Submitting a soil test to a lab is the best way to determine the state of your soil. The soil test results will give you recommendations to improve plant performance, saving you time and money.

Why test your soil?

Soil tests provide a snapshot of your soil’s current nutrient levels, and can help you make smart decisions about how much to apply or whether to apply compost, manure or fertilizer.

A soil test can help you:

- Understand important physical characteristics of your soil including the texture, pH (acidity) and percent of organic matter in your soil.

- Determine if your soil needs nutrients and choose the right fertilizer.

- Test for contaminants.

- Add the right amount of compost or manure.

The three main nutrients that plants require for healthy growth are nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). Although they are already present in your soil to some degree, your N-P-K levels may not be optimal for plant growth. Your soil might lack potassium, for example, or you might have more than enough phosphorus. The goal is to make sure your plants are the most productive they can be without applying too many nutrients, which can lead to environmental issues.

When and what to test

Test your soil every three to five years and when you are making a change such as converting a lawn to a garden bed. It's good to test your soil in the spring before planting, or in the fall after you've harvested your garden.

The University of Minnesota Soil Testing Laboratory offers soil test services to the public. The test results will come with recommendations for fertilizing.

The regular soil test is sufficient for most lawns and gardens. The test results will give you the estimated soil texture, pH and percent of organic matter, and levels of phosphorus and potassium.

For an extra fee, you can also test for soluble salts, lead and trace elements such as calcium and magnesium; zinc, iron, copper and manganese; boron and nitrate (see the request sheet for more information).

High soluble salt levels can harm plants and reduce yield, while exposure to lead in soil is a health concern for humans, especially young children and pregnant adults. Trace elements are important for some crops.

Download the request sheet and find instructions from the soil testing lab site.

Collecting the soil sample is an important step in the process.

- Using a shovel or trowel, collect soil samples from various places in your garden, lawn or field.

- For raised beds or in a high tunnel, collect soil samples from the beds rather than the areas between them.

- In an orchard or vineyard, collect samples within rows between plants.

- Mix soil samples in a bucket. If your soil is wet, allow it to dry before putting about 1-2 cups of the mixed soil in a bag to submit for testing.

This step-by-step video (05:29) shows how to take a soil sample for testing.

Your local county Extension office can provide you with free soil sample bags and submission forms.

Find more information on managing soil and nutrients and your yard and garden.

Once you have submitted your sample to the lab, it takes about two weeks to receive your results.

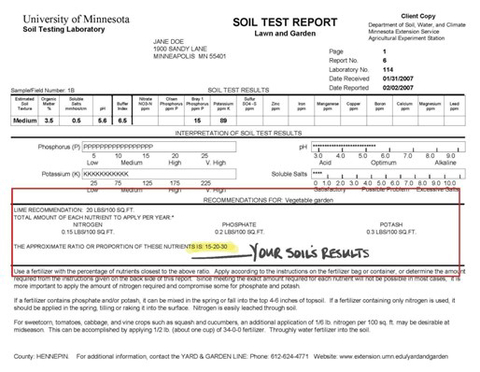

A regular soil test provides information on various aspects of your soil such as texture, organic matter and pH. Soil test results also include recommendations for fertilizer and additional soil amendments such as lime.

For more information on interpreting your soil test results, visit the Lawn, Garden and Landscape Plants page on the Soil Testing Lab’s website or read Soil Test Interpretations and Fertilizer Management (PDF).

Measuring the physical properties of soil

In addition to a soil test, you can take some simple measurements to better understand the physical properties of your soil. These measurements are informative, even if you only do them once. But if you do them each year, you can see how your soil is changing over time.

Over the years, hopefully, you will see that your soil structure is improving with the use of soil health practices like cover crops and reduced tillage. Take photos so you can document your results and refer to them in the future.

These methods have been popularized by the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

- Pick up a small handful of soil from your garden.

- Add water and knead it into the soil until it takes on a putty-like texture.

- Try to form a “ribbon” by pinching your soil.

The length of the ribbon can inform you about the texture of your soil.

The texture of your soil determines how it functions. Soil with more clay holds onto nutrients and water better than sandy soil. But it is also more prone to compaction and crusting, and it takes longer to warm up in the spring and to drain following heavy rainfall events.

Knowing your soil texture can inform your decisions about how much to fertilize, when you can plant and how often to water.

