This information is specifically for those managing black cutworm on crops.

Find information about black cutworm in Minnesota corn, including their characteristics, habitat, at-risk fields, signs of damage and strategies for managing infestations.

Distribution

The black cutworm – Agrostis ipsilon Hüfnagel (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) – is widely distributed in the temperate regions of the world. Although a native of North America, it can’t survive winters in Minnesota or other latitudes with freezing winter temperatures. In these areas, annual infestations are produced by moths migrating from southern overwintering areas each spring.

Host range

The larva -caterpillar - is the life stage that damages crops. In addition to corn, the larvae feed on a wide range of broadleaf and grass crops, weeds and other plants. Black cutworm adults feed on plant nectar.

Description and life cycle

The black cutworm goes through a complete metamorphosis with egg, larval, pupal and adult stages. Depending on when the moths arrive in Minnesota and temperatures, black cutworms will go through one or more generations until late-summer conditions trigger a southward migration.

Adult

The adult black cutworm is a moderate-sized moth with a wingspan of about 1.5 inches (Figure 1). The forewing is dark brown to black with a lighter distal - away from the body when spread for flight - edge.

Identifying features include a small black dagger or dart-shaped mark that extends outward from a faint kidney-reniform spot near the light-to-dark boundary of the forewing.

The hindwings do not have obvious markings and are pale gray with darker gray near the veins and edges.

These markings on the wings are most visible on newly emerged or recently arrived specimens with intact wing scales. Moths become difficult to identify when they lose their wing scales and markings with age or when otherwise damaged.

Egg

Eggs produced by spring migrant moths are often laid before crops are planted.

The female moth can lay 1,000 eggs or more, singly or in small groups of up to 30 on grasses, weeds and crop debris. Females seek low-lying and weedy areas to lay eggs.

While not winter-hardy, the black cutworm eggs can tolerate colder temperatures more than other life stages. Eggs hatch in five to 10 days depending on temperature.

Larva

Black cutworm larvae are gray to nearly black, with a light dorsal band and a ventral surface that is lighter in color (Figure 2). The distinct head is dark brown. The larvae have three pairs of true legs and five sets of fleshy prolegs (4 abdominal and one anal).

Overall, the larva has a greasy appearance; earning the common name “greasy cutworm” in some parts of the world.

Under magnification, the skin of larger larvae has a granular appearance. Black cutworm larvae can be distinguished from the more common dingy cutworm and several other corn-attacking species by the unequally sized small, dark, wart-like bumps - called tubercles- on the upper edges of each body segment.

On the black cutworm, the front tubercle is smaller than the rear. On most other cutworm species, these tubercles are nearly equal in size (Figure 3).

As they grow, cutworm larvae molt and pass through several larval stages or instars. There can be from six to nine larval instars, but seven instars are most common. Diet influences the number of larval instars, with a less suitable diet leading to prolonged development and more instars. A full-grown larva is about 2 inches long.

Larval development from egg hatch to pupa takes approximately 28 to 35 days, depending on temperature.

Pupa

The mature larva burrows into the soil and forms an earthen cell where it pupates. The naked pupa is approximately 3/4 inches in length. It is initially orange-brown, becoming dark brown as it develops (Figure 4). The pupal stage lasts 12-15 days.

The temperatures encountered by the pupae are suspected to determine whether the resulting moths remain in the area, and migrate north in the spring or south in the fall.

The entire life cycle from egg to adult takes 35 to 60 days, depending on temperature and food quality. Multiple generations are produced until weather conditions trigger southward migration.

Crop damage

Plant tissues are damaged by the chewing mouthparts of the feeding larva. Larvae are active, moving and feeding mainly at night.

Small larvae feed on leaves, creating irregular holes and can cut small weed seedlings.

While feeding near or below the soil surface, 4th instar and larger larvae can cut off corn plants (Figure 5), sometimes dragging the cut plants below ground. Plants cut above the shoot apical meristem (growing point) usually recover. This meristem remains below the soil surface until the 5th leaf and later corn stages. In contrast, the dingy cutworm, a species commonly confused with black cutworm, cuts plants at or above the soil line.

Dry soil conditions can encourage cutting below ground, at or below the growing point. When corn emergence is delayed by late planting or cold soils, it's vulnerable to waiting cutworms that can cut it off before it emerges.

When corn plants are too large to cut (after 5th leaf stage), late instar larvae tunnel into the stem. This may kill the plant by cutting water and nutrient flow or by damaging the growing point.

Most biomass is consumed during feeding of the last two larval instars.

Natural enemies

A range of fly, wasp and nematode parasites have been isolated from black cutworm larvae. Cutworms can also be infected by viral and bacterial pathogens. Bird, mammal and insect predators (notably ground beetles) also impact cutworm larval populations. Birds, bats and motor vehicles prey on adults.

