Bacterial leaf streak (BLS), also known as black chaff, is a disease of wheat, barley, triticale, oats and many other cool- and warm-season grasses (Figure 1). BLS is more prevalent with warm, humid weather.

Impact on farmers

Severe outbreaks are commonly associated with weather incidents that damage leaf tissue. The disease can be found across the globe and, although not new to the region, has become more prominent in Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota since 2008.

The disease’s impact on grain yield and quality isn’t well-documented. However, yield losses up to 40 percent have been reported.

Unlike many fungal pathogens, BLS is a sporadic disease, occurring in some fields but not others. Even within a field, symptoms can be very patchy; some areas can appear severely affected, while immediately adjacent areas are completely devoid of symptoms.

About bacterial leaf streak (BLS)

BLS is caused by the bacterium Xanthomonas translucens. Two common types of this pathogen that can infect wheat and barley are currently recognized. These differ in pathogenicity, and are therefore referred to as pathovars:

-

Xanthomonas translucens pv. undulosa is pathogenic on wheat, barley, triticale and other grasses.

-

Xanthomonas translucens pv. translucens is specifically pathogenic on barley.

Research efforts are in progress to more clearly delineate the pathovars associated with recent disease outbreaks in Minnesota. BLS infection initially becomes present as water-soaked lesions on leaves, with advanced infections developing black chaff symptoms on glumes (Figure 2).

Distinguishing from bacterial leaf blight (BLB)

BLS infection caused by Xanthomonas translucens shouldn’t be confused with bacterial leaf blight (BLB) caused by Pseudomonas syringae. BLB isn’t commonly found in Minnesota, and causes spotty and blotchy leaf lesions rather than the streaked lesions of BLS.

BLS symptoms generally appear during the grain-fill period.

Symptoms

Earlier in the day, look for dark brown, water-soaked streaks on the leaves (Figure 1, part B). You may find milky droplets of bacterial exudate on the lesions (Figure 1, part A). This ooze will dry up and form a scale-like glaze (Figure 1, part B).

If you hold your fingers against the leaf’s underside or hold the leaf up to the light, the lesions may appear transparent, especially when the leaf surface is wet. Symptoms of black chaff include brown-black discolorations of glumes (Figure 2).

Glumes may also be discolored at the base and, at times, you can see banding. You may also find bacterial exudate on the glumes.

Distinguishing from pseudo black chaff

This exudate is one way to distinguish BLS from a brown, black or purple discoloration of the glumes (melanosis) that’s associated with a genetic syndrome called pseudo black chaff. Pseudo black chaff can occur in varieties that carry the Sr2 stem rust resistance gene. The discoloration is expressed under warm and humid conditions.

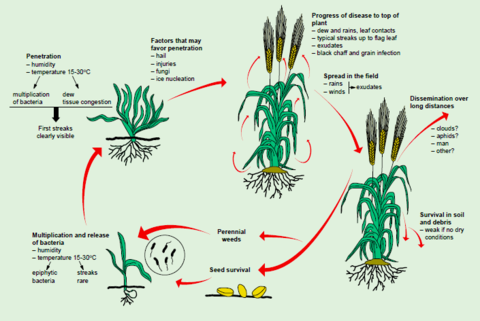

Xanthomonas translucens survives on and in seed, crop residue and perennial weeds (Figure 3). It has a limited ability to survive in soils without crop residue.

How it spreads

Infected seed is thought to be a primary method of distance dispersal. However, seed transmission studies haven’t been reproducible and there are no reliable seed detection assays.

BLS invades the plant either through leaf pores, known as stomata, or wounds caused by wind, hail, frost or farm machinery. The bacteria can spread by rain splash, irrigation, plant-to-plant contact and feeding insects, such as aphids.

Favorable conditions

Xanthomonas translucens has a relatively wide temperature range, but grows optimally at temperatures above 78 degrees Fahrenheit. It doesn’t appear to need free moisture for infection and disease development.

Although initial infection is probably favored by humidity, once the bacterium is inside the plant, humidity is no longer needed. Temperature becomes the important factor in the rate of bacterial growth.

BLS is more likely to occur in years when conditions are warm and humid, especially if the varieties planted are more susceptible and there are bacterial cells either in the environment or seed. Because of the incidental nature of BLS, it’s been hard to amass a consistent body of data regarding yield and quality losses.

Researchers found that, on average, yield losses were below 5 percent when the flag leaf’s infected area was less than 10 percent. When 50 percent of the flag leaf was infected, they observed losses of up to 20 percent. Preliminary research at the University of Minnesota indicates yield losses exceeding 30 percent are possible.

Management options

Fungicides and seed sanitation

Fungicides don’t control BLS. There are few bactericides labeled for use in wheat and barley (copper-containing compounds such as Kocide, Cuprofix Ultra and Champ). However, early trials show that while these can provide some control of BLS, results are often inconsistent.

Seed sanitation has also shown to be ineffective in Minnesota.

Genetic resistance

Consequently, as with many plant diseases, genetic resistance offers the most economic and effective control at this time. There are significant differences in how wheat cultivars react to BLS. Barley screening results are also available.

Variety trial results: Relative disease resistance of hard red spring wheat cultivars

Variety trial results: Relative disease resistance of barley varieties

Duveiller., E., Bragard, C., & Maraite, H. (1997). Bacterial leaf streak and black chaff caused by Xanthomonas translucens. In E. Duveiller, L. Fucikovsky & K. Rudolph (Eds.) The bacterial diseases of wheat: Concepts and methods of disease management (pp. 25-47). Mexico City, Mexico: CIMMYT.

Duveiller, E., & Maraite, H. (1993). Study on yield loss due to Xanthomonas campestris pv. undulosa in wheat under high rainfall temperate conditions. Zeitschrift für Pflanzenkrankheiten und Pflanzenschutz, 100, 453-459.

Reviewed in 2018