Your soil texture will not significantly change over time, so this is more of a baseline test than a test to do each year to measure progress.

A slake test can give you a sense of the stability of your soil during heavy rainfall events. It measures the stability of the aggregates in your soil.

An aggregate is essentially a “clump” of soil. These clumps include a mix of parent material (sand, silt, and clay), organic matter, pieces of plant roots, hyphae (long thread-like filaments) from fungi, and organic binding agents created by earthworms and microbes.

- Soil with stable aggregates is better able to withstand heavy rainfall events. Soil without stable aggregates tends to crumble in water and wash away.

- To do this test, take an aggregate, or clump of soil.

- Put a strainer or a piece of hardware cloth in a jar of water, almost like you are making tea.

- Set the clump of soil inside.

- If your soil has low stability, it will quickly dissolve.

- If your soil has excellent stability, the clump will remain mostly intact.

See the Sustainable Farming Association's video on how to do the slake test and the infiltration test.

An infiltration test measures how long it takes for your soil to absorb water. You can do this at home with a soup can.

- First, fill the can with one inch of water, then pour the water into a measuring cup to figure out how much water it takes to reach a 1-inch depth.

- Remove the bottom lid so it becomes a hollow cylinder.

- Then use a mallet to pound the can about 3 inches into the ground.

- Pour the volume of water you measured earlier into the can that’s been partially pounded into the soil, and see how long it takes for the soil to absorb the water.

Ideally, you would do this when the soil is fairly dry. If it absorbs very quickly, this is a good sign; your soil will be able to absorb water more quickly during heavy rainfall events. If it takes a long time, it’s a sign that you should work to reduce compaction in your garden, and potentially build organic matter.

Using cover crops is a great way to build your soil’s infiltration capacity over time.

See the Sustainable Farming Association's video on how to do the slake test and the infiltration test.

Simply looking at your soil can tell you a lot about your soil’s biological health. One method is to dig up a bucketful of soil (ideally, dig down 12 inches) and spread it across a tarp. Then dig through your soil looking for insects and earthworms.

In general, more earthworms indicate soil with improved drainage, porosity and organic matter. Try to identify the insects in your soil. Do this each year and compare how your soil’s earthworms and insects are changing over time.

Be aware that invasive jumping worms damage forest floors and should be reported to the DNR. Do not dump soil from your garden or field into natural wooded areas.

Listen to a podcast about tests for measuring soil biological health.

Applying fertilizer, manure or compost

If your soil test results indicate low organic matter (less than 3%) you may want to add compost or composted manure. It can be difficult to know how much nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium are in your compost and manure, and the amount of nutrients you are applying.

You should test your soil regularly to make sure you aren’t adding too much phosphorus, which can pollute water.

Because compost and manure often lack nitrogen, a soil test may recommend adding products that supply N without adding P and K that your soil doesn’t need.

Compost and manure add nutrients to your soil, but they often don't come with a labeled N-P-K ratio. While we recommend compost testing for farmers, it may not be practical for gardeners due to the cost. If you are using compost and manure, test your soil more often so that you can track how nutrients like phosphorus and potassium are building up in your soil.

Learn more about testing your compost.

Compost for building your soil

The following recommendations are for non-manure-based composts like composted food scraps or yard waste to use for soil-building. Treat composted manure as a source of fertilizer.

- Vegetable and flower gardens: enough to add about 1/2 inch of compost over the surface of your garden.

- Lawns: Sprinkle about 1/4 inch of compost on lawns (top-dressing).

You have choices when it comes to selecting a fertilizer. Fertilizers are available with different nutrient analyses (N-P-K). They may also be organic or synthetic, granular, water-soluble, slow-release or liquid. What kind of fertilizer you choose depends on the needs of your plants and your soil test results.

Fertilizers have N-P-K levels printed on the label. Choosing the right fertilizer product for your soil is also important for environmental reasons. If your soil test suggests a 15-20-30 ratio of N-P-K but you use a bag of 18-24-12 fertilizer, for example, it will result in too much phosphorus but not enough potassium. Repeated lawn and garden over-application of nitrogen and phosphorus can lead to environmental and water quality issues.