Long-range migration and field risk

Two or more generations of the black cutworm occur in Minnesota. Typically, only the first generation larvae, produced by migrant moths, are damaging to corn.

The migration habits of the black cutworm have been documented on several continents. North American black cutworm moths use prevailing winds help them move north in the spring and south in the fall.

In central United States, black cutworm moths migrate northward from over-wintering areas near the Gulf of Mexico, Texas and northern Mexico when appropriate weather systems occur.

Long distance migration

Black cutworm moths can move short distances north on their own, but they take advantage of a much more efficient transport method to move long distances quickly. In the spring, moths can make it from southern Texas to Minnesota within two days.

How do they do it? The moths hitch a ride on nocturnal low-level jet streams. These efficient transport systems are a common feature of the Great Plains in spring and summer. They’re used not only by black cutworm moths; other migrant lepidopterans, aphids, leafhoppers and even rust spores take advantage of this rapid transport system.

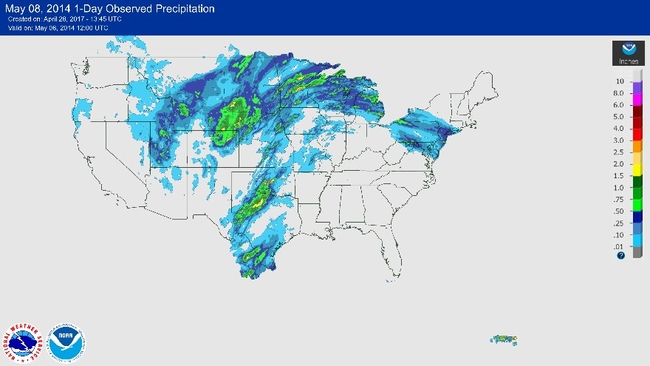

In North America, an approaching cool, dry, low pressure center in the western plains interacts with moist, high pressure systems in the eastern plains to create strong southerly flows. They are particularly strong at night (Figure 6).

Each winter, black cutworms are presumed to overwinter only as far north as topsoil remains unfrozen. Emigrating moths fly upward from the overwintering areas at dusk. If weather systems cooperate, they’re whisked off by surface winds and rising air in advance of thunderstorms into the lower-level jet stream.

These winds are strongest at night, moving at 30 to 80 miles per hour, and can occur from about 330 to 3,000 feet in altitude. The flight is mostly passive with moths carried along until they decide to “drop out,” encounter air too cold for flight or rain out in thunderstorms. These migrating moths arrive in the north in excellent shape.

The ideal weather pattern for spring migration into Minnesota involves a high pressure center to our east with a strong low pressure center approaching from the west. This pattern produces strong, persistent southerly winds that can bring black cutworm moths northward.

Conditions that support long distance migration to Minnesota

Two ingredients are necessary for black cutworm moths to arrive in Minnesota.

First, the air parcels reaching Minnesota must have passed through the overwintering areas when migrating adults are present. Second, the track of the low pressure center is critical. If the low tracks too far south, migration is cut off south of Minnesota. If the low tracks through Minnesota or northern Iowa we have the potential for moths to drop out into Minnesota.

These weather systems may stall with the frontal boundary cutting across Minnesota. In that case, if you’re south and east of the front, watch out! Moths often drop out of the edges of heavy rainfall. Several lows may ripple across the stationary front, pumping moist air northward and compounding moth deposition in Minnesota.

Radar studies in the 1980s found most evening migrating insects move at an altitude of 1700 feet or so. Wind trajectories can be used to estimate where an immigration event might have originated.

Although they are not cold hardy, black cutworms are not predestined to die from exposure to frigid Minnesota winters. In the late summer and fall, southerly flows on the back side of cold fronts aid the migration of a generation of moths to the south.

Field topography, tillage and crop rotation

Black cutworm moths arriving in Minnesota seek out areas with crop debris, sheltered areas and low spots in the field to lay eggs. Early-season weed growth is very attractive to the moths. Areas with dense populations of winter annual (e.g. shepherdspurse, Capsella bursa-pastoris L.) and early-spring emerging (e.g., lambsquarters, Chenopodium album L.) broadleaf weeds are often infested (Figure 7).

Similarly, the early season growth of overwintering cover crops and associated broadleaf weed growth might attract egg-laying moths. For example, black cutworm damage has been observed in corn planted into a winter rye cover crop.

