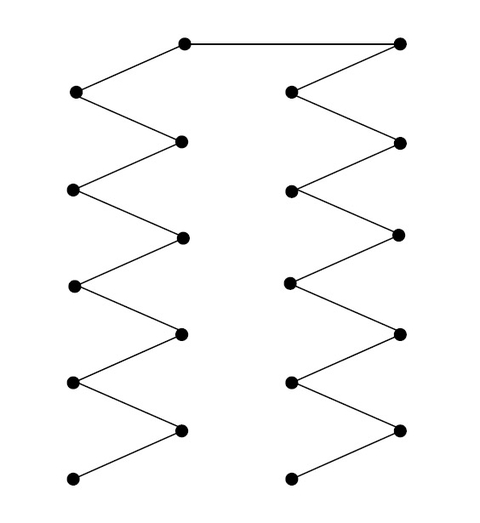

Fields infested with SCN should be managed to minimize yield loss. In order to manage SCN populations effectively, it is important to monitor SCN populations over time. Distributions of SCN are generally uneven in most fields, and nematode egg numbers can vary with sampling technique. So, to minimize the variability for a representative SCN egg count, it is very important to use recommended sampling procedures:

- Divide a field into 5- to 10-acre areas.

- Use a 1-inch-diameter soil probe to collect soil cores to a depth of 6 to 8 inches.

- Collect soil cores from about 20 different locations in a zigzag pattern for each area to be sampled (Figure 9).

- Place the soil cores in a plastic bag.

- Label the sample with field identification using a water-resistant marker.

- Store the samples at a cool temperature if they cannot be sent within a few days to a professional laboratory for analysis.

- If a soil sample is used for both SCN and soil fertility analyses, mix the soil sample thoroughly before sending subsamples to different laboratories.

Factors affecting variability

There are a number of factors that contribute to the variability of egg numbers from soil samples. SCN eggs are deposited in a cluster, and the spatial distribution of SCN in many fields is an aggregated pattern. In some fields, soil cores may contain high egg numbers from hot spots and low, even zero, egg numbers from non-infested or recently infested areas.

How to reduce variability

Increase the number of soil cores collected in each 10-acre area to increase the precision of the sample. You can also reduce the size of the area for each sample. If the hot spots in the field cannot be managed separately from the rest of the field, the best option is to manage the entire field according to the higher population density.

The efficiency of extracting SCN from the soil is dependent on soil characteristics such as texture and moisture content at the time of sampling. Some variability may be associated with the actual laboratory processing of the sample, leading to a rough estimate of the average SCN population rather than an exact measure. However, an effective management program can be implemented using the rough estimate of the average SCN population in a field.

There are other reasons why SCN population densities may vary in two soil samples taken from the same field. SCN egg counts will be highest if samples are collected in the soybean row at the end of the growing season. Due to the variability, it is difficult to compare SCN samples taken from a field at different areas and times of the year.

Have a consistent sampling plan

For long-term SCN management based on soil samples, keep your sampling plan consistent in:

- Area(s) sampled.

- Crop sampled.

- Time of year.

Since SCN egg population densities are reduced during a year when a nonhost crop is grown, SCN egg counts from samples taken after corn harvest, but before soybean planting, are the most useful in estimating potential soybean yield loss. Sampling in the fall rather than spring allows more time for the soybean producer to develop an appropriate SCN management plan.

Soybean variety resistance to SCN

SCN field populations vary in their ability to develop and reproduce on soybean lines that differ in their resistance to SCN. The variability of SCN virulence is described by HG Type schemes. The virulence phenotypes of SCN populations are determined by the number of females that develop on seven indicator lines as compared with susceptible Lee 74 or other suitable susceptible soybean varieties.

