How will your family cope when faced with the dilemmas and decisions regarding the changing health and independence of aging parents? Long term care decisions regarding a range of issues — from how to pay the bills to caregiving roles — can challenge family relationships. Take time to understand potential sources of conflict in advance. Then learn strategies to avoid or reduce the impact of these common conflicts.

Sources of conflict

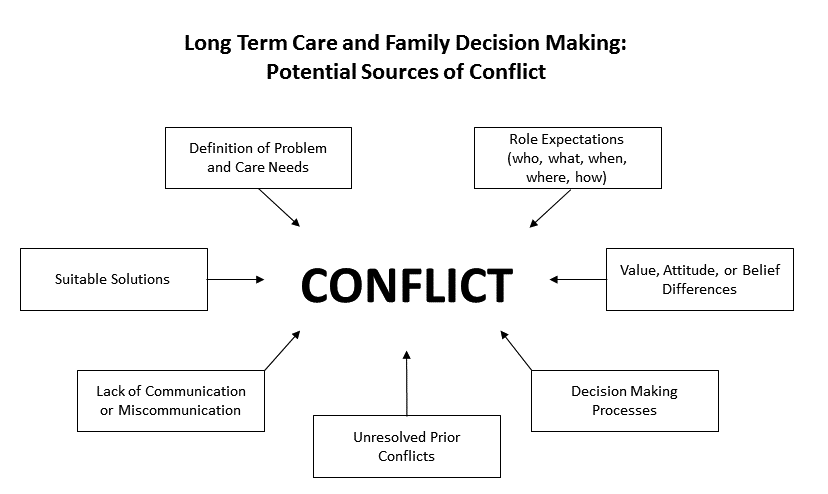

The experiences of families suggest that there are seven potential sources of conflict commonly experienced.

Definition of problem and care needs

Role expectations

Value, attitude, or belief differences

Decision making processes

Unresolved prior conflicts

Lack of communication or miscommunication

Suitable solutions

Families may disagree about one or many of these topics. A single conflict may have multiple sources. The diagram below identifies seven potential sources of conflict that can directly impact family decision making . In real life, multiple and interwoven sources of conflict are likely to be experienced by families adding complexity.

Strategies to avoid conflict

Here are seven strategies to avoid or reduce common family decision-making conflicts.

-

Take time to clarify the situation and the care needs with all involved family members.

-

Make sure that you inform all family members. Each should have the same explanations of disease, diagnosis, treatment options and potential consequences.

-

Develop a common understanding of the elder's condition and of care needs now and in the future.

-

Acknowledge that dementia and cognitive impairments may add ambiguity and uncertainty.

-

Identify reasonable and appropriate goals. Accept the limits of recovery and avoid exaggerating the extent of the crises.

Clarifying different perceptions about suitable solutions — that is, quality and quantity of care — includes making clear the role of informal and formal support systems.

-

Recognize that there are no "right" ways or absolute answers for most care needs. Also recognize that there can be very simple answers and wrong answers.

-

Take time to learn about the elder's disease, options for care and potential consequences for those involved.

-

Understand that family members providing care can contribute to "learned helplessness." This may happen when they don't set limits on when and how much help they provide. Instead of maintaining the elder's independence, the family members may contribute to the elder's dependency.

-

Negotiate the provision of help with elderly parents. Parents may not like to ask for help or accept it because of feelings of loss of pride or loss of power. They may take it as an insult. Help elderly parents know how to ask for and accept help.

-

Discuss values and make them explicit as decisions are made. It's often easier for a third party (professionals, in-laws, mediators) outsider to point out values heard through actions or words.

-

Identify where agreement can be reached. What values or beliefs do family members agree on? Identify and build on strengths within the family.

-

Identify personal limits of family members. This will help avoid negative consequences on both their mental and physical health. It will also help identify opportunity costs or what they personally will need to give up to help meet the needs of the older person.

-

If some areas continue to have conflict, work out how to "agree to disagree.”

Clarify and renegotiate roles figuring out fit

-

Discuss the various roles needed. What has to get done? What skills are needed?

-

Try to find a "best fit" between roles needed and abilities and interests of family members. Develop a common understanding. Ask about each family member's expectations, availability and willingness to provide care.

-

Discuss what "fair" means for each family member. Get unwritten rules and assumptions out on the table. Acknowledge that different perceptions are normal and should be expected.

-

Discuss the difference between “equal” (everyone helping the same amount) and “equitable” (what is fair given each individual situation). Talk about the difficulties in measuring and comparing different types of contributions. Help family members recognize that equal or fair distribution of responsibility may not always be in the best interest of the care recipient or available caregivers. Identify resources and competing demands among family members.

-

Find out what else is going on in people's lives beyond the disease/illness. What events and activities are placing demands on their time and other resources?

-

Identify competing intergenerational demands. What needs do the grandchildren or children have that need to be met?

