An anniversary provides both a look back at an organization’s accomplishments and a look ahead to its future. The 115th anniversary of Extension provides a wonderful opportunity to tell the story of Extension and why it matters.

Follow along, decade by decade, from the events leading up to Extension's beginnings and through early history to the early 2020s.

History by decade

Extension timeline

Read Extension's chronological history

Hatch Act funds agricultural research

The purpose of the Hatch Act, approved 1887, is to conduct agricultural research programs at State Agricultural Experiment Stations in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. insular areas, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. There are also other revisions and sections of the Act that are not as relevant to Extension.

The bill was named for Congressman William Hatch, who chaired the House Committee of Agriculture. The Hatch Act was a foundation for Extension at the time of the Smith-Lever Act of 1914.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture says, "Hatch activities are broad and includes research on all aspects of agriculture, including soil and water conservation and use; plant and animal production, protection, and health; processing, distribution, safety, marketing, and utilization of food and agricultural products; forestry, including range management and range products; multiple use of forest rangelands, and urban forestry; aquaculture; home economics and family life; human nutrition; rural and community development; sustainable agriculture; molecular biology; and biotechnology. Research may be conducted on problems of local, state, regional, or national concern."

Morrill Act creates land-grant universities and colleges

The original Morrill Act allowed for the creation of land grant colleges and universities. It was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 2, 1862.

States were given federal land, the sale of which was used to fund public colleges “that will promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes.” The effect is to expand higher education beyond the privileged few, educating many people to be productive citizens and members of the workforce.

Early 4-H projects include seed corn contests

Growing seed corn and baking bread were the first statewide 4-H club projects. In 1904, T.A. Erickson, then Douglas County school superintendent, organized seed corn contests for local boys and girls clubs. The aim was to educate youth (and their parents) about raising better corn. Seeking wider involvement, Erickson organized Minnesota's first county school fair, at Nelson School in Alexandria. Project exhibits included corn, potatoes and poultry.

Erickson, who became Extension's first state 4-H leader, wrote 4-H's founding principles: to interest youngsters in county life, to teach kids and adults at the same time, and to help the schools "teach boys and girls how to do things worth while."

Extension established at University of Minnesota

In 1909, an act was created to maintain a division of agriculture extension and home education in the department of agriculture of the University of Minnesota. It was proposed by Joseph Hackney, a St. Paul dairy farmer and legislator.

The first joint committee appointed to oversee the relationship between Extension and previous University outreach "farmers institutes" was made up of Cyrus Northrop, University president; Samuel B. Green, president of the farmers institute board and a College of Agriculture faculty member; and A.E. Rice of Willmar, chairman of the agricultural committee of the Board of Regents.

In 1910, A.D. Wilson was appointed superintendent of Extension. For the first two years of Extension, one-day workshops continued similarly to the previous farmers institute activities. By 1911, Wilson enlisted faculty to travel, using seven trains, across Minnesota to enable them to reach a large part of the growing areas of the state in a short time. Soon, more topics besides agriculture were added, including topics of interest to women and families.

Source: Helping People Help Themselves: Agricultural Extension in Minnesota, Roland H. Abraham

Smith-Lever Act establishes Cooperative Extension federally

The Smith-Lever Act of 1914 established the Cooperative Extension Service and provided federal funds for Cooperative Extension activities. The act required that states provide a 100% match from non-federal resources.

University of Minnesota and some other states were ahead of the curve, seeing the need to provide value to all residents of the state through educational outreach. Extension was established in Minnesota in 1909.

St. Paul hosts first junior livestock show

A state 4-H livestock show was the brainchild of Extension livestock specialist W.A. McKerrow. Supported by the Minnesota Livestock Breeders Association and the St. Paul meatpacking firms, and with rules set up by the boys and girls club staff at University Farm, the show was held at the South St. Paul stockyards in December 1918.

The first show produced 31 only "rather plain beef calves," but the idea caught on and became a major 4-H event. Most valuable, the program gave agents a way to build trust with parents by teaching their children how to manage their livestock.

President Wilson calls for food to 'win the war'

With world food supplies desperately low in 1916, Extension agents worked closely with farmers to aid the war effort. As the United States entered World War I, President Wilson provided $4.3 million to national Extension under the Emergency Food Production Act. County agents responded to the call, "Food will win the war," by teaching people to grow and preserve more food and change cooking and eating habits. Home economists traveled out to the people around the state, teaching canning classes and providing recipes for meatless and wheatless meals. This was Extension's first response to a major emergency and a trademark of its mission.

Hog cholera hits western Minnesota

A disastrous hog cholera epidemic in 1913 threatened the swine industry in Minnesota's west central counties. Renville County Extension agent W.E. Morris helped save hog producers close to $1 million. Renville County cholera losses dropped from 56 percent in 1913 to less than 5 percent in 1914, and Minnesota set a nationwide record in controlling the disease.

Morris organized a team of swine raisers in each township to help inform their neighbors and help veterinarians. In 1923, the legislature asked Extension to set up hog cholera vaccination schools led by Extension veterinarians. The veterinarians also taught improved herd management, and by 1972 the disease had been eliminated from the state.

