Improving how groundwater is understood makes initiatives to reduce contaminants and conserve natural resources more effective

While 75% of Minnesotans get their drinking water from groundwater held in natural aquifers, not everyone knows what that means.

“Aquifers are not large underground lakes or tanks,” says Anne Nelson, University of Minnesota Extension water educator. “They’re usually made up of large amounts of water flowing in between pore spaces and fractures.”

Nelson and her Extension colleague Taylor Herbert ask people to think of how water would look inside a jar of marbles. They developed a web page, Groundwater and aquifers in Minnesota, that offers a peek beneath the earth’s surface at the many types of aquifers that hold groundwater (z.umn.edu/groundwater).

Naturally, everyone wants to keep excess nitrogen from fertilizer and septic system leakage out of the soil to help keep nitrate levels low in drinking water. Everyone also needs to conserve water to keep it plentiful, especially during times of drought.

The makeup of Minnesota’s aquifers

Understanding groundwater makes people more aware and interested in changing habits that threaten it. Nelson and Becker teach Extension participants about three main kinds of geologic features that hold water in aquifers in Minnesota:

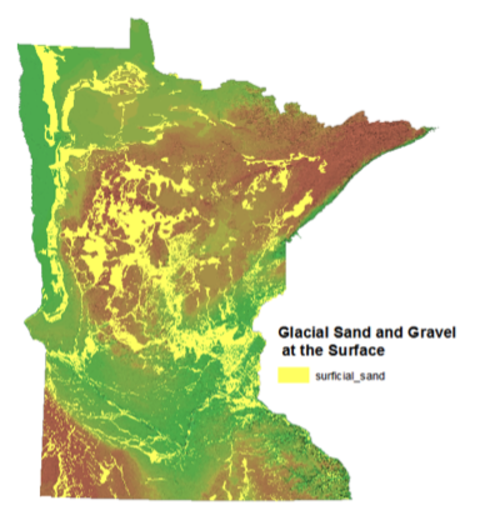

Glacial sands and gravel aquifers

In Minnesota, where nearly all of the state has been covered in ice at one time or another, sand and gravel deposited primarily by glacial meltwater streams is a common aquifer type. These may be at the surface or buried, of limited extent, or covering hundreds of square miles. Most are located in central Minnesota.

Sedimentary rock aquifers

Long before Minnesota was covered in glaciers, much of southeastern and far northwestern areas of the state were covered by an ocean that deposited extensive and thick layers of sand, mud and lime to form sandstone, shale and limestone (or dolostone) aquifers. These are high-yielding regional aquifers.

Igneous and metamorphic rock aquifers

The bedrock underneath all of Minnesota was cooled from a molten state to form igneous rocks (like granite) or was under pressure and heat to form metamorphic rocks (like gneiss, schist or quartzite). These rock types generally do not have primary permeability (pores) but can have significant secondary permeability (fractures). The northeastern part of Minnesota has very little glacial sediment and therefore relies heavily on this type of aquifer.

Starry Trek 2022: The results

2022 marked the sixth year of holding the statewide Starry Trek event to better understand starry stonewort distribution and other aquatic invasive species (AIS) in Minnesota waters.

Starry stonewort is an invasive alga that was first found in Lake Koronis in 2015 and has since spread to 22 Minnesota lakes.

Extension, with the participation of 233 volunteers, visited 248 lakes and rivers. Partners included the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and 24 local organizations hosting local training sites.

Volunteers often search more than one public water access on the same body of water, so the number grows to 289 to count all of the searches.

While volunteers did find 13 populations of previously unreported invasive mystery snails, no starry stonewort populations were discovered during this year’s Starry Trek, although the DNR has confirmed new finds this year.

“Frankly, this year the results from Starry Trek might even be considered ‘boring’ and that’s a good thing,” says Megan Weber, Extension AIS educator. Many of the lakes included in the search are considered “high risk” by Minnesota Aquatic Invasive Species Research Center studies, making this year’s results even more welcome news.

Starry Trek volunteers have discovered nearly 20% of Minnesota’s 22 known starry stonewort populations. Some of these discoveries resulted in successful management actions aimed at controlling the advance of this aquatic invader.