-

Clarify expectations and identify potential conflicts among all family members and generations who may be affected by caregiving. Discuss any fears individuals may have.

-

Revisit the fit with caregiving roles, "who is doing what." Caregiving may differ from one's expectations of what it will be like.

Impact of caregiving

-

Provide realistic projections of the impact of the care plan on family members.

-

Learn how to apply procedures, treatments, give medication, or help with personal care routines. Don't assume family members automatically know how to care for their relative. Caregivers typically mention needing help to address emotional and behavioral, physical and safety, legal, and financial needs of an older person's care.

-

Gather tools and resources to help family members with their own physical and mental health needs.

-

Create a balance in informal and formal support systems. Protect the family from trying to do too much, as well as from “denying and dumping.”

-

Recognize that grieving may occur and need to be acknowledged as losses related to a chronic illness unfold.

-

Keep all family members informed.

-

Get unwritten and unspoken feelings out in the open to talk about.

-

Provide opportunities for each family member to have time to express his/her point of view with respect and without interruption.

-

Focus on the issue, not on personalities.

-

Listen with empathy and without interruption.

-

Have family meetings or conferences to share feelings, provide updates on the care plan and to reach agreements on responsibilities.

-

Use written or text options if verbal communication is difficult or uncomfortable.

-

Listen to and believe the perceptions of hands-on local caregivers.

-

Acknowledge the inability to "control" the situation and the frustration this may cause.

-

Share information in different ways (e.g. virtual or in person family meetings, utilize technology and phone calls).

-

Adjust timelines and decision making processes to accommodate different styles.

-

Know that if someone is in denial about the situation, the denial may get in the way of making decisions.

-

Recognize some involved may want to gather and use a variety of information and community resources; others may not.

The following intentional and transparent steps can help to improve decision processes and outcomes for all involved:

Step 1: Clarify how each person views the problem.

If you are the one who first becomes aware of a problem, seek clarification of the problem from those involved in the outcome. First find out if they too are concerned. Try to identify whether what is actually happening differs from what they would like to have happen.

Step 2: Make a commitment to work on the problem.

If others agree that change is desirable, then get a definite commitment from them to think about possible solutions.

Step 3: State personal needs.

The goal is to define the problem before generating alternative solutions. Give each person a chance to state his or her priority values and particular needs. Each person needs to explain how what is happening is different from what needs to happen.

Allow a time delay between stating personal needs and considering alternatives. The delay allows time for tensions to decrease. It could be anywhere from an hour or two to one or two days, depending on tension levels. Assign each person the homework of creatively thinking about alternatives.

Step 4: Consider the alternatives.

Find creative alternatives by brainstorming without analyzing possible negative or positive effects. The more ideas created, the better. Ideas are generated first by the individuals and are then combined to simultaneously meet the needs of several people. Again, plan a time delay, but make it longer than the previous delay to give private time for thinking as well as tension release.

Step 5: Select a solution.

There are two objectives:

-

Analyze the goal and value issues of the family members.

-

Study how the preferred solutions protect these values and allow for individual needs.

Discuss the pros and cons of each alternative. Examine the situations to discover if you are willing to accept the results of one or another of the alternatives.

You may or may not need more time before deciding which alternative best meets the conflicting values and needs of the older person and other family members. This will depend upon tension levels that surfaced during your negotiations. When there is an agreed upon goal and a willingness to commit time, money, and human energy to the action plan, then everyone has clearly accepted the solution. If this does not happen, you may need to go back to step one and re-clarify the problem.

Step 6: Evaluate the choice.

Set a trial period for the accepted solution. Having a trial period may be less threatening than a hard and fast decision. It may allow everyone to cooperate because they know that it is not a "forever" commitment. Plan to review the new strategy soon after it has started and to discuss how it is working. Then make any necessary adjustments. The people involved need to discuss whether their most important values are being preserved. Successful decisions may bring people closer together and improve future communication.

Barnett, A. & M.S. Stum. (2012). Couples managing the risk of financing long term care. Journal of Family & Economic Issues. 33, 363-375.

Cicirelli, V. (1992). Family caregiving: Autonomous and paternalistic decision making. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Danes, S., & Rettig, K. D. (1986). Solving family problems involves social decision making. St. Paul, MN: University of Minnesota Extension.

Gwyther, L. (1995). When "the family" is not one voice: Conflict in caregiving families. Journal of Case Management, 4(4), 150-155.

Stum, M. (2007). Financing long term care: Risk management intentions and behaviors of couples. Financial Counseling and Planning. 17(2), 79-89.

Stum, M. (2001). Financing long term care: Examining decision outcomes and systemic influences from the perspective of family members. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 22(1), 25-53.

Stum, M. (2000). Later life financial security: Examining the meaning attributed to goals when coping with long term care. Financial Counseling and Planning, 11(1), 25-37.

Reviewed in 2022