Table 1. Indicator lines for HG Type classification of soybean cyst nematode.

| Number | Indicator Line | Example: HG Type 2.5.7 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Peking | - |

| 2 | PI 88788 | + |

| 3 | PI 90763 | - |

| 4 | PI 437654 | - |

| 5 | PI 209332 | + |

| 6 | PI 89772 | - |

| 7 | PI 548316 | + |

How lines are tested

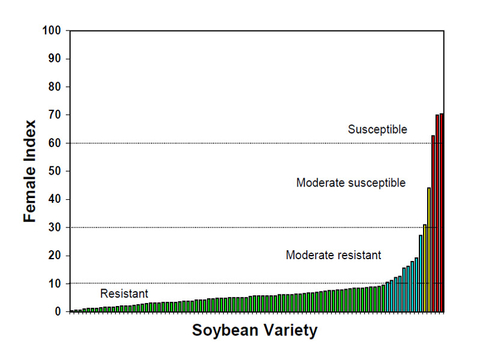

The soybean lines and varieties are inoculated with nematode eggs and maintained in the greenhouse under favorable conditions for about one month. The females formed on the soybean roots are collected and counted. Based on the number of females, Female Index (FI) is calculated:

FI = (number of females on indicator line) × 100 / (number of females on Lee 74).

If the FI is less than 10, the response of the soybean line is "–", and if = 10, the response is "+". The description of HG Type indicates the positive response of a population on the individual lines (Table 1). If no FI is more than 10 on any of the indicator lines, the population is described as HG Type 0.

The frequency distribution of HG Types - percentage of fields with an HG Type - varies in different regions in the United States. In two previous surveys conducted in 1998 and 2002, SCN populations in most Minnesota fields were HG Type 0 or 7 (Table 2), which have a low level of virulence on the current commercial resistant varieties. The frequency of virulent populations in the state may change over time in response to planting SCN-resistant soybean varieties.

Table 2. Percentage of SCN populations from Minnesota with Female Index more than 10 on the indicator soybean lines.

| Soybean line | 1997-1998 | 2002 | 2007-2008 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peking | 3.4 | 1.1 | 15.3 |

| PI 88788 | 13.6 | 17 | 72.4 |

| PI 90763 | 3.4 | 0 | 8.2 |

| PI 437654 | 2.1 | 0 | 0 |

| PI 209332 | 3.7 | 14.9 | 77.6 |

| PI 89772 | - | 0 | 8.2 |

| PI 548316 | - | 33.3 | 94.9 |

Field research: Decreasing level of resistance

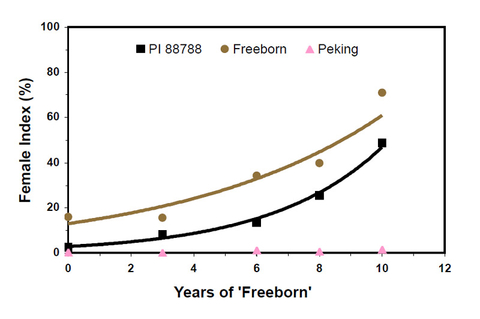

In a field plot experiment, SCN reproduction potential (FI) on the resistant soybean variety Freeborn and its resistance source PI 88788 increased with increasing years of growing the variety (Figure 10).

After 5 years, the population changed from the original HG Type 0 (race 3) to a population that was able to overcome the resistance of PI 88788 (FI > 10; HG Type 2.5.7). After 10 years, Freeborn, which had been moderately resistant (FI ≈ 15) to the original population, became susceptible (FI > 60) to the resulting SCN population.

Alternate sources of resistance needed

Such a change of virulence phenotypes may occur in other fields where resistant varieties have been planted for a number of years. Across Minnesota, the percentage of virulent populations on the resistance source lines PI 88788 and Peking increased dramatically from 2002 to 2008 (Table 2).

Approximately 20 percent of fields in southern and central Minnesota have SCN populations with FI on PI 88788 more than 30, to which PI 88788 varieties are no longer effective. In a few fields (about 2%), the SCN FI are high (>30) on both PI 88788 and Peking. The results of these studies convey a warning that more soybean varieties with alternative sources of resistance are needed for effective long-term management of the nematode in the state.