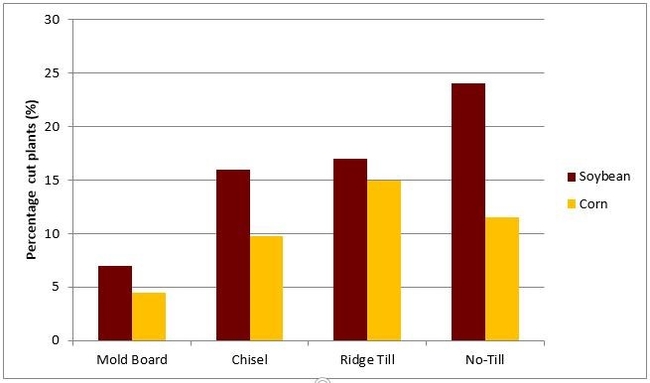

Egg-laying black cutworm moths are less attracted to fields already tilled in the spring. Unworked fields or fields with reduced tillage where more crop debris is on the surface attract more egg-laying moths.

The higher risk of black cutworm attack associated with crop residues and tillage can be seen in tillage plots at the Southern Research and Outreach Center in Waseca during 1985 (Figure 8) and 1986 and the Southwest Research and Outreach Center near Lamberton during 2001 (Table 1).

Table 1: Black cutworm damage to corn as affected by soybean tillage (crop residue and weed growth).

| Tillage system | Corn plants cut: Waseca1 | Corn plants cut: Lamberton2 |

|---|---|---|

| Fall moldboard plow | 5.0% | -- |

| Fall chisel plow | 10.1% | 1.4% |

| Spring field cultivation | -- | 3.0% |

| Ridge till | 14.7% | 7.9% |

| No-till | 10.2% | 1.0% |

| Fall strip-till | -- | 4.0% |

| Spring strip-till | -- | 9.2% |

1Waseca, MN, 1986.

2Lamberton, MN,2001.

Source: K. Ostlie and B. Potter.

Fall tillage that buries crop residue and spring tillage that eliminates early spring weed growth before the flight arrives reduces the risk and severity of black cutworm attack in a field.

Historically, soybean residue is more attractive than corn, but this may be parially due to the amount of fall tillage or to species and numbers of broadleaf weeds in the seedbank between the two crops.

In 2019, economic damage was observed in areas of corn and soybean fields that had been drowned out and weedy the previous summer.

Management

Yield-limiting black cutworm infestations are relatively rare in Minnesota and when they do occur, require several factors to coincide:

A large number of moths produced in the overwintering areas.

The proper weather systems, at the right time, to aid moth migration into the state.

Attractive and suitable sites for egg laying that will be planted are planted to susceptible crops (e.g., late emerging corn).

Conditions favorable for black cutworm egg and larva survival.

Although infestations can be devastating, the rarity of black cutworm problems indicates that insurance management tactics for black cutworm seldom pay. Scouting and rescue insecticide applications are the best defense against yield loss from black cutworm.

Predicting black cutworm development and damage

You can predict black cutworm development and damage using pheromone traps and degree-days.

Like most other moths, black cutworms are attracted to light. Black light traps capture both male and female moths throughout the flight but captures aren’t predictive of moth density.

In addition to lights, male moths are attracted to a chemical sex lure (sex pheromone) released by females. Pheromone traps use a synthetic version of this sex pheromone and for a short period after they arrive, unmated migrant males are attracted to the traps (Figures 9 and 10). These captures can be used to estimate moth population density and predict the potential for crop damage.

Since insects are cold blooded, their activities, including how quickly they grow, depends on the temperature of their environment. The effect of temperature on growth is known as temperature-dependent development.

Black cutworm larvae grow and develop faster when exposed to more cumulative heat. Similar to predicting corn growth with degree day accumulations (a.k.a. growing degree, heat units, growing degree days), degree-days can be used to predict what development stage the cutworm eggs, larvae or pupae would be.

How to calculate degree-days

There are several ways to calculate degree-days for insect development, but the simple model works fine for crops and black cutworm.

First, you need to know the maximum and minimum daily temperatures. Secondly, you also need to know the minimum temperature (lower development threshold or base temperature) at which cutworm growth occurs. Conveniently, we can use a 50 degree Fahrenheit lower developmental threshold for both corn and black cutworms.

The degree-day concept is not exact under field conditions. Temperatures where the eggs and larvae are located will be slightly different than air temperatures. Development ceases at an upper temperature threshold (e.g. 86 degrees F. for corn plants). Individual life stages can have different threshold temperatures and temperature-dependent development rates. Some black cutworms go through fewer or extra larval stages - or instars.

Fortunately, for our purposes, these subtleties can be ignored and we can use the following equation:

A daily degree day accumulation = ((Maximum temperature + minimum temperature) / 2) - developmental threshold temperature

For an example of calculating degree-day accumulations: The daily high was 70 and the daily low was 48. The degree-day accumulation would be:

((70+48) / 2) – 50 = 9

Daily degree-day accumulations are summed over the time period of interest.