Women pioneers lead way in home economics

As early as 1911, rural schools had hot lunch programs, thanks to Mary Bull, Extension's first state home economics leader. Before World War I, Minnesota's home economics staff grew by only four. But in 1917, with U.S. Department of Agriculture funding, Extension added 11 home demonstration agents. They expanded their reach through judging county fair exhibits, demonstrating baking and canning, and holding short courses at farmers' institutes. Specialists backed them up with popular leaflets on milk, fish, eggs, conservation, textiles and recreation. These Extension learning circles developed a foundation for many ways that Extension works today to help families use their resources wisely, from food and nutrition to family finances.

First milk cooperatives assist dairy farmers

In 1915, dairy farmers in the Twin Cities area were struggling to get fair prices from milk dealers. In 1916, four Extension county agents, led by Hennepin County agent K.A. Kirkpatrick, helped form the Twin City Milk Producers Association, a marketing cooperative. Kirkpatrick became the general manager and held the post for many years.

In 1917, the cooperative was attacked for "the offense of representing farmers" to sell their milk collectively, but in two years, the association was accepted. Extension went on to help organize two other cooperatives now known (and still thriving) as the Central Livestock Association and Land O' Lakes, Inc.

4-H grows out of first boys and girls clubs

Minnesota's 4-H clubs grew out of the boys and girls clubs in the early 1900s. The first 4-H symbol, in 1907, was a three-leaf clover, for head, heart and hands. The fourth leaf was added in 1911 to symbolize health (resistance to disease, enjoyment of life and efficiency). In 1914, the Smith-Lever Act brought 4-H into Extension nationwide. By the early 1920s, the clubs were known everywhere as "4-H clubs." By immersing kids in learning and leadership activities and instilling a healthy spirit of competition through project judging, 4-H contributed directly to the nation's leadership position in world agriculture and other industries.

4-H pledge comes of age

By the 1920s, 4-H club work appeared in every county's plan of work. In 1927, based on the term 4H-Club work and the fourfold concept of head, heart, hands and health, Extension adopted the well-known 4-H pledge.

Minnesota and Maine were the only states to add "my family" to their pledges. The only other change, in 1973, was the addition of "world" to the pledge.

I pledge my head to clearer thinking, my heart to greater loyalty, my hands to larger service, and my health to better living, for my family, my club, my community, and my country.

Drainage increases tillable farmland

The 1920s brought an increasing demand for tillable land. Stumps and boulders were a big problem and removing them was slow, difficult and expensive. Extension county agents taught farmers to use low-powered war surplus explosives on these and on constructing drainage channels on poorly drained flatlands.

In 1921, Extension had helped farmers in 22 northeastern Minnesota counties clear 35,000 acres of land, saving $70,000 above other removal costs. Many farmers remember that Extension helped their fathers and grandfathers drain wetlands to grow more crops. Today, Minnesota ranks among the national leaders in both corn and soybean production.

Grasshoppers destroy Minnesota crops

Tough times in Minnesota in the 1930s brought economic depression, droughts, and clouds of grasshoppers that destroyed crops across the state. Extension entomologist H.L. Parten and county agents conducted grasshopper-baiting demonstrations with poison bait provided by state funds. In 1939, one-fourth of all Minnesota farmers spread the bait and avoided an estimated $12.6 million crop loss during a time of 40-cent-per-bushel corn. Extension's response to the grasshopper plague helped create a research-based approach that farmers, state officials and Extension would use to tackle future problems, such as the 1980s farm foreclosures and the 2007 bovine tuberculosis outbreaks.

Minnesota farmers become acquainted with soybeans

As early as 1937, southern Minnesota farmers were experimenting with soybeans as a new oil crop. Extension tried to hold off promoting this until it was clear whether it was really marketable. The farmers insisted, however, and Extension listened. By the 1940s, soybean variety demonstrations were among Extension's regular agricultural programs. University soybean geneticist Jean Lambert developed new varieties that made Minnesota a leading soybean state. Extension introduced the varieties to farmers through field days, publications and the mass media. Farm income from soybean production alone was huge, more than the entire University budget in the 1950s.

4-H youth conservation programs take root

As early as 1926, 4-H participants were contributing to conservation and environmental work. The Conservation Leadership Camp at Itasca, begun in 1934, continued for 51 years. Each year, 200 youth learned firsthand about wildlife and land conservation. Taking their knowledge back to their hometowns, they planted thousands of trees, started windbreaks, built bird feeders and seeded forest tree nurseries. The seedlings the early campers planted in Itasca State Park are now towering red pines that park visitors still enjoy. 4-H environmental work goes on today in county camps and programs.

Electric cooperatives come to rural Minnesota

President Roosevelt established the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) in 1935, but the U.S. Department of Agriculture left it up to individual groups to organize. On their own, local groups asked Extension for help. Two months after REA went into effect, Meeker County Extension agent Ralph Wayne and former agent Frank Marshall organized the first rural electric cooperative in Minnesota. This two-year work in progress became the first demonstration site in the nation.

In 1940, Extension sponsored nine farm and home equipment shows across the state showing how electricity could be used in operating farms and modernizing rural homes.

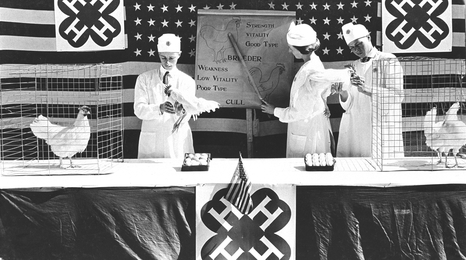

Marketing of agricultural goods reaches new levels

As World War II ended, farmers were concerned about how to effectively market the abundant crops they were producing. In 1946, the Research and Marketing Act gave funds to Extension nationally for marketing programs. Minnesota used its share to develop three projects: improving efficiency in marketing and distributing eggs and poultry, improving market quality of milk, and developing and marketing frozen foods. In 1950, Extension added a consumer marketing project to let people know where they could find plentiful food supplies. This helped producers get a better price for their products. Consumer marketing specialist Eleanor Loomis used radio and television to broadcast Extension information.