Test if your resistant variety isn't performing

Based on field observations and recent surveys, SCN populations in many Minnesota fields have become virulent to soybean varieties carrying resistant genes from PI 88788 and/or Peking. If a resistant variety yields poorly or a field has been planted with the same resistant variety or varieties with the same resistance source (PI 88788) for a number of years (e.g., more than 5 years), it is recommended to have the HG Type in the field evaluated.

Scout for cysts

Scouting females (cysts) on the soybean roots in field and testing egg population density after harvesting the resistant variety are also useful methods of determining the reproduction potential of the nematode population on the resistant variety planted in the field.

Be selective on HG type analysis

A complete HG Type analysis including seven indicator lines is time-consuming and costly. To reduce the cost, we recommend only including Peking and PI 88788 because most current SCN-resistant varieties are developed from PI 88788 and a few from Peking.

Although a few varieties with PI 437654 source of resistance are available in Minnesota, we can exclude PI 437654 from the MN HG Type test because none of the SCN populations in Minnesota could reproduce well on it (FI are 0 to 8.8 with the average only 0.4) based on the soil samples collected in 2007-08. Varieties with PI 437654 source of resistance should be effective in lowering SCN population densities in fields.

Besides the designation of HG Type, the Female Indexes on individual lines will be reported (Table 3). Soil samples can be submitted to a professional lab (e.g., the Nematology Lab, Southern Research and Outreach Center in Waseca) for a MN HG Type test.

Table 3. Example of MN HG Type.

| Indicator line | Females/Plant | FI | HG Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peking (1) | 17 | 15.9 | 1 |

| PI 88788 (2) | 19 | 4 | |

| Lee 74 | 107 |

How to manage the soybean cyst nematode

There is no way to eliminate SCN once it is present in a field. Instead, the goals of SCN management are to:

- minimize yield losses

- reduce SCN population density

- maintain yield potential of resistant varieties with an integrated approach

Currently, the most effective SCN management practices are:

- use of resistant varieties (Figure 11)

- rotation to nonhost crops (Figure 12)

You can take these steps, which provide the information necessary for making SCN management decisions:

- monitor yield yearly

- scout for symptoms

- take soil samples to determine SCN egg densities

Many SCN-resistant varieties in Maturity Groups II and I and a few in Maturity Group 0 have been developed and are available for Minnesota soybean producers. Performance of a resistant variety in an SCN-infested field depends on the genetics of both the soybean and the nematode.

Yield potential of SCN-resistant varieties

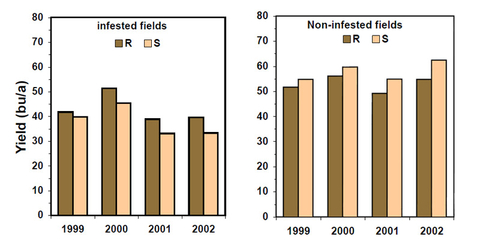

In the past, resistant varieties produced 5-10 percent less yield than susceptible varieties when both were grown in the absence of the nematode (Figure 13). Although current elite, high-yielding susceptible varieties may still outperform current resistant varieties in fields where there are no soybean cyst nematodes or fewer than 200 eggs/100cc of soil, the yield potential of resistant varieties has been improved, and some elite resistant varieties have fairly high yield.

Alternate sources of resistance

Most - around 95 percent - of SCN-resistant varieties are developed from the single source of resistance PI 88788, and a few from Peking and PI 437654. Repeated use of the same resistant variety or continuous use of varieties with the same resistance source may eventually lead to SCN populations that can overcome resistance from the common source. Consequently, soybean varieties with resistance genes from different sources should be alternated to slow changes in HG Type composition and increase effectiveness of resistant varieties.

Determine HG type

If resistant varieties have been used in a field for more than five years, the HG Type should be determined to make sure the varieties are still resistant to the population. Different commercial SCN-resistant varieties have different levels of resistance(Figure 14). Check data of the varieties tested in the greenhouse and local fields, and make sure the variety you will use has a sufficient level of resistance to the SCN population in your field.

