It is easy to see that this has been an unusually warm winter in Minnesota. Skis and sleds barely had a chance to get dusted off. People started tapping maple trees for syrup in February. Many people are worried about how this weather affects bees.

It is difficult to predict the effects of extremely different situations, but the few things we do know can help us guess what is happening.

Little snow but plenty of cold

We know that many bees hibernate a few inches underground. For these bees, temperatures are usually buffered by a layer of insulating snow. This year, we didn’t have much snow cover. However, our generally warmer weather didn’t stop a polar vortex.

A polar vortex occurs when ocean currents that have been warmed more than usual push north from the equator into the Arctic, bringing warm air with them. This warm air displaces arctic air at the north pole, which gets pushed southward into Minnesota. The polar vortex in mid-January brought air temperatures down to -8 F in the Twin Cities and it was -23 F in International Falls.

Without the insulating layer of snow, bees may have experienced cold beyond what they can tolerate.

Warmer weather stress

Aside from those few days of extreme cold, the warm weather could also cause stress to bees. Most bees survive the winter by using the fat they store in their bodies for fuel. When they are hibernating, their metabolism slows down and they don’t use much of their fat.

Some bees deplete their fat stores with warmer winter temperatures. This means that when they emerge in spring, they may be underweight and won’t have the nutrition they need to make babies.

They might be able to catch up if there are enough flowers around, but how will this warm weather affect flowers? Will bees be there at the right time to find the flowers they need?

Timing is everything

On aggregate, it seems that bees and flowers often match their timing. With flowers blooming earlier overall, many bees are also emerging earlier, at least generalist bees.

There are, unfortunately, many examples of specialist bees not matching with their hosts and suffering from poor nutrition, and also flowers that go unpollinated because they bloom before their pollinators have emerged.

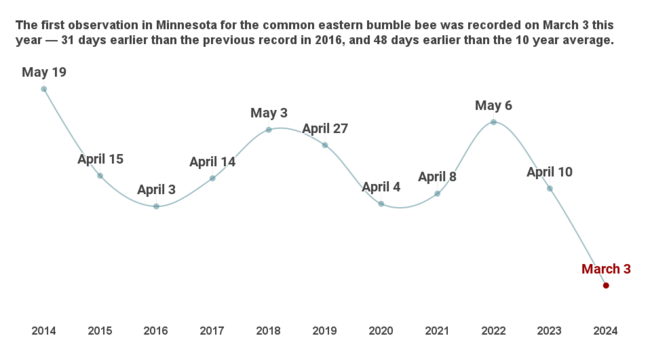

While there are many things we can only guess about, we have one clear piece of direct information we can share about the impact of the 2024 winter on Minnesota bees. On March 3, 2024, we saw the first record of emergence for the common eastern bumble bee, Bombus impatiens. Looking at records of common eastern bumble bees reported to iNaturalist and Bumble Bee Watch, the next earliest record is from April 3, 2014. All records from 2015 to 2023 fall between April 3 and May 7. This year is one for the record books for bumble bee queen emergence in Minnesota!

How will this early bee survive? A few things are blooming. She may find what she needs to start laying eggs and feeding babies, or she may not. We hope that she stays napping a bit longer.

In the grand scheme of things, it is important to have individuals pushing the boundaries. We need to have a mix of bees emerging earlier, later, and at just the right time so that whoever survives and is most successful can pass on their survival genes to the next generation. Let’s hope this weirdo living at the edge is one of the survivors.

Fliszkiewicz, M., Giejdasz, K., Wasielewski, O., & Krishnan, N. (2012). Influence of Winter Temperature and Simulated Climate Change on Body Mass and Fat Body Depletion during Diapause in Adults of the Solitary Bee, Osmia rufa (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). , 41, 1621 - 1630. https://doi.org/10.1603/EN12004.

Bartomeus I, Ascher JS, Wagner D, Danforth BN, Colla S, Kornbluth S, Winfree R. Climate-associated phenological advances in bee pollinators and bee-pollinated plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Dec 20;108(51):20645-9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115559108. Epub 2011 Dec 5. PMID: 22143794; PMCID: PMC3251156.