Mattress-making provides dual solutions

After the Great Depression of the 1930s, many rural and low-income people were sleeping on cornhusk mattresses. In 1941, the U.S. Department of Agriculture had a large amount of surplus cotton, bought up from Southern cotton producers. Extension agents in 84 counties accepted the offer of cotton and ticking and organized mattress-making centers in village halls and county fair buildings. They helped 70,000 Minnesota families make their own mattresses and comforters. Total cost of supplies was 88 cents per mattress and 33 cents per comforter. With this program, Extension helped solve an economic problem in one part of the country and assist low- income farm families at home.

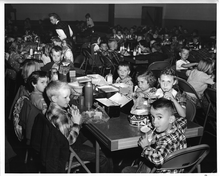

Hot lunch programs become new norm

In 1935, a St. Louis County home demonstration agent predicted that schools would serve hot lunches just as they hired teachers and bought books. As early as 1911, Extension had set up a hot lunch program in the rural schools, complete with bulletins and recipes.

By 1940, hot lunch programs had been established in more than 200 Minnesota schools. In the 1940s and '50s, Extension nutritionists taught school lunch staff around the state how to transform surplus commodities into healthful meals.

Programs reach American Indian communities

Extension expanded its health and nutrition programs in the mid- 1950s to American Indian families. Invited by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to set up programs on the White Earth and Red Lake reservations, Extension hired its first agents to work with those communities. These agents became known and trusted on the reservations. They organized 4-H clubs and homemaker groups and taught gardening, nutrition and clothing projects. This work laid the foundation for programs such as the White Earth Math and Science Academy in the 1990s and ongoing interactive nutrition programs that help increase understanding today between Minnesota's oldest and newest cultures.

New ways of reaching families gain popularity

During the post-war 1950s and '60s, women wanted to know more about family life, mental health, farm policy, farm business and improving their homes. Extension responded with new programs and in 1958, using a new way of communicating, began broadcasting best food buys over Minnesota's 22 TV stations. Heart disease among women was a big concern, and Extension taught lessons in eating right to manage weight. Extension also developed nationally known programs to teach handicapped homemakers how to manage with less energy or limited motion. Now more than ever, families relied on Extension's research- based information to help them make good decisions.

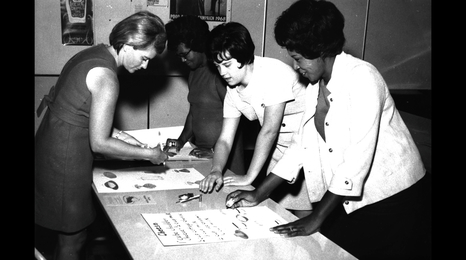

EFNEP reaches low income families

Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) is one of the oldest nutrition education programs in the United States. EFNEP was started by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1968 and operates in all 50 states and some territories. EFNEP started out using a home visit one-on-one model, which has largely been discontinued.

Today, EFNEP provides an experiential learning experience — there are often good smells coming from an EFNEP classroom. What’s more, participants acquire the knowledge and skills to make behavior changes aimed at improving their family’s diet and well-being. Additionally, participants learn how to incorporate more physical activity into everyday living. CNEs teach in a variety of settings, such as food shelves, schools, income-based housing complexes, and community centers. Classes are taught in a variety of languages throughout Hennepin, Ramsey, Anoka and Dakota counties.

Minnesota is also known for being a relatively innovative state. In 1979, it was one a small group of states that piloted EFNEP education for individuals and families receiving food stamps. Guess what that program is now called? If you guessed SNAP-Ed, you would be right! University of Minnesota Extension offers both EFNEP and SNAP-Ed programming, both of which have similar goals. Here are some parallels between EFNEP and SNAP-Ed:

- Both programs serve limited income audiences.

- Both programs deliver nutrition education through a series of classes.

- Both programs serve diverse populations. At least 72 percent of all EFNEP adults are people of color.

So what are the differences?

- EFNEP uses a peer paraprofessional model to educate and connect with their audience. I

- EFNEP CNEs are able to leverage the insight and knowledge of their communities to establish relationships with a single agency to set up classes.

- EFNEP uses both pre- and post-participant 24-hour dietary recalls and behavior checklists.

Volunteer 4-H leaders attend first national forum

In 1960, the first nationwide forum for volunteer 4-H leaders was held at the National 4-H Center in Washington, D.C. Adult volunteers play a critical role in 4-H's unique learn-by-doing model. They guide kids through a discovery process by getting them to question, analyze and reflect. They are trained in the important "keys to youth development" and they make sure youngsters feel a sense of belonging.

Today, more than 11,000 Minnesota volunteers contribute 92,700 hours annually. That's a contribution worth more than $21 million each year. But volunteers' greatest value is the incalculable contributions they make to the lives of young people.