Not all the varieties labeled as SCN-resistant are resistant (Figure 14). Data on SCN resistance and yield potential is available as part of the University of Minnesota Soybean Breeding Project's contribution in the annual Soybean Field Crop Variety Trials and at the University of Minnesota Southern Research and Outreach Center website.

Table 4 offers guidance for selecting varieties to manage SCN based on resistant level of a variety and HG Type of SCN from the field. Yield potential is certainly the most important criterion in variety selection.

Table 4. Determine the risk level of using an SCN-resistant variety in a field based on the source and level of resistance of the variety and HG Type of SCN population in the field.

| FI of HG Type 0 on a variety (Variety resistance) | FI < 10 | FI = 10-30 | FI > 30 |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 10 | Low risk | Moderate risk | High risk |

| 10 - 30 | Moderate risk | High risk | Very high risk |

| > 30 | High risk | Very high risk | Very high risk |

Crop rotation is used not only for SCN management, but also to benefit general crop management. Although SCN has a wide range of host plant species, only a few crops are its hosts (Table 5). Many crops, including alfalfa, barley, corn, oat, potato, sorghum, sugarbeet, sunflower and wheat are not hosts for SCN and could be included in a crop rotation to reduce SCN population densities (Table 6).

Table 5. Hosts of soybean cyst nematode

| Crop plants | Weed plants |

|---|---|

| Common and hairy vetch | Common chickweed |

| Cowpea | Common mullein |

| Dry beans | Henbit |

| Lespedezas | Hop clovers |

| Soybean | Milk and wood vetch |

| Sweet clover | Mouse-ear chickweed |

| White and yellow lupine | Wild mustard |

Table 6. Poor hosts and non-hosts of soybean cyst nematode.

| Poor/non-host | Poor/non-host | Poor/non-host |

|---|---|---|

| Alfalfa | Cotton | Rice |

| Barley | Crimson clover | Sorghum |

| Barrel medic | Flax | Sugar beet |

| Berseem clover | Pea | Sunflower |

| Brassica cabbages | Marigolds | Sunn hemp |

| Buckwheat | Oats | Tobacco |

| Bundleflower | Peanut | Tomato |

| Canola | Potato | Wheat |

| Corn | Red clover | White clover |

Non-host years needed to reduce SCN populations

The number of years of nonhost crops needed to effectively lower SCN population density depends on many factors including:

- Initial egg density

- Soil biotic and abiotic factors that affect nematode mortality.

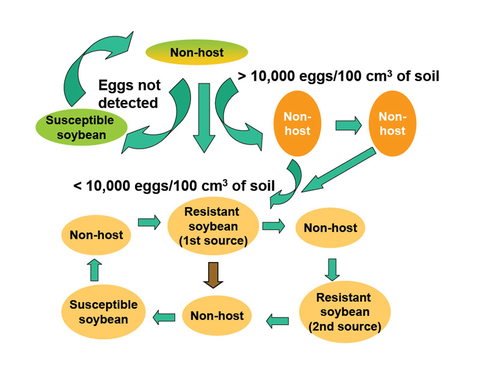

In Minnesota, SCN survives well during winter. With high populations after a susceptible soybean, it may take as long as 5 years - depending on initial egg population density and soil environments - of non-host or poor-host crops to reduce the SCN population to a density (e.g., ~200 eggs/100cc of soil) that will not damage a susceptible variety (Figure 12).

Some leguminous crops such as pea, sun hemp, and Illinois bundleflower are poor hosts that produce SCN hatch stimulants and are more effective in lowering SCN population density than monocots including corn and wheat. Some crops such as marigolds and sunn hemp may produce compounds that have nematicidal effects.

Use resistant varieties

In most cases where soybean is frequently grown in Minnesota, the short rotation period with nonhost crops is not long enough to lower the egg population densities below levels that cause yield loss, and resistant varieties must be used to reduce yield loss.

