Six tips for healthy soil in your garden

- Test your soil.

- Add organic matter.

- Incorporate compost to compacted soil to increase air, water and nutrients for plants.

- Protect topsoil with mulch or cover crops.

- Don't use chemicals unless there's no alternative.

- Rotate crops.

Soil is so much more than dirt. Soil is a living ecosystem—a large community of living organisms linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows.

Every teaspoon of soil is home to billions of microorganisms—bacteria, fungi, nematodes, insects, and earthworms that play important roles.

- Bacteria and fungi break down dead plant and animal tissue which become nutrients for plants.

- Nematodes eat plant material and other soil organisms, releasing plant nutrients in their waste.

- Specialized mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic (mutually beneficial) relationships with plants. The fungi bring hard-to-reach nutrients and water directly to plant roots, and the plants provide the fungi with carbohydrates.

- Worms and insects shred and chew organic material into smaller bits bacteria and fungi can easily access.

- Garden earthworms burrow and create pathways in soil that fill with air and water for plant roots.

- However, they are not native to Minnesota. To prevent spreading them into forested areas, don’t dump fishing bait or move soil with earthworms.

A healthy soil ecosystem provides plants with easy access to air, water, and nutrients. Here are six tips for achieving optimum soil health in your garden:

Test your soil

Understanding your soil is the first step to creating an optimum soil ecosystem. Submit a sample of your garden soil to the University of Minnesota Soil Testing Lab, located on the St. Paul campus.

Your soil test results will include information about soil texture, pH, nutrients, and organic matter, and provide fertilizer recommendations for the plants you plan to grow.

Add organic matter

Organic matter improves soil physical properties such as air and water availability, allowing for healthy root growth.

Organic matter is composed of living plant roots and organisms, decomposing plant and animal residue in varying stages of decay, and enzymes secreted by soil organisms that act like glue to bind soil particles.

As soil organisms like fungi and bacteria break down plant and animal parts, nutrients become available to plants. The plants, in turn, feed the soil organisms with their remains.

Highly decomposed plant material is called humus, a stable and important source of plant nutrients great for growing plants.

Like us, plants need a variety of nutrients for optimum health.

- There are 17 essential nutrients all plants need to grow.

- Macronutrients are needed in larger quantities:

- Carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen come from air and water.

- Nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium come from fertilizer and organic matter; phosphorus and potassium also come from weathering of soil particles.

- Calcium, sulfur and magnesium are usually sufficient in Minnesota soils unless the soil is very sandy.

- Micronutrients are needed in small quantities: iron, manganese, molybdenum, chlorine, boron, copper, and zinc; these are also usually sufficient in Minnesota soils.

- A soil test can tell you what nutrients your soil is lacking.

- Organic matter such as compost can be a source of macronutrients like nitrogen, as well as micronutrients such as manganese and zinc.

Provide air and water

Plant roots and microbes need access to varying amounts of air and water for optimum growth. Fortunately, soil is full of microenvironments—tiny habitats that differ in the amount of available air, water and nutrients.

Soil compaction and disturbance such as excessive tillage can eliminate these important microenvironments. This makes it hard for plant roots to penetrate the soil, absorb water and nutrients, and interact with beneficial microbes.

Disturbing soil also disturbs weed seeds, exposing them to light and increasing germination—in other words, more weeds!

To minimize compaction and provide an optimal growing environment:

- Use designated walking paths through planting beds to avoid compacting soil around plant roots. Some design options include:

- Plant in raised beds.

- Beds no wider than 4 feet that allow you to reach across.

- Free-standing beds with access on all sides.

- To reduce or eliminate tilling consider using hand tools to prepare garden beds.

- Incorporate compost into compacted soil to increase air, water and nutrients for plants.

- Flowers and vegetables: incorporate 1 to 2 inches of compost 6 to 8 inches deep.

- Before planting trees and shrubs, incorporate 4 inches of compost 12 inches deep.

Keep it covered

The top few inches of soil contain an abundance of microorganisms, organic matter and soil nutrients.

Mulch or cover crops can be used to protect valuable topsoil from erosion and to add rich organic matter as they decompose.

- Raindrops landing on bare soil can splash soil particles several feet into the air.

- Mulching bare soil around plants prevents the splashing of soil particles and soil-borne pathogens onto leaves and stems, reducing the occurrence of disease.

- Mulch and cover crops conserve soil moisture, minimize weeds, and reduce plant stress by moderating soil temperatures.