New programs boost Minnesota tourism owners

Extension's first tourism programs were developed in the 1960s for resort owners in northeastern Minnesota. Tourism specialists used the tried-and-true Extension model for working with farmers and small communities. They helped community leaders plan and develop tourism while boosting business activity, respecting the interests of local citizens and protecting natural resources. The programs spread as community development educators provided research and educational programs across the state. Throughout, the Minnesota Department of Tourism provided feedback and support. In 1987, Extension and the University of Minnesota, with private endowments, created the Tourism Center for ongoing educational programs.

Message spreads about safe chemical use

In the 1960s, Minnesotans became concerned about the safe use of chemicals. Farmers used pesticides to control weeds, insects and plant diseases. Using additives in animal feeds to encourage growth and promote animal health was another concern. And a big worry was the direct hazards to people who applied chemicals. In 1964, Extension pulled together a committee of entomologists, agronomists, plant pathologists, animal scientists, nutritionists and others to gather research and set up educational workshops. Working in concert with state agencies and industry groups, Extension presented courses across the state for chemical applicators, farmers, pesticide dealers and others responsible for safe environmental practices and a safe food supply.

Anoka County holds first 'Field Days'

In Anoka County in 1965, Extension organized a new program that took elementary school teachers and their students outdoors to learn about Minnesota's natural resources. Extension faculty taught 2,000 kids at natural camp settings. The workshops, outdoor lab sessions and field trips all offered a new kind of experience that laid the foundation for today's environmental science field days. Now, Extension offers innovative classes across the state for nature center educators, teachers and youth environmental educators (like those who work with 4-H and Scouts groups). Today, Extension environmental science education programs offer curriculum tips, research-based best practices and ready-to-teach content.

Master Gardener program enlists volunteers

From showing kids how to grow vegetables to teaching homeowners about composting, Extension's Master Gardeners have served thousands of Minnesotans every year since the program began in 1977. Master Gardeners are volunteers trained by Extension professionals to share their knowledge in their communities.

In 2018, 2,400 Master Gardeners across Minnesota contributed 145,134 hours to volunteer service. The program has expanded from its early days of answering home gardener questions. Today's Master Gardeners help develop schoolyard garden plans, combat invasive species in lakes, involve kids in plant science programs, work with organizations like Habitat for Humanity, and help new Americans work together in community gardens.

Mark Seeley brings knowledge about weather, climate to all of Minnesota

It was the drought of the late `70s that prompted the Minnesota state legislature to fund a climatology position at the University of Minnesota. After a brief period working for NASA, Mark Seeley was recruited to the University in 1978 and worked as an Extension climatologist and a professor until his retirement in 2018.

The goal of the position was to translate information to make it useful for making decisions about farming and soil and water conservation. He worked closely with the National Weather Service, the Minnesota State Climatology Office and other state agencies.

A recognized voice, Seeley has appeared on Minnesota Public Radio since 1992 and is a frequent guest on tpt’s Almanac. His weekly newsletter Minnesota WeatherTalk reaches thousands. Seeley wrote the Minnesota Weather Almanac, published by the Minnesota Historical Society Press, and also co-authored Voyageur Skies with photographer Don Breneman.

Seeley is long-known as a climatologist of the people. He regularly traveled to all 87 Minnesota counties to talk with Minnesotans about weather, and how communities can adapt to climate change.

International roots grow with Minnesota Project and Morocco

Nearly 400 Moroccans earned degrees through the 1970s-era Minnesota Project, and many maintain relationships with Minnesota researchers and businesses today.

Extension's global work began with supporting agricultural exports during and after World War I. In the '60s and '70s, a relationship started with Morocco. The "Minnesota Project" educated Moroccans, who then returned to Morocco to create a world-class research and teaching institute.

Many of those college students became leaders, such as Mohammed Sadiki, secretary general in Morocco's Ministry of Agriculture. "That project trained 400 'ambassadors' for Minnesota, who are now living in Morocco," he says. "To this day, they hold Minnesota—and the U.S.—in their hearts."

Hmong farmers begin growing, marketing in Minnesota

In the late 1970s, after the United States withdrew from the Southeast Asian conflict, more than 10,500 Southeast Asian refugee families settled in the Twin Cities area. In 1983, Extension launched an intensive program to help these families support themselves by growing, processing and marketing vegetables. After four years of training and Extension's help in setting up an agricultural business cooperative, Hmong farmers set off on their own.

Today, many people of Southeast Asian descent sell produce through Minnesota's agricultural specialty markets and farmers markets. Extension's early work with banks, businesses, agencies and communities also created the current network of resources for Hmong and other immigrant farmers across Minnesota.

Concept of low-maintenance lawns catches on

"Don't bag it," the catchphrase for leaving grass clippings on your lawn, was coined in the 1980s by Extension horticulturists and horticultural educators such as Bob Mugaas. Since then, Extension educators have taught thousands of Minnesotans to "green up" their lawns with fewer pesticides, less water and less work. Decades of turfgrass research by University agronomists backs up Extension's information. Lawn-service businesses and the government benefit, as well. An added bonus is research-based information about composting. Thanks to Extension, Minnesotans are making more informed choices and protecting other natural resources such as lakes and streams by caring responsibly for their lawns and green spaces.

Farm crisis hits Minnesota producers

In the 1980s, a devastating financial crisis forced thousands of Minnesota farmers into bankruptcy and foreclosure. Family ties also unraveled under deteriorating financial situations. In 1984, Extension agricultural economists developed farm financial software (FINPACK) to help farmers analyze their businesses, and educators trained more than 33,000 people to help families reduce stress and manage their resources. In 1986, Extension developed a state- requested farmer-lender mediation program to facilitate discussions about credit problems. By the early 1990s, Extension had worked with 85 of Minnesota's 87 counties. Since then, FINPACK has been used by tens of thousands of farmers nationwide.

