Mythimna unipuncta (Haworth, 1809), (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)

Distribution

The armyworm is native to the Americas, but localized invasive populations have been observed in areas of Europe, Africa, the Mideast, and Asia. It is a member of the moth family Noctuidae, a large group that includes most species of cutworms.

In North America, crop damaging infestations are most often observed east of the Rocky Mountains as far north as southern Canada. The highly migratory behavior of the armyworm adults allows them to exploit new geographic areas when weather is suitable. The armyworm cannot survive winters with persistent freezing winter temperatures. In Minnesota, annual infestations are the result of adult moths migrating from wintering areas in the south.

Host range

Armyworm adults feed on plant nectar and are not a threat to crops. The larvae, however, feed primarily on grasses and are an infrequent, but significant, pest of cereals including small grains, corn, rice, forage grasses, and turf grasses. The larvae can feed and complete their development on a wide variety of broadleaf species when large populations deplete their preferred food plants.

Description and life cycle

What is in a name?

The larvae’s behavior of congregating and moving in large groups when looking for new food sources is the basis for the name armyworm. The caterpillars of several other insect species display similar group behavior.

Most species that include armyworm in the common name belong to the Noctuidae family. One example is the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda), an infrequent late-season migrant visitor to Minnesota from the tropics.

Some Minnesotans also call the eastern forest tent caterpillars (Malacosoma americanum) that create communal webbed shelters (tents) and feed on the leaves of broadleaf trees and shrubs “armyworms.” However, these moths belong to the insect family Lasiocampidae and are not related to Mythimna unipuncta.

To avoid confusion with other species that have armyworm as part of their approved common name or are regionally known as “armyworms,” Mythimna unipuncta is often referred to as “true armyworm.”

Adult

The armyworm is a moderately sized moth with a wingspan of approximately 1½ inches.

On specimens in good shape, the forewing is tan to reddish-brown with a small white mark in the center. The species name “unipuncta” is based on this single white point.

A faint diagonal line of small black dots extends to the tip on the forewing’s outside (away from the body when spread).

The hindwings are pale to dark gray with a light outer border (Figure 1).

As moths age, or wing scales are otherwise damaged, these identifying marks are lost and identification becomes more difficult.

The armyworm moths are nocturnal and, like many insects, are attracted to light. Receptive females release a sex pheromone to attract mates.

Egg

The female moth seeks out areas of lush forage grasses, small grains, or grassy weeds. She deposits her eggs in compact masses of one to several rows that hold a few to more than 200 white to yellowish eggs, which darken prior to hatching. The eggs are concealed between the blades and stems of grasses and the folds of leaves. Over several days, a single female has been observed to produce over 1800 eggs.

The armyworm’s rate of development depends on temperature. The eggs have been reported to hatch in as few as three days at 84°F and an average four days at 77°F. The eggs are the most cold-tolerant immature life stage. Egg hatch is greatly slowed at temperatures below 55°F, with no hatch occurring below 41°F.

Larva

The caterpillar is the crop-damaging insect stage. Armyworms have three pairs of claw-like true legs near the head and five pairs of fleshy ‘prolegs’ along the abdomen (four pairs of abdominal prolegs and one pair of rear anal prolegs) (Figure 2).

The larvae need to molt to larger exoskeletons as they grow and typically pass through six larval stages (instars). The first instar larvae are pale with dark heads. The first set of prolegs is shorter than others during the first- and second- instar causing the larva to have a “looping” gait, arching their back when walking.

A larva’s length and head capsule width can be used to estimate its age. Approximate larval sizes from a Tennessee population are shown in Table 1, although larval size can be highly variable base on temperature and available food.

Table 1. Mean armyworm larval measurements (after Breeland, 1958).

| Instar | Body length (mm) | Head capsule width (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.8 | 0.35 |

| 2 | 1.8 | 0.57 |

| 3 | 7 | 0.94 |

| 4 | 11 | 1.5 |

| 5 | 18-20 | 2.3 |

| 6 | 30-35 | 3.0-3.5 |

Overall, late-instar caterpillars can range from tan and olive to nearly black in color. The pattern of a longitudinal dark band flanked by white-bordered pink to orange bands along the side is a distinguishing characteristic on the older larvae, as is the net-like pattern on the head and a dark band at the base of the abdominal prolegs (Figure 2). Full-grown larvae are approximately 1-3/8 inches long. The larvae are mostly active at night.