Soil can be over-fertilized and under-fertilized

Soil that requires nutrients applied at a 15-20-30 ratio of N-P-K, but is amended with a 10-10-10 fertilizer (a starter fertilizer), may result in your plants not having enough nutrients to reach their full potential. Long-term farming or gardening can deplete certain nutrients.

One issue you may run into when it comes time to apply fertilizer to your lawn or garden is deciding how much to apply. The instructions on the bag of fertilizer may not provide specific information for your garden size. Use the fertilizer calculator to convert pounds of fertilizer per acre to ounces of fertilizer per square foot.

N-P-K

Choose a fertilizer with the percentage of nutrients closest to your soil test recommendation. Since meeting the exact amount required for each nutrient will not be possible in most cases, it is more important to apply the amount of nitrogen required and compromise some for phosphate and potash.

Organic or inorganic

Choosing an organic or inorganic fertilizer depends on several factors.

- Organic fertilizers can improve soil drainage, aeration, and water and nutrient holding capacity. They are derived from animal or plant materials and contain less salt, so are less likely to burn plant roots. However, they require more time to be broken down so plants can use them, so they may not be immediately effective if a plant is showing signs of nutrient stress. Also, even organic fertilizers can be overused and negatively affect the environment.

- Inorganic fertilizers are made synthetically and contain salts that may burn plant roots if over-applied. Inorganic fertilizers are readily available for plants to use, so can help reduce plant nutrient stress fairly quickly.

Fertilizer form

Granular fertilizers and slow-release fertilizers are in pellet form and require watering (and time) to dissolve and release the nutrients into the soil. Water-soluble fertilizers are dissolved in water and applied immediately to plants. Liquid fertilizers are concentrated and added to water to create a solution.

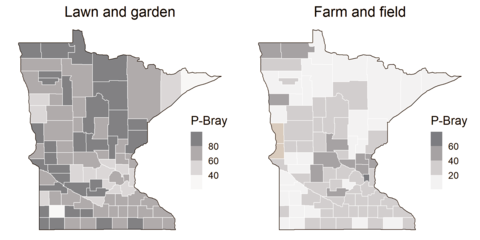

An analysis of soil tests completed at the University of Minnesota soil lab revealed that many Minnesota lawns and gardens have much more phosphorus than they need. Our research found that the median statewide soil phosphorus reading for results collected between 1988 and 2021 was 68 ppm (Bray) for lawns and gardens, compared to only 26 ppm (Bray) in farm fields. The Bray test is a method to extract phosphorus in soils with a pH of 7.4 or less. Some Minnesota soil tests may report phosphorus levels using the Olson extraction method if the soil pH is more than 7.4.

A reading of 20 ppm is considered sufficient for growing vegetables, and more than sufficient for lawns. In general, using too much phosphorus is a problem for water quality, and over-fertilizing is expensive. At high enough rates, it can also negatively impact plant growth.

Why it matters

Over-fertilizing lawns and gardens matters for a variety of reasons. When there is excess phosphorus in the environment, it can leach into lakes and rivers, causing toxic algal blooms.

Fertilizers, composts and other soil additives can also be expensive and they take time to apply, so cutting back can save time and money.

What you can do

- Take a soil test from your lawn or garden every few years. If your soil phosphorus levels are above 25 (Bray test) or 18 (Olsen test), do not use a phosphorus-containing fertilizer for a few years, until your levels drop to a point where your soil test recommends more phosphorus. Keep in mind that compost often contains phosphorus, especially if it contains manure.

- If you have enough phosphorus in your garden but still need nitrogen or potassium, consider options like feather meal or blood meal (nitrogen), and potassium sulfate or langbeinite (potassium). These products will not contribute excess phosphorus.

- If you add a thick layer of compost to your garden each year, consider your compost as a source of nutrients. Usually, compost has low nutrient concentrations, but when used in large volumes, or when using manure-based composts, the nutrient contributions can add up.

- Consider using cover crops in your garden. They can provide nitrogen and they build your soil health without adding extra phosphorus to your soil.

- Learn more about soil health for gardeners and visit UMN Extension Yard and Garden YouTube channel.

Small, G., Shrestha, P., Metson, G.S., Polsky, K., Jimenez, I., Kay, A. 2019. Excess phosphorus from compost applications in urban gardens creates potential pollution hotspots. Environmental Research Communications 1(2019)091007. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2515-7620/ab3b8c/meta

Reviewed in 2023