Invasive species education moves to the forefront

Extension has always worked to manage invasive species in agriculture. But in the late 1980s, Extension also led the way in addressing threats to Minnesota's water recreation and economy from aquatic invasive species. Educators moved fast to get information out to the public about zebra mussels, which can clog pipes and cost millions of dollars for clean-up. Educators also helped Minnesotans curtail other major threats--purple loosestrife, Eurasian water milfoil, curly leaf pondweed--saving the state from untold numbers of dollars in clean-up and landowners from heavy loss to property values. Today, Extension educates about the benefits of prevention, containment and minimizing impacts to keep new species from spreading.

Regional Sustainable Development Partnerships

In 1997, the Minnesota Legislature established the Regional Sustainable Development Partnerships (RSDP) to foster Greater Minnesota sustainability through a two-way flow of expertise and ideas between communities and the University. A part of University of Minnesota Extension since 2011, each year RSDP supports approximately 125 community-based projects in the areas of sustainable agriculture and food systems, clean energy, natural resources, sustainable tourism and resilient communities.

Examples of Extension RSDP and community success stories are in the areas of:

-

Pioneering local foods issues

-

Advancing clean energy

-

Fostering rural grocery resilience

-

Supporting sustainable communities

-

Protecting our natural resources

-

Bolstering small-scale farming

-

Building supply chains

The voluntary work of dedicated community leaders with a passion for sustainability helps drive this work. RSDP board and work group members contribute approximately 7,500 hours in volunteer time each year.

The statewide office for the Clean Energy Resource Teams (CERTs) is part of RSDP. CERTs provides individuals and their communities the resources they need to identify and implement community-based clean energy projects. They empower communities and their members to adopt energy conservation, energy efficiency, and renewable energy technologies and practices for their homes, businesses, and local institutions.

Families turn to Extension when disaster strikes

Minnesotans have long relied on Extension in times of disaster. When the St. Peter tornado and the floods of 1997 struck, for example, Extension educators were there in the communities, helping residents pick up the pieces. Ready with research-based information, Extension showed people how to dry out their homes and belongings, prevent mold and keep their food from spoiling. People also called on Extension to help them deal with insurance, cope with stress and address tough financial questions. From pulling together the agencies needed to helping with long-term recovery, Extension educators are prepared to help people get their lives and communities back on track.

Extension acts on education needs for divorcing parents and other families in transition

In 1994, a group of local University of Minnesota Extension educators in Winona County noticed an increasing need for education for parents experiencing divorce. They drafted a curriculum that would later become Parents Forever and piloted it in the surrounding communities.

In 1996, the Minnesota state legislature requested that the Minnesota Supreme Court form a committee to examine visitation and custody issues. The committee concluded that parent education during the divorce process could help minimize return-to-court appearances. The committee’s recommendations were written into statute. In court cases when custody or parenting time is contested, the parents of minor child are court-ordered to attend a parent education course. The Minnesota Supreme Court and/or district judges approve these parent education courses and ensure that they meet the 25 minimum standards defined in the policy.

In response to this new mandate, Extension revised the existing parent education curriculum and launched Parents Forever in the fall of 1998. Since that time, Extension trained hundreds of professionals across Minnesota and beyond how to start and sustain a Parents Forever program in their county.

“Bridging” leadership programs are born in Brown County

A convergence of events and conversations told Katie Rasmussen, University of Minnesota Extension educator, that “something wasn’t working” among the towns in Brown County. The events included 1998 tornado response and recovery, a county fair board issue, and businesses in one town feeling like they weren’t part of the wider region’s business and advertising efforts. Rasmussen convened an informal meeting of involved individuals to discuss those issues and an east/west and urban/rural divide within the county.

The group envisioned a different future and decided to share their vision with others. They recruited, offered workshops and developed a program that would create bridges across the towns. Rasmussen assisted the volunteer leaders to start the first “bridging” leadership program, Bridging Brown County. It is a nonprofit organization that strengthens the community by bridging relationships of understanding and communication. Bridging Brown County has a leadership program designed to help current and emerging leaders understand the dynamics of the community and the role leadership shares in building healthy communities.

Others nearby noticed the success and the bridging model of leadership education has since spread to McLeod, Nicollet, Kandiyohi, Sibley and Redwood counties.

Carver County Dairy Expo begins its long tradition

The daylong Carver County Dairy Expo is known for its educational programming, trade show and networking opportunities. Each year is a reunion of sorts for the industry to gather, learn and network.

Retired Extension educator Vern Oraskovich says about the 1992 origin of the Dairy Expo, “There was a group of us (Minnesota Dairy Initiative), who met with dairy farmers as a team to help them become better producers; we looked for ways to address herd health, nutrition, production and profitability. We decided we could help more farmers if we had a program where more dairy producers could get information and learn about Extension research. So we hosted our first Carver County Dairy Expo.”

The event draws more than 300 people, representing more than 24,000 cows and 23 Minnesota counties.

Over the years, the Carver County Dairy Expo programs introduced production benchmarks and helped producers lower somatic cell count. Cow comfort, economics and technology have also been important. Sessions are now offered in Spanish, reaching more of the people who have the most day-to-day contact with cow care and milking.