When to start degree-day accumulations

To know when to start the degree-day accumulations we need a “biofix.” That biofix is a significant moth capture (Eight or more moths over a consecutive two-night period) and is where the black cutworm pheromone trapping network comes in.

The black cutworm life cycle, from egg to moth, takes 1.5 months or more. Only cutworm larvae 4th instar or larger can cut corn plants. Degree-days can be used to predict when larvae will be large enough to cause visible damage, begin to cut corn and when they cease feeding (Table 2). The simple degree-day model for development predicts that larvae are large enough to cut plants when more than 300 degree-days have accumulated after a significant moth flight.

Scouting corn for black cutworms should start before 300 degree-days accumulate after a significant catch. This is about three weeks in a typical Minnesota spring, but will happen sooner if warm and later if cool.

Note: Comparing recent Minnesota black cutworm pheromone trap captures to reports of crop damage caused by larvae indicates the 8 moths / 2-night biofix predicts timing of larval development well, but tends to overpredict risk for area fields.

Table 2: Temperature dependent development and feeding damage of the black cutworm

| Cumulative degree-days (base 50 degrees Fahrenheit) | Stage | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (biofix) | Significant moth capture | Egg-laying |

| 90 | Egg hatch | -- |

| 91-311 | 1st to 3rd instar | Leaf feeding |

| 312-364 | 4th instar | Cutting begins |

| 365-430 | 5th instar | Cutting |

| 431-640 | 6th to 7th instar | Cutting slows |

| 641-989 | Pupa | No feeding |

Scouting for black cutworm

Scouting for cutworms is easily combined with stand evaluations and scouting weeds for herbicide selection and application timing.

The first sign of black cutworm damage is leaf feeding on emerged corn or weeds. Sometimes, larvae will cut weeds before they move to corn. Any partially cut plants will wilt. In dry, windy weather, cut leaves or plants rapidly wilt, dry and may blow away to leave no sign except missing stand (Figures 11 and 12).

Be wary when lambsquarters and ragweed patches begin to disappear without the aid of an herbicide. Herbicide applications may cause cutworms to switch from feeding on weeds to corn.

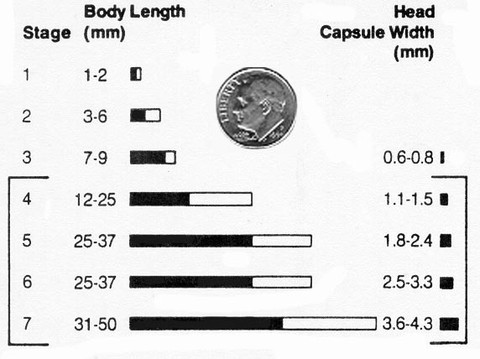

The leaf feeding and missing or cut plants caused by cutworms are not hard to see, but it is useful to find a few of the larvae that caused the damage to determine size and species. This can be frustrating, so why bother? Knowing the size of the cutworm larvae will help determine the potential for future damage (Figure 23).

Cutworms reduce yield by decreasing final stand or plant population. The generic economic threshold for black cutworm in corn is 2 to 3 percent of the plants cut or wilted when the larvae are less than 3/4 inch long.

The threshold increases to 5 percent cut plants when larvae are larger. However, with high corn prices, these thresholds could be lowered to 1 percent wilted or cut and small larvae and 2 to 3 percent wilted or cut for large larvae.

Remember to take into consideration corn populations in individual fields and adjust threshold numbers accordingly. For example, if the current plant population is at or near yield-limiting levels, you can afford to lose fewer plants than in a field with a higher emerged population. Table 3 shows the role of corn plant stands in determining yields.

Table 3. Corn yield response to plant population (Morris, Lamberton and Waseca, 2009-2011).

| Final corn stand | Expected yield |

|---|---|

| 44,000 plants per acre | 100% |

| 41,000 plants per acre | 100% |

| 38,000 plants per acre | 100% |

| 35,000 plants per acre | 100% |

| 32,000 plants per acre | 100% |

| 29,000 plants per acre | 99% |

| 26,000 plants per acre | 98% |

| 23,000 plants per acre | 92% |

| 20,000 plants per acre | 87% |

| 17,000 plants per acre | 81% |

Planting date factors into replant decisions as the season progresses. Finding a stand loss late compounds the replant decision. The UMN Extension publication Corn grower's guide for evaluating crop damage and replant options includes information on the effect of corn stand, planting date, and hybrid relative maturity on yield.

The reason the black cutworm economic threshold varies by larval size is based in remaining larval feeding. Cutworms must shed their skins (molt) to grow. The stage between molts is called a larval instar.