Egg counts between 200 and 10,000 eggs per 100cc soil

Use resistant varieties when SCN egg counts are in this range of 200 to 10,000 eggs per 100cc of soil.

Egg counts above 10,000 eggs per 100cc of soil

Even with a resistant variety (Figure 15), high densities of SCN can cause a significant yield loss (more than 2 bu/acre) . When SCN population densities are at or above 10,000 eggs per 100cc of soil, plant a nonhost crop for one or more years until the population densities drop below that level.

If rotating nonhosts and resistant varieties reduces the egg number sufficiently, you can use a susceptible soybean.

Suppressive soil

In some fields, because the soil is suppressive to SCN, 3 years of SCN-resistant soybean and nonhosts (Figure 12, brown arrow) may be sufficient to reduce the SCN population to a low level, and you can consider a susceptible soybean. However, determine the SCN population density before planting an SCN-susceptible soybean.

Long rotations

If nonhost crops are planted in rotation with soybean for sufficiently long periods such as in many organic-farming fields, SCN populations can be lowered to less than damaging levels (< 200 eggs/100cc of soil). At low SCN population densities, susceptible varieties can be considered to help avoid or slow down the development of SCN populations that may overcome resistance.

Take measures to prevent or slow down the spread of SCN to areas where the nematode has not been found. This is especially important in the Red River Valley where SCN was more recently introduced, and there are fewer infested fields.

Steps to take

- Plant fields to nonhost crops if SCN is found in only a few fields in an area or county. This is the best option to slow down spread of the SCN to other fields in the area.

- Avoid seed that has been contaminated with soil peds from infested fields.

- On farms where both infested and uninfested fields have been identified, do not use farm equipment (Figure 16) on uninfested fields until the contaminated soil has been thoroughly removed by steam cleaning. While sanitation delays the spread of the SCN, it probably cannot prevent the spread.

Appropriate cultural practices may enhance plant growth, increase tolerance of plants to SCN, and minimize yield losses:

- Maintain proper soil fertility.

- Provide good drainage.

- Control other diseases.

- Control weeds and insect pests.

Insurance pesticide applications are not an effective part of SCN management.

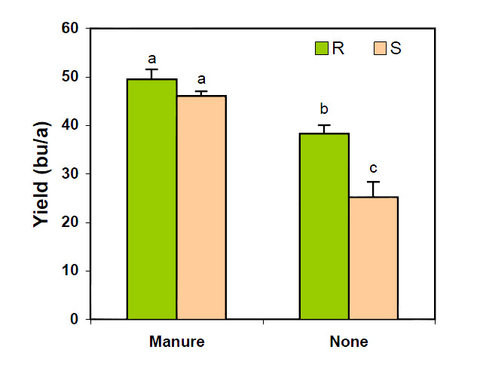

Figure 17 illustrates the effect of soil-applied manure on soybean yields of SCN-resistant (R) and susceptible (S) varieties. Yields of the resistant and susceptible varieties were not significantly different where manure had been applied. However, there was a big yield difference between the variety yields where no manure had been applied. Enhanced soil fertility of the manured plots minimized yield losses of the susceptible variety.

Tillage and SCN

In Minnesota, no-till or reduced tillage does not reduce or has a limited effect on SCN egg population density. In fact, conventional tillage may improve early season root development, and reduce damage to soybean caused by SCN.

These practices, however, do not reduce SCN population density in a field. To limit the growth of SCN populations, they must be integrated in a management program with a rotation of nonhost crops and resistant varieties.

Crop stresses

In some fields, SCN management is complicated by the presence of microbial pathogens and nutrient deficiencies. For example, if chlorotic symptoms are observed in a field planted with an SCN-resistant variety, root rot disease and/or nutrient deficiency (such as iron deficiency) may be involved. In this case, action should be taken to identify and manage all of the crop stresses.