“I feel honored to carry on this tradition,” said Colleen Carlson, Extension educator in Carver and Scott counties, who now leads the event planning. “There is a real feeling of camaraderie.”

“Who Gets Grandma’s Yellow Pie Plate?” helps families with inheritance decisions

In 1994, Extension educators across Minnesota were hearing about family members struggling with inheritance decisions, especially challenges regarding personal possessions (“non-titled property”). At that time, little was known about passing on personal possessions, the family dynamics involved, what works and what doesn’t, and effective planning and communication strategies for families.

A team of Extension faculty developed research-based, conceptually sound, trustworthy, and user-friendly educational resources, along with a multidisciplinary advisory group. The result is “Who Gets Grandma’s Yellow Pie Plate?” A range of resources, including a workbook, video, and workshop curricula, have been developed and revised over the years.

The title comes from the real-life family story of an Extension intern named Andrea. In her family, the item of difficulty for choosing a new owner was a ceramic yellow pie plate that had belonged to her great grandmother and then her grandmother. The tradition of baking and eating pies together had imbued it with value, and yet it’s not the type of item likely to appear in a person’s legal will. It's a working metaphor for the wealth of meaningful personal possessions that families want to pass on to future generations without creating conflict.

“Using Native Plants” satellite video program covers many settings

In 1996, a year-long collaboration of University of Minnesota Extension and University of Wisconsin Extension resulted in several videos presenting the “why” and “how” of native plants. Callers had questions answered live and received packets with plant lists and recommendations for growing native plants in the Eastern deciduous woodland, prairie, wetland or lakeshore areas, and in traditional garden settings.

This is one of the first programs to discuss how to use native plants in home landscapes, a topic studied throughout the career of Extension horticulturist Mary Hockenberry Meyer. Using Native Plants has been preserved in the UMN Digital Conservancy. The two-hour program is split here into four segments: Segment 1 includes the program introduction and Eastern Deciduous Woodlands, with expert Mary Lerman at the Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden. Segment 2 covers Prairie Establishment and Maintenance, with experts Ron Bowen, Evelyn Howell and Virginia Kline. Segment 3 covers Managing Wetlands with U of M professor Sue Galatowitsch. Segment 4 covers the topic of traditional gardens and native plants at the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum with horticulturist Mike Heger, owner of Ambergate Gardens, along with the conclusion of the program.

Meyer directed the Extension Master Gardener program from 1994 to 2007. Author of numerous Minnesota plant guides, she coordinated statewide multimedia educational programs in environmental, consumer and commercial horticulture, including sustainable home landscapes. She continues managing the grass collection at the Arboretum and writing about the Arboretum's historic plant collections. You can still hear her on WCCO's 8 a.m. Saturday morning Smart Gardens radio show.

Marla Spivak, Extension colleagues and volunteers help pollinators

Honey bees and wild bees pollinate more than 70 percent of our fruits and vegetables, but honeybees have been disappearing at alarming rates in recent years due to the combined effects of parasitic mites, diseases, lack of habitat and exposure to pesticides.

In 2007, when alarms began to sound about the state of bees, Extension Entomologist Marla Spivak’s bee lab came into the national spotlight. She and her students engage in research regarding bee health and encourage people to plant more flowers that attract pollinators. Flowers provide bees with critical nutrition—protein from pollen and carbohydrates from nectar.

Extension Master Gardeners disseminate information statewide about which native plants and flowers are best for bees and other pollinators, but Extension researchers also began to study the concept of using cover crops such as alfalfa to feed pollinators on farms. Many others in Extension, from crop educators to turfgrass scientists, worked with Spivak to help build awareness and find solutions.

In 2010 came the announcement of the MacArthur Fellowship, a “Genius Award” to Spivak for her work on all aspects of honey bee biology. Spivak was the first faculty member in 20 years at the University of Minnesota to receive this honor. The Extension Bee Squad helps beekeepers and the community in the Twin Cities promote the conservation, health and diversity of bee pollinators through research, education and hands-on mentorship.

Tourism owners learn benefits of 'green tourism'

In a state that depends heavily on natural resources for its tourism industry, it's vital that we protect and preserve our environment. That's why Extension tourism educators work to teach local communities how to practice sustainable tourism. Since 2006, the University of Minnesota Tourism Center has taught hundreds of tourism operators to "green up" their businesses with environmentally responsible practices like recycling, reusing, water conservation and energy audits. Both visitors and residents can enjoy quality experiences ranging from environmental adventure parks to family resorts that use sustainable landscaping or lakescaping techniques. And satisfied visitors can return home and tell stories that bring more friends and relatives to Minnesota.

Soybean aphids arrive in Minnesota

Extension is known for pulling together partnerships to tackle problems fast. In 2001, Extension educators discovered soybean aphids in Minnesota fields. Entomologists confirmed the outbreak and Extension quickly joined forces with Minnesota soybean growers and state and federal agencies. Together, they reduced economic losses by teaching farmers how to scout for aphids and when and how to control them. Within a year, Extension was using a sophisticated University of Minnesota computer model to combine weather information with agronomic and entomology expertise to guide growers. The model has since been adopted throughout the Upper Midwest and will help north central states save an estimated $1.3 billion over 15 years.