Cutworms will begin to cut corn at the 4th instar (~½ inch long). The smaller larvae tend to cut corn at or near the soil surface while larger larvae tend to feed below ground. The larvae are full grown and cease feeding between 1½ and 2 inches long.

While larger larvae will cut or tunnel into larger plants, they have less time left to feed and as a result, cut fewer plants. Table 4 and Figure 23 give approximate sizes in body length and head width for black cutworm larval stages.

Table 4. Black cutworm body and head capsule sizes by instar stage.

| Instar | Body length (mm) | Head capsule width (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 - 2 | 0.3 |

| 2 | 3 - 6 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 7 - 9 | 0.6 - 0.8 |

| 4 | 12 - 25 | 1.1 - 1.5 |

| 5 | 25 - 37 | 1.8 - 2.4 |

| 6 | 30 - 35 | 2.5 - 3.3 |

| 7 | 31 - 50 | 3.6 - 4.3 |

There are more detailed dynamic black cutworm thresholds available that use stand, crop stage, projected damage and crop price. However, caution is advised when dynamic thresholds generate lower thresholds below those described above.

Yield loss, actual or measurable, doesn’t begin with the first missing corn plant. High grain prices and a good planted and emerged stand means you could easily be treating cutworm populations that wouldn’t reduce stand enough to hurt yields.

The rescue insecticide calculator (Tables 5 and 6) is adapted from a University of Illinois publication and is an example of a dynamic threshold that’s used in several management guides.

Modern corn yields and prices could indicate treatment at a very low percentage cut plants using this worksheet, perhaps leading to over-reactive treatment decisions. However, the yield loss factors are still useful when combined with yield loss by stand reduction charts.

Table 5. Yield loss factors and equations to calculate the profitability of a rescue insecticide treatment for black cutworm when moisture is not limiting. Source: University of Illinois

| Average cutworm instar | 1 corn leaf | 2 corn leaves | 3 corn leaves | 4 corn leaves | 5 corn leaves |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| 5 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| 6 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

Table 6. Yield loss factors and equations to calculate the profitability of a rescue insecticide treatment for black cutworm when moisture is limiting. Source: University of Illinois

| Average cutworm instar | 1 corn leaf | 2 corn leaves | 3 corn leaves | 4 corn leaves | 5 corn leaves |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| 5 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 6 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 |

Equations

Projected bushels per acre yield loss = _______ yield loss factor x _______% plants cut (decimal) x _______expected yield (bushels per acre)

Projected money loss per acre = _______bushels per acre loss x $_______(price per bushel)

Preventable loss per acre = $_______projected loss per acre a x _______% control*

*95 percent control with adequate moisture, 80 percent control with limited moisture

$ return (+/-) for insecticide treatment = $_______ preventable loss/a - $_______ control cost per acre

1. Determine average instar of the black cutworm larvae and corn leaves (collars).

2. Consider soil moisture inadequate if the top 3-4 inches are dry and rain is not forecast.

Controlling black cutworm

Bt hybrids

Bt hybrids containing the Cry1F protein (Herculex /HX1) or Vip3a protein (Viptera), alone or in stacks, are labeled as controlling black cutworm. While they reduce risk, corn might still be damaged under heavy cutworm pressure.

An at-plant insecticide is probably not that helpful in preventing additional cutworm stand loss when added on these hybrids. Remember, the Cry34/35 Ab1 (Herculex RW protein) is not the same as the Cry1F above-ground protein.

In addition to timing of tillage, spring weed and cover crop growth, the Bt protein in the planted hybrid can help prioritize fields for scouting. The Handy B corn trait table shows which Bt proteins control black cutworm and several other insect species.

Seed treatments

High rates of neonicotinoid seed treatments (e.g., Poncho, Cruiser, Gaucho) are very effective on many seed and seedling insects and they can provide some protection against black cutworm. They may not always provide satisfactory cutworm control, however. Seed-applied diamide insecticides (e. g. chlorantaniliprole) can also affect black cutworm larvae.

Large numbers of late-instar cutworms moving from weeds to take a bite of corn can overwhelm seed-applied insecticides and Bt in corn tissues.

Concerns about Bt-resistant corn rootworm populations have led some farmers and ag advisors to add a soil insecticide to Bt-RW corn for added root protection. That decision, however, should be considered an entirely separate issue than cutworm management.

Soil-applied insecticides

Soil-applied insecticides at planting can provide control of cutworm larvae. However, they are not recommended as insurance applications for two reasons. At planting, it is difficult to predict which individual fields will have economically damaging cutworm infestations. Secondly, post-emerge insecticide rescue treatments work very well and can be targeted to fields with actual infestations.