A Canadian study found that larvae were only able to complete development at temperatures above 50°F. Between 50 and 84°F, armyworms developed and matured faster as temperature increases. However, larvae took longer to develop, and survival of older larvae decreased at 88°F a temperature near the upper developmental threshold. Larval development from egg hatch to pupa was completed in 16 to 87 days at 84°F and 55°F, respectively with the length of the larval stage, averaging 26 days at 77°F. At cooler temperatures, or when food is inadequate, larvae may undergo one or more additional instars, prolonging development.

Multiple or extended egg-laying and the varied microclimates within the field can lead to a wide range in larval development (Figure 3).

Armyworms do not have a fixed diapause (a life stage where development is suspended to survive adverse environments). Therefore, no life stage can survive in Minnesota or other states with persistent sub-freezing winter temperatures.

Further south, in latitudes such as Tennessee and Kentucky, mild winters allow the armyworm to overwinter as an immature larva. Adding instars allows the overwintering larva to delay maturity until conditions are more favorable. In frost-free areas such as Florida, the insect is active and breeds year-round.

Pupa

The larva stops feeding for a day or two and forms a web-lined pupal cell in the top inch of soil. There is no cocoon, and the moths emerge from the reddish-brown pupa in one to three weeks. The different developmental stages can be roughly predicted using a degree-day (DD) model with a base temperature of 50°F. It requires approximately 340 DD to reach the end of larval feeding and 575 DD to complete one life cycle from egg to adult. The average duration of each life stage is shown in Table 2.

In the northern part of its range, the armyworm life cycle from egg to adult takes 35–60 days. Multiple generations, usually two to three in Minnesota, are produced until the insects are killed by cold temperatures or environmental conditions trigger a southward migration of adults.

Table 2. Armyworm life table.

| Life stage | Avg days / life stage1 |

Corn foliage consumption (mg)2 |

Percent of total foliage consumption2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADULT (female) | |||

| Egg-laying | 8.7 | ||

| Total | 17.2 | ||

| EGG | 7.5 | ||

| Larva | |||

| 1st instar | 4.8 | 1 | 0.1 |

| 2nd instar | 3.3 | 1.5 | 0.2 |

| 3rd instar | 3.3 | 6 | 1.2 |

| 4th instar | 3.8 | 21 | 4.2 |

| 5th instar | 4.4 | 75 | 14.9 |

| 6th instar | 10.3 | 400 | 79.3 |

| Total larva | 29.9 | ||

| PUPA | 18.3 | ||

| TOTAL | 72.9 | 504.5 | 100.0 |

1After Guppy, J.C. 1951. Three-year average in an Ontario, Canada environment (1957-1959).

2Adapted from Mukerji, M.K. and J.C. Guppy (1970) Estimated individual instar values determined from measurement of the manuscript's graphic data.

Crop damage

Armyworm outbreaks occur infrequently but can be very destructive when they do.

The first instar larvae are phototrophic and may feed during the day or the night. The larvae’s chewing mouthparts skeletonize plant tissues on the tips of younger leaves or beneath leaf sheaths. When resting they shelter in leaf sheaths or in stubble.

The late second instar and older larvae chew holes and notches through the leaf from the edge of the leaf blade toward the midrib and may feed anywhere on the plant. Older larvae avoid light, hiding during the day in stubble, under leaves or soil clumps near the base of the plant, or in the whorls of larger corn. Large larvae are often found on the ground and under lodged small grains and grasses. From dusk to dawn, and on dreary, cloudy days, the larvae will move higher on the plant to feed. Third to sixth-instar larvae curl into a C-shape when disturbed.

The larvae are voracious feeders. Most of the foliage is consumed by the last instar (Table 2). The presence of the insect and its feeding often goes unnoticed until large populations defoliate a field or a field or pasture overnight. After a large armyworm infestation moves through a field of whorl-stage corn, only stalks and leaf mid ribs may remain (Figure 4). Young corn and small grains may be completely defoliated (Figures 7-10).

The larvae may clip the seed heads of cereals and forage grasses in addition to feeding on leaves. Once a food source has been depleted, the larvae will move n masse to find new feeding areas (Figure 11).

Crops and forages are often damaged by larva moving from grasses within fields, field borders, and from adjacent crops. When hungry armyworms attack broadleaf crops, it is most often after grassy weeds or cover crops have been consumed or killed by herbicide.

In Minnesota, most of the damaging late-instar larvae populations occur in mid-June to mid-July. It typically takes 30-40 days from moth flight and egg-laying to the beginning of the sixth and most destructive larval instar.

Natural enemies

Most years, armyworm populations are kept in check by natural enemies. The small, white eggs of a parasitic tachinid fly are often found attached near the head of caterpillars (Figure 5). A range of fly, wasp, and nematode parasites have been isolated from armyworm eggs, larvae, and pupae.