Number of obese school children reaches new heights

From 1976 to 2004, the percentage of overweight grade-school children in the United States nearly tripled, from 6.5 to 18.8 percent. In 2007, Extension nutrition experts and nutrition education assistants began piloting an activity-packed curriculum, "Go Wild with Fruits and Vegetables," in 22 Moorhead-area schools. The program uses stories, songs, games and "mystery food" taste tests to make the lessons fun, and is based on studies showing that children are more likely to believe and act upon a message if they hear it from multiple sources. So far, 3,600 grade-school children have learned that good food and physical activity are smart choices. The Go Wild curriculum went statewide in 2009-10.

Horizons brings hope to Minnesota communities

Extension's Horizons program helped small communities with high poverty rates develop their own leaders and create a thriving community. St. James was one of nine Minnesota communities to complete the program in 2008. With a boost from Extension and the Northwest Area Foundation, St. James factory workers, high-school students, business people, educators and civic leaders together shaped an exciting new future for their town.

The secret to success was a "grass roots, not top-down" approach and getting together everyone in the community to solve their own issues. In all, 36 Minnesota communities with populations under 10,000 and high poverty rates participated in Horizons. The model informed future programs offered by Extension to help communities create change.

Dedicated volunteers become Master Naturalists

Minnesotans tend to know a lot about birds and plants. But they may not know as much about water quality, geology or land issues. In 2005, Extension and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources created the Master Naturalist program to teach people about their environment and build a corps of dedicated, enthusiastic volunteers. Master Naturalists learn the natural history of one of Minnesota's three biomes: Big Woods, Big Rivers; Prairies and Potholes; or North Woods, Great Lakes. Then they perform nature-related service, like gathering prairie seed and helping educate others. In 2018, 892 Minnesotans were Master Naturalist volunteers.

Aquatic Invasive Species Detectors volunteer to keep lakes healthy

Minnesotans value water and want to keep our lakes healthy and free of invaders that crowd out native species. Since 2017, people who want to make a difference have been able to apply to volunteer as Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) Detectors.

The program is led by University of Minnesota Extension and the Minnesota Aquatic Invasive Species Research Center (MAISRC), in coordination with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Volunteers are trained to identify and report suspicious findings, and to help boaters understand how to prevent the spread of unwanted plants, fish and invertebrates.

With over 13 million acres of surface water in Minnesota, officials can’t examine all of it. They need as many eyes on the water as possible, and that’s where AIS Detectors have been able to fill the gaps. They have already discovered some species, like starry stonewort, in time for treatments to get invaders under control.

It’s also helpful when the people delivering the message in communities are in the same boat, proverbially speaking.

“People can tune out the message sometimes,” says Bill Grantges, Itasca County lake manager. “But when an AIS Detector comes, especially if they’re from the same chain of lakes, it’s like a family member is talking to you.”

The AIS Detectors program launched with a grant from the Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund, administered by the Legislative-Citizen Committee on Minnesota Resources.

4-H's unique approach teaches life skills in urban after-school settings

4-H's unique principle of engaging kids in something they like—"learning by doing"—helps them make better decisions, give back to their communities and grow up to be solid, contributing citizens.

In 2007, young people followed a traditional 4-H camp model to become "camp counselors" in after-school leadership groups, such as Urban Youth Lead. Minnesota 4-H in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area began Urban Youth Lead in 2006. Projects are designed by the participants themselves and can include job shadowing, volunteering, service work and academic mentoring.

In 4-H style, the youth learned record-keeping skills and created portfolios of their learning experiences and growth.

Newcomers mean “brain gain” for rural Minnesota

The perception of rural America is often one of stagnation and decline: High school graduates flee their small towns for college or to jump-start exciting careers, never to return. Despite the loss of the 20-somethings, Extension research fellow Ben Winchester didn’t see doom and gloom for rural America. By 2011 he had the research data to uncover another rural migration trend: growth among 30- to 44-year-olds. He called this addition of middle-agers, who bring with them educational achievements and established earning power, the “brain gain.”

Winchester published studies about the trend and led research to learn more about these new rural residents. He and his colleagues in Extension’s Department of Community Development have helped community leaders reach out to newcomers and focus on becoming a place to move to rather than worry about young people moving away.

Extension research about the rural “brain gain” has inspired resident recruitment efforts throughout the state.

Extension 4-H partners with Ka Joog to reach Somali-American youth

Education is regarded highly in the Somali-American community. In 2014, a new partnership began connecting Somali youth to Extension 4-H and the University. Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) programs were the first 4-H programs delivered with Ka Joog, a nonprofit on the West Bank in Minneapolis, which served approximately 2,500 Somali youth annually at the time.

In Somali, Ka Joog means ‘resist’ (literally, ‘stay away’) which symbolizes the goal to help Somali youth resist drugs, violence and other negative influences and help them stay on the path to higher education. “Ka Joog began with a vision, a dream and a lot of what-ifs,” says Mohamed Farah, Ka Joog executive director and 4-H program coordinator. “Our partnership with Extension 4-H and the University is a perfect fit.”

Extension in Minnesota has helped other states learn from these experiences with refugee youth and families. “Minnesota is home to a unique opportunity for cultural learning,” says Jennifer Skuza, Extension associate dean for youth development. “Youth work has long been a venue for culture learning and for creating positive social change.”

Minnesota youth conduct research through the 4-H Science of Agriculture Challenge

The U.S. faces a shortage of scientists and professionals that can meet needs in jobs and business. The first program of its kind in the country, the 4-H Science of Agriculture Challenge began in 2015 with the goal of igniting excitement about agriculture, increasing ag science literacy and expanding the pipeline of youth pursuing agriculture-related careers.