T-band applications for granular insecticides, if so labeled, are sometimes more effective on cutworm than in-furrow applications. However, a t-banded insecticide has its own performance risks and the placement is not necessarily more effective on corn rootworm. Incorporate the insecticide bands as indicated on the label. Windy planting conditions reduce the accuracy of band placement and later blowing of loose, dry soils can also reduce efficacy of non-incorporated bands. Always read the pesticide labels and use the appropriate rates.

Foliar insecticide applications

Fortunately, cutworms are controlled well with rescue insecticide applications and many post-plant insecticide products provide effective control of black cutworms. Several compounds within the pyrethroid, organophosphate, carbamate, and diamide groups are labeled for post plant/post-emerge cutworm control. Spot treatments can be effective when combined with careful scouting.

Black cutworms tend to remain lower in the soil when the top few inches of the soil profile are dry, meaning that insecticide applications can be less effective. A rotary hoe or row cultivation before application (or after application if below-ground feeding continues) can help improve the efficacy of some insecticides by incorporating insecticides and encouraging cutworm movement.

Good coverage of row area and plants is important. Do not skimp on water and match spray volume and pressure to nozzles designed for insecticide application. Although spraying in the late afternoon or evening will place the insecticides in the field closer to larval activity, it can also reduce control if a temperature inversion prevents the spray from settling on the field.

Make sure cutworms are still present and actively feeding if you decide to treat. Check just before spraying to ensure stand loss is still progressing.

CAUTIONS

It is important to read pesticide labels. Be cautious of potential interactions between some organophosphate insecticides (e.g., Thimet, Counter, Lorsban) and some ALS herbicides. These interactions can cause severe or temporary crop injury. Some PPO and HPPD herbicides may also interact with insecticides.

Cultural control

Maintain good early-season weed control, including the timely termination of cover crops, can reduce the attractiveness of fields to egg-laying females.

Some above-ground Bt traits effective on European corn borer also have some effect on black cutworms and can be considered in high-risk situations.

Tillage after egg laying has little impact on either egg or larval survival, unless the field is kept black for a couple weeks after egg hatch. This is long enough to starve the larvae but unfortunately, is a yield-adverse planting strategy.

Comparisons and photos of other cutworms

Black cutworms are not the only cutworm species than can injure crops in Minnesota. As corn (and other row crops) germinate and begin to emerge they can be attacked by several species of cutworms.

Table 6 lists some of the species that might be found in Minnesota corn fields. Most species can overwinter in Minnesota as eggs or larvae. Black and variegated cutworms cannot winter here and migrate into the state each spring.

While we can project cutting dates for the black cutworm, corn should be scouted for other cutworm species as soon as it emerges.

Because cutworms that overwinter, particularly those that winter as larvae, begin development before migrant black cutworms arrive, they’re ready to feed on corn early. Often, the first corn leaf feeding observed in the spring is from overwintered dingy cutworm larvae.

Dingy cutworms are commonly found in corn, but unlike black cutworms are seldom a threat. With a bit of practice, the two species are easily distinguished by the size of paired black bumps (tubercles) on the upper edges of each segment. These tubercles are unequal in size on the black cutworm.

Other Minnesota insects that cause damage to larger corn and might be confused with cutworm include the hop vine borer and common stalk borer. Some of the insect larvae commonly observed in corn are shown in Figures 13-22.

Particular habitats are preferred by most cutworm species (Table 6). For example, sandhill cutworms are found in sandy soils and several species tend to be problems in crops planted into sod. Dingy cutworms are often abundant when corn is planted after alfalfa or fields that were weedy the previous year.

Table 6: Some cutworm species found in Minnesota corn

| Species | Eggs laid in | Number of generations | Overwinters as | Likely habitat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | Spring-summer | 3 | Adults migrate | Late-tilled fields |

| Bronzed | Fall | 1 | Eggs/larvae | After sod |

| Claybacked | Fall | 1 | Larvae | After sod |

| Darksided | Summer | 1 | Eggs | After weedy crop |

| Dingy | Summer-fall | 1 | Larvae | After sod, alfalfa |

| Glassy | Summer-fall | 1 | Larvae | After sod |

| Redbacked | Fall | 1 | Eggs | After weedy crop |

| Sandhill | Summer-fall | 1 | Larvae | Sandy soils |

| Variegated | Spring-summer | 2 | Adults migrate | In and after alfalfa |

Why it’s important to identify the species

Species identification is important to determine damage potential. Small larvae of all species feed on weeds and leaves and cannot cut corn. In addition to dingy cutworms, redbacked, spotted, and variegated cutworms are primarily leaf feeders feeding at or above the soil surface. Consequently, these climbing cutworms don’t usually cut corn below the soil line and growing point and the plant recovers.