Minimize chemical use

Pesticides kill pests, but they also can kill beneficial soil microbes and insects.

Before reaching for a chemical:

- Always consider alternatives to pesticides first, and low-impact pesticides like horticultural oils, insecticidal soap, spinosad, and Bt (Bacillus thurgiensis)

- Choose disease-resistant plant varieties and plants that will grow well on your site.

- Hand-pick larger bugs, such as Japanese beetles, from plants, and drop them in soapy water to kill them.

- Use a blast of water from your garden hose to knock insects off plants.

- Use physical barriers like row covers, bags on apples, or fences to keep out larger critters.

- Plant damage from insects and diseases is often cosmetic and not necessarily life-threatening. Visit the What's wrong with my plant tool to find out what diseases or insects may be affecting your plants and how to best treat them.

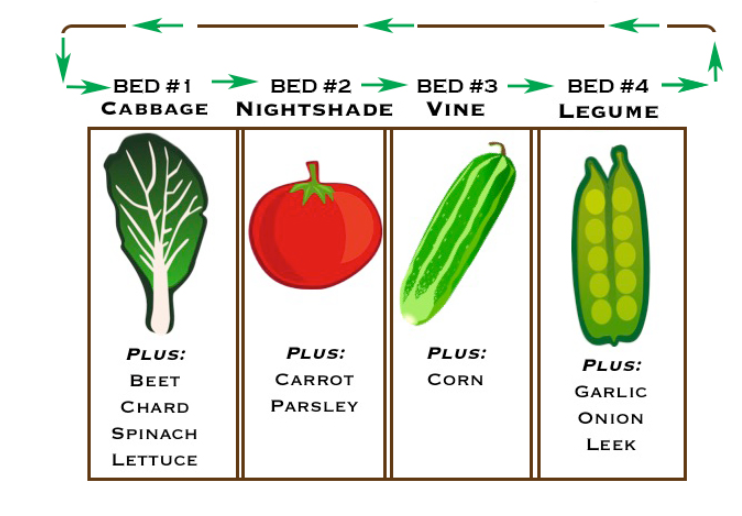

Rotate crops

While most microbes are beneficial to plants, disease-causing microbes may overwinter in soil and plant litter. These pathogens prefer to infest and feed on certain plants. Planting the same crop in the same soil year after year can increase diseases.

Rotating your crops:

- Reduces disease-causing pathogens by eliminating their food source.

- Prevents nutrient depletion.

- Plants with long roots, like carrots, absorb nutrients deeper in the soil.

- Shallow-rooted onions absorb nutrients in the top few inches of soil.

- Legumes, such as beans and peas, add nutrients back into soil.

- Add nitrogen to the soil by forming a mutual relationship with rhizobia, root-inhabiting bacteria that take nitrogen from the air and convert it into a plant-available form.

- When the legumes die, the nitrogen then becomes available to other plants in the rotation.

Rotation guidelines

Crop rotation is usually based on plant families. Plants in the same family are often susceptible to similar pests and diseases and tend to have comparable nutrient and cultural requirements.

For example, rotate crops from the cabbage family with crops from the sunflower family, or rotate crops from the squash family with crops from the grass family.

Other families, such as carrot or goosefoot, can be used to fill in the rotation wherever necessary.

If you don’t have the planting space to rotate crops, combine different plant families so that there is a diversity of crops in your vegetable garden.

Plant families

- Carrot family (Apiaceae): carrot, parsnip, parsley, celery, celeriac, dill, chervil, cilantro, fennel

- Sunflower family (Asteraceae): sunflower, lettuce, endive, escarole, Jerusalem artichoke, artichoke, chamomile, tarragon, echinacea

- Cabbage family (Brassicaceae): cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, kohlrabi, turnip, radish, kale, collards, rutabaga, watercress, horseradish

- Goosefoot family (Chenopodiaceae): beet, chard, spinach

- Gourd family (Cucurbitaceae): cucumber, melon, summer squash, winter squash, pumpkin, gourd

- Legume family (Fabaceae): bean, pea, cowpea, lentil

- Mint family (Lamiaceae): basil, lavender, marjoram, oregano, rosemary, sage, thyme, mint

- Onion family (Liliaceae): onion, scallion, garlic, leek, shallot, chive, asparagus

- Grass family (Poaceae): corn, sorghum, wheat, oats, barley

- Nightshade family (Solanaceae): potato, tomato, tomatillo, pepper (hot and sweet), eggplant

Reviewed in 2024