Youth teams conduct research on areas of interest, from bees to biodiesel to breeding livestock. Each team has an expert adult mentor to guide them. Teams present their results at two-day events on the University of Minnesota campus, where they improve their skills in talking to others about their projects, experience being judged by those working in agriculture and have an opportunity to win a scholarship.

Thanks to support from the Minnesota Corn Growers and many other groups and individuals, the experience and learning have improved for youth each year.

Cottage to table: Local food producers make it their business to prevent foodborne illness

Under an exemption in Minnesota's 2015 cottage food law, Minnesotans can make and sell certain types of food from their home kitchens (or "cottage") without a license as long as they register annually and complete food safety training. They produce confections, canned jams and jellies, salsa and sauces, and more.

Suzanne Driessen, Extension food safety educator, and her colleagues, got to work developing training by talking with cottage food producers about their educational needs. The resulting workshops focus on processes like drying, baking, canning and fermenting, as well as packaging, labeling, storing and transporting a safe food product.

Students bring in their own products to test pH and moisture content—key hazard markers. Stations set up around the classroom allow learners to choose hands-on, interactive lessons about what’s most relevant to their type of food product. The Cottage Foods Course is now also offered online.

"It's beneficial to me to be able to stay home and make some side income for my family," says Karen Peterson, who sells baked goods like salted caramel cupcakes out of her home. At the inception of the new law producers like Peterson could earn up to $18,000 annually from cottage food sales.

Avian influenza brings losses, Extension response to Minnesota turkey farms

In 2015, losses in poultry production and related businesses due to an avian influenza outbreak were estimated at $650 million in Greater Minnesota. Carol Cardona and Sally Noll, Extension poultry specialists, conducted research on biosecurity approaches and diagnostics to help poultry producers prevent such losses in the future.

One biosecurity upgrade recently in use across many turkey facilities in Minnesota is the "Danish entry system." The system clearly assigns clean areas to the entry area of a barn and demarcates areas for clothing and footwear changes. Upgrades to the system—including additional walls and washing facilities—may further reduce risks. Noll and Cardona worked with Extension engineers on improvements to the Danish entry system, while comparing efficacy and costs. In 2012, Cardona had developed a diagnostic test for detecting influenza in water samples that she rolled out to producers, helping them to catch the disease early and prevent spread.

This work led to an expansion of Extension's work in farm biosecurity. Today, a Biosecure Entry Education Trailer brings hands-on teaching and learning experiences anywhere in Minnesota, including with youth and labor audiences working with a variety of livestock.

SuperShelf transforms food shelves

With more than half of Americans reportedly living paycheck to paycheck, one rent hike or car repair bill can force anyone into food insecurity.

Replacing food insecurity stigma with the respect and dignity that grocery store shoppers take for granted is the primary goal of the SuperShelf program, a multipronged effort by U of M Extension and partner organizations around the state. The program certifies a food shelf as a SuperShelf after a consultant from U of M Extension’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed) walks them through a process to prioritize healthy, appealing food; reimagine their layout; and create legible signage in multiple languages.

As of early 2024, the SuperShelf program had certified 57 Minnesota food shelves, with 30 more en route to final certification.

Coping and learning through Covid-19 pandemic stress

The COVID-19 Pandemic changed Extension education, increasing online offerings, while keeping participants engaged in learning and learning new technology.

4-H animal showcases, for example, were often conducted from home, with youth creating videos and participating in virtual judging. Extension educators working in health and nutrition, family resilience and horticulture responded with creative, thoughtful solutions that took into consideration food insecurity, and physical and mental health challenges presented by the pandemic, as well as by the 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

Extension Regional Sustainable Development Partnerships collaborated with rural grocers to deploy meal kits to community members who needed to isolate themselves. Extension worked with the Minnesota Pork Board and others to provide nearly 12,300 pounds of ground pork to Second Harvest Heartland.

In-person education continued outdoors, and by late 2021, indoor and outdoor events were back. Hybrid education was developed, with safe and effective education that respected everyone's choices.

Extension participants communicate about climate

The University of Minnesota Climate Adaptation Partnership, founded in 2008 by Extension and the College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences, directed since 2021 by Extension Climate Scientist Heidi Roop, developed a community-based climate communicators program.

In 2021, the first program group of 20 participants came together to build their knowledge of local climate impacts and the skills and confidence to discuss climate change in their communities. Participants, seeing the gap between the knowledge that climate change is real and talking about it, connected with scientists and communication experts. They identified opportunities to apply their new climate communication skills, created family-friendly events, met with elected officials and worked with municipal leaders on local adaptation actions.

Future shines bright for solar schools

Solar for Schools, a $16 million grant program for school solar energy projects was set into place by the 2021 Minnesota Legislature. With dropping prices, innovative financing and a growing commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the program created a “magic moment” for solar school projects in Minnesota.

Extension staff played a key role. The Clean Energy Resource Teams (CERTs), a partnership that includes Extension’s Regional Sustainable Development Partnerships, served as technical advisers to participating districts, helping them assess their readiness and connect to needed resources. While the savings free up more money for education, the installations also provided STEM learning opportunities for students.

The role was a natural for Extension, which has a longstanding commitment to renewable energy, community development and strengthening rural economies.