However, unlike the climbing cutworms, the larvae of some cutworm species (e.g., glassy, sandhill, darksided, claybacked and black) tend to feed below ground at or below the growing point. This potential for feeding to kill corn plants makes black cutworm a threat.

When larger larvae tunnel into the growing point, corn as large as 5 or 6 leaves can be killed. Fortunately, damaging black cutworm populations are infrequently encountered.

What about other crops?

The growing points of broadleaf crops are above ground. Plants will be killed if cut below the cotyledons; even climbing cutworm species can be a threat. Since yield loss from cutworms is related to stand loss, crops that are less able to compensate for stand loss are at greater risk.

While black cutworm larvae will cut soybeans, they are less likely to create a yield limiting problem in this crop. Soybeans are seeded at a much higher plant density and can compensate (up to a point) for reduced stand much better than corn.

Sugarbeets are at risk because of yield and quality sensitivity to beet stand. In addition, they are planted early and often with an oat cover which may encourage black cutworm egg laying. Cutworms will move to beet seedlings as oats and weeds are killed by herbicides.

CAUTION: Mention of a pesticide or use of a pesticide label is for educational purposes only. Always follow the pesticide label directions attached to the pesticide container you are using. Be sure that the area you wish to treat is listed on the label of the pesticide you intend to use. Remember, the label is the law.

Products are mentioned for illustrative purposes only. We do not endorse or disapprove of any one product.

Anonymous. Black Cutworm. University of Illinois, College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, Extension & Outreach.

Archer, T.L. & Musick, G.L. (1977). Cutting potential of the black cutworm on field corn. Journal of Economic Entomology, 70, 745-747.

Archer, T.L., Musick, G.L. & Murray, R.L. (1980). Influence of temperature and moisture on black cutworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) development and reproduction. Canadian Entomologist, 112, 665-673.

Beck, S.D. (1988). Cold Acclimation of Agrotis ipsilon (Lepidoptera: Nocturidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 81, 964-968.

Busching, M.K. & Turpin, F.T. (1976). Oviposition preferences of black cutworm moths among various crop plants, weeds, and plant debris. Journal of Economic Entomology, 69, 587-590.

Busching, M.K. & Turpin, F.T. (1977). Survival and development of black cutworm (Agrotis ipsilon) larvae on various species of crop plants and weeds. Environmental Entomology, 6, 63-65.

Campinera, J.L., Pelissier, D., Menout, G.S., & Epsky, N.D. (1988). Control of black cutworm with entomogenous nematodes (Nematoda: Steinernematidae, Heterorhabditidae). Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 52, 427-435.

Campinera, J.L. (2012). University of Florida featured creatures.

Carlson, J.D., Whalon, M.E., Landis, D.A., & Gage, S.H. (1992). Springtime weather patterns coincident with long distance migration of potato leafhopper into Michigan. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 59, 183-206.

Domino, R.P., Showers, W.B., Taylor, S.E., & Shaw, R.H. (1983). Spring weather pattern associated with suspected black cutworm moth (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) introduction to Iowa. Environmental Entomology, 12, 1,863-1,871.

Drake, V.A. (1985). Radar observations of moths migrating in a nocturnal low-level jet. Ecological Entomology, 10, 259-265.

Dunbar, M.W., O’Neal, M.E., & Gassmann, A.J. (2016). Increased risk of insect injury to corn following rye cover crop. Journal of Economic Entomology, 109, 1,691-1,697.

Floate, K.D. 2017. Cutworm pests on the Canadian Prairies: Identification and management field guide. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lethbridge, Alberta.

Foster, M.A., & Ruesink, W.G. (1986). Modeling black cutworm-parasitoid-weed interactions in reduced tillage corn. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 16, 13-28.

Hadi, B., Wright, R. Hunt, T., Knodel, J., Glogoza, P., Boetel, M., Whitworth, R.J., Davis, H., & Michaud, J.P. Northern Plains Integrated Pest Management Guide: Cutworms on corn.

He, F., Sun, S., Tan, H., Sun, X., Qin, C., Ji, S., Li, X. Zhang, J., Jiang, X. 2019. Chlorantraniliprole against the black cutworm Agrotis ipsilon (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae): From biochemical/physiological to demographic responses. Sci Rep 9, 10328 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46915-0

Hicks. D.R and S. L. Naeve. (Reviewed 2021.) Corn growers guide to evaluating crop damage and replant decisions, University of Minnesota Extension Publication. Accessed 3/31/21.

Liu YQ, Fu XW, Feng HQ, Liu ZF, Wu KM. 2015. Trans-regional migration of Agrotis ipsilon (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in North-East Asia. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am.. 108:519-527.

Luckmann, W.H., Shaw, T.J., Sherrod, D.W. & Ruesink, W.G. (1976). Developmental rate of the black cutworm. Journal of Economic Entomology, 69, 386-388.