Nematicides

Some nematicides are registered for use in soybean. A few nematicides are effective in lowering SCN population density, but their performance depends on many soil and environmental factors:

- Soil type.

- Rainfall.

- Soil moisture.

- Temperature.

- Soil microbial activities.

Using nematicides significantly adds to production costs and does not guarantee increased yields. Economics, as well as environmental and personal health concerns, should be considered before using nematicides. For these reasons, nematicides are not commonly recommended for SCN management.

Biological controls

Although there is no widely accepted commercial biological control agent for SCN management, biological control should be considered as part of an integrated management program.

Soybean cyst nematode is subjected to attack by a wide range of natural enemies including fungi, bacteria, predacious nematodes, insects, mites and other microscopic soil animals. The species and activities of natural antagonists vary in different fields.

In some soybean fields in Minnesota, high percentages (more than 60%) of the SCN second-stage juveniles are parasitized by the fungi Hirsutella minnesotensis and/or H. rhossiliensis (Figure 18).

Nematode-suppressive soils

SCN population densities are relatively low in some soils due to biological factors, and these soils are known as nematode-suppressive soils.

Some cultural practices may enhance the activities of nematophagous fungi and suppress nematode population densities. For example, monoculture of susceptible soybean for a number of years may increase parasitism of the nematodes by microbial pathogens, and the soil in the field becomes suppressive to the SCN population.

With SCN population densities reduced by natural antagonists, the required time for planting nonhost crops and resistant varieties can be reduced, yield of resistant and susceptible varieties increased, development of virulent HG Type slowed and/or effectiveness of resistant varieties maintained.

Scientists' projections for future of SCN

Soybean production has continued to increase in the past few decades, and it will remain a major crop in Minnesota. Successful SCN management is a key factor for profitable soybean production. SCN management, however, faces serious challenges due to limited sources of resistance, extensive soybean production, and the shift of HG Types.

SCN continues to spread in Minnesota due to unpreventable natural means and human activities. At the present time, more than 40 percent of soybean fields in Minnesota are not infested by SCN or have an undetectable level of SCN. All of these fields have a high risk for SCN infestation. Early detection of SCN in fields is important to minimize its damage to soybean, especially in the Red River Valley, where SCN was more recently detected.

For the next few years, PI 88788 and Peking will still be the major sources of SCN resistance in commercial soybean varieties. With the extensive use of the SCN-resistant varieties from PI 88788, the frequency of HG Type 2-, and the percentage of the fields with an SCN FI > 30 - to which PI 88788 resistant varieties are ineffective - SCN will continue to increase. Within the next few years, the choice for these fields will be to use Peking varieties. Although PI 437654 (CystX) varieties are highly resistant to SCN populations in Minnesota, yield potential of current PI 437654 varieties is still lower than from other sources of SCN resistance.

Peking and PI 88788 carry two distinct types of resistance, and they are good in rotation, at least within a foreseeable period of time. However, it is unclear what the trend of HG Types will be following the rotation of these two sources of resistance. Similarly, it is unclear whether planting Peking varieties in fields having HG Type 2- will change the SCN populations to other Types so that the PI 88788 can be used again or the resulting SCN populations can overcome both PI 88788 and Peking.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota, and other institutions and companies continue to breed for high-yielding soybean varieties with current and new sources of SCN resistance. The development of new, powerful DNA markers and advances in molecular biology will speed up breeding new SCN-resistant varieties. Yield potential of PI 437654 varieties will continue to be improved, and varieties with new sources of resistance will probably be available in a few years.

Long-term effective management of SCN will rely on an integrated program that includes:

- Resistant soybean varieties.

- Crop rotation.

- Possibly alternative strategies such as soil fertility management and biological control.

Although it is unclear whether or not there will be any cost-effective commercial biological control agents on the market in the near future, better understanding of the roles of natural parasites in regulating SCN populations in fields may help to develop strategies to lower SCN populations through practical cultural methods.

Reviewed in 2021