The last few weeks in Minnesota have included blizzards, Siberian air masses and many inches of snow. We’re hunkered down inside, plant roots and seeds are waiting for warmer weather and mammals are looking for something to eat.

But where have all the bugs gone? Both our insect friends and foes have different strategies for surviving a Minnesota winter.

Some insects are “snowbirds”

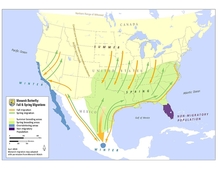

Just like Minnesotans who opt to spend the winter in warmer climates, some insect species choose not to spend the winter in Minnesota. The most obvious example of this is the monarch butterfly, which flies thousands of miles to Mexico each fall. There are also pests with a similar cold weather strategy.

Some vegetable insect pests can't survive a Minnesota winter and instead spend most of the year in warmer climates. They come to Minnesota on weather fronts in the spring and summer, and the winter will wipe out any of the past year’s arrivals. Pests with this type of biology include black cutworm (nocturnal feeding caterpillar that snips seedlings), spotted cucumber beetle and corn earworm/tomato fruitworm (a pest of so many crops entomologists can’t agree on a name!).

Some bugs want to shelter in our place

Some of Minnesota’s newer invasive species seek shelter in our homes. Two common species literally stink.

The multicolored Asian lady beetle is an invasive ladybug species that can be helpful in the garden and in agriculture because it feeds on aphids. But in the fall it becomes a nuisance as large numbers congregate on and in our homes. They don’t pose a risk to us, though they are annoying and produce a strong odor when threatened or crushed.

A newer pest to Minnesota that spends the winter in our homes is the brown marmorated stinkbug (BMSB). Minnesota is home to many native stink bugs; some are predators that help us manage pests. Unfortunately, BMSB is a pest of a wide variety of fruit and vegetables.

Some insects are out here just chillin’

Some insects bear out the winter in leaf litter, tree cavities and in the soil. They may do this as an adult, larvae, egg or pupa. Insects have special adaptations that allow them to survive the cold. They may do this by producing an antifreeze-like substance in their bodies. Others minimize their activity and body functions, almost like hibernation. Some insects are capable of freezing and surviving. Generally, insects do better with snow cover, which can insulate their hiding places, and when temperatures are stable as opposed to fluctuating.

One of Minnesota’s most frustrating pests, the Japanese beetle spends the winter outside. The grub stage of this insect spends the winter in the soil under lawns and other grassy areas. Underneath inches of soil and feet of snow, it seems to do fine in the Minnesota winter.

Some other insects are slightly more vulnerable to cold weather. The codling moth spends the winter as a caterpillar in a cocoon. How well they will survive the winter depends on where the caterpillar weaves its cocoon. Some choose to do so on the bark of the apple tree, which leaves them more vulnerable to the elements. Other caterpillars seek out leaf litter or debris, which gives them more protection, especially once they are insulated by a layer of snow.

Cleaning up the garden after the growing season is over can reduce the places where insects can hunker down for winter. Clean up plant residue and leaves at the end of the season to help reduce the number of overwintering squash bugs, asparagus beetles and imported cabbage worms, for example.

So, does a cold winter mean fewer bugs?

Not necessarily. Insects have many adaptations to deal with frigid temperatures. It is also important to note that windchill does not impact insects, so it feels a little warmer for the bugs than it does for humans right now. As long as we have steady temperatures and snow cover, many insects will do just fine.