Parisch, T.R., Rodi, A.R., & Clark, R.D. (1988). A case study of the summertime Great Plains low level jet. Monthly Weather Review, 116, 94-105.

Pitchford, K. L., & London, J. (1962). The low level jet as related to nocturnal thunderstorms over Midwest United States. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 1, 43-47.

Santos, L. & Shields, E.J. (1998). Temperature and diet effect on black cutworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) larval development. Journal of Economic Entomology, 91, 267-273.

Sappington, T.W., & Showers, W.B. (1992). Reproductive maturity, mating status, and long-duration flight behavior of Agrotis ipsilon(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and the conceptual misuse of the oogenesis-flight syndrome by entomologists. Environmental Entomology, 21, 677-688.

Sappington, T.W., W.B. Showers, J.J. McNutt, J.L. Bernhardt, J.L. Goodenough, A.J. Kaster, E. Levine, D.G.R. McLeoid, J.F. Robinson, and M.O. Way. (1994). Morpholgical correlates of Migratory Behavior in the black cutworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Environ. Entomol. 23(1) 58-67.

Sherrod, D.W, Shaw, J.T. & Luckmann, W.H. (1979). Concepts on black cutworm field biology in Illinois. Environmental Entomology, 8, 191-195.

Schoenbolm, R. B., & F. T. Turpin. (1978). Parasites reared from black cutworm larvae (Argrotis ipsilon Hufnagel) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) collected in Indiana corn fields from 1947 to 1977. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science, 87, 243-244.

Showers, W.B., Smelser, R.B., Keaster, A.J., Whitford, F., Robinson, J.F., Lopez, J.D., Taylor, S.E. (1989). Recapture of marked black cutworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) males after long-range transport. Environmental Entomology, 18, 447-458.

Showers, W.B., Whitford, F., Smelser, R.B., Keaster, A.J., Robinson, J.F., Lopez, J.D. & Taylor, S.E. (1989). Direct evidence for meteorologically driven long-range dispersal of an economically important moth. Ecology, 70, 987-992.

Showers, W.B., Keaster, A.J., Raulston, J.R., Hendrix III, W.H, Derrick, M.E., McCorcle, M.D., Robinson, J.F., Way, M.O., Wallendorf, M.J. & Goodenough, J.L. (1993). Mechanism of southward migration of a noctuid moth [Agrotis ipsilon (Hufnagel)]: a complete migrant. Ecology, 74, 2,303-2,314.

Showers, W.B. (1997). Migratory ecology of the black cutworm. Annual Review of Entomology, 42, 393-425.

Smelser, R.B., Showers, W.B., Shaw, R.H. & Taylor, S.E. (1991). Atmospheric trajectory analysis to project long-range migration of black cutworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) adults. Journal of Economic Entomology, 84, 879-885.

Story, R.N. & Keaster, A.J. (1982a). The overwintering biology of the black cutworm, Agrotis ipsilon, in field cages (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society, 55, 621-624.

Story, R.N. & A.J. Keaster. (1982b). Temporal and spatial distribution of black cutworms in midwest field crops. Environmental Entomology, 11, 1,019-1,022.

Story, R.N., Keaster, A.J., Showers, W.B. & Shaw, J.T. (1984). Survey and phenology of cutworms (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) infesting field corn in the Midwest. Journal of Economic Entomology, 77, 491-494.

Kaster, L. von. & Showers, W.B. (1982). Evidence of spring immigration and autumn reproductive diapause of the adult black cutworm in Iowa. Environmental Entomology, 11, 306-312.

Wainwright, C.E., Stepanian, P.M. & Horton, K.G. (2016). International Journal of Biometeorology, 60, 1,531-1,542.

Whiteman, C.D, Bian, X. & Zhong, S. (1997). Low-level jet climatology from enhanced rawinsonde observations at a site in the southern Great Plain, 36, 1,363-1,376.

Wu, Y. & Raman, S. (1998). The summertime great plains low level jet and the effect of its origin on moisture transport. Boundary-Layer Meteorology, 88, 445-466.

Zhang, Z., Xu, C., Ding, J., Zhao, Y., Lin, J., Liu, F., Mu, W. 2019. Cynantraniliprole seed treatment efficiency against Agrotis ipsilon (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and residue concentrations in corn plants and soil. Pest Manag Sci 75: 1464-1472.

Zhu, M., Radcliffe, E.B., Ragsdale, D.W., MacRae, I.V., & Seeley, M.W. (2006). Low-level jet streams associated with spring aphid migration and current season spread of potato viruses in the U.S. northern Great Plains. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 138, 192-202.

Reviewed in 2022