Armyworm larvae can also be infected by viral, fungal and bacterial pathogens and the diseased larvae often appear less active or flaccid. Make note of any diseased or parasitized larvae while scouting. They could signal the start of a rapid armyworm population collapse.

Bird, mammal, and insect predators (notably ground beetles) also reduce larval populations. The presence of large numbers of birds (blackbirds in particular) early in the morning or in the evening can indicate an armyworm infestation in the field. Birds and bats prey on adults. Noctuid moths have evolved behaviors to avoid the high frequency echolocation of bats.

Armyworm moth migration

Lab experiments found no life stage of the armyworm able to survive two weeks of freezing temperatures. Historical observations reinforce that armyworms cannot overwinter in Minnesota and each year’s infestations originate in areas to our south.

Long-distance migration is an active behavior on the part of the insect. Moths use environmental and visual cues to begin migration, orient in flight, and terminate migration. Armyworm moths can move short distances north on their own, but can take advantage of weather systems using low-level jet streams to quickly cover long distances.

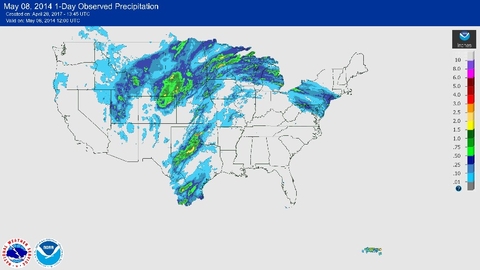

In the North American plains, the Rocky Mountains to the west of the Great Plains and warm Gulf of Mexico waters provide the energy for these long-distance transport systems. Cool, dry, low pressure in the western plains interacts with warm, moist, high pressure systems in the eastern plains to create strong southerly winds that are especially strong at night (Figure 6).

Moths migrating from the overwintering areas fly upward at dusk. With cooperative weather systems, surface winds and updrafts in advance of thunderstorms pull the moths into the low-level jet stream. These winds are strongest at night, moving at 30 to 80 miles per hour, and can occur from about 330 to 3,000 feet in altitude.

The flight is mostly passive with moths carried along until they decide to “drop out”, encounter cold air, or rain out in thunderstorms, arriving in the north in excellent shape. A high pressure center to the east with a strong low pressure system approaching from the west produces strong, persistent southerly winds that can bring armyworm moths northward to Minnesota.

Two ingredients are necessary for spring long-distance migrant moths to arrive in Minnesota. First, the air reaching Minnesota must have passed through the overwintering areas when migrating adults are present.

Second, the track of the low-pressure center is critical. If the low tracks too far south, migration is cut off south of Minnesota. If the low tracks through Minnesota or northern Iowa, we have the potential for moths to reach Minnesota.

These weather systems may stall with the frontal boundary cutting across Minnesota. In that case, moth deposition is often heavy south and east of the front. Moths often drop out on the edges of heavy rainfall. Several low-pressure systems may ripple across the moist air moving and compound the moth deposition in Minnesota.

Radar studies in the 1980s found most evening migrating insects move at an altitude of 1,700 feet or so. Wind trajectories can be used to estimate where an immigration event might have originated.

Not all Minnesota’s armyworms are destined to freeze to death in the fall. Armyworm migration south in the late summer and fall can be assisted by southerly flows associated with cold fronts.

Armyworms are not tolerant of hot temperatures and populations are low in southern states during the heat of summer. Migration allows the armyworm to avoid both high summer temperatures in the southern wintering areas and the freezing winter temperatures in the northern part of their range. Hydrogen and carbon isotopes in armyworm wing chitin (a polysaccharide in insect exoskelotons) were used to trace moths captured in Texas much further north into Ontario, Canada, in the spring and back south again in the fall.

Armyworm outbreaks are often worse in cool, wet conditions. This may reflect optimal temperatures for the insect, but those same environmental conditions also favor lush dense growth of small grains and cool-season forage grasses. It may also reflect multiple weather systems bringing moisture and insects from the south.

Early planted small grains tend to be more dense and taller. This creates a more attractive habitat for egg-laying moths. Dense stands of grasses provide protection for the larvae, as do lodged small grains or cool season forage grasses. These are often areas where larvae congregate and eventually move from as they deplete their food.

Areas with dense grass weeds within the field may be attractive to egg-laying moths. Overwintered cereal rye cover crops also may harbor small armyworms. Hungry larvae can move to the crop when weeds or cover crop is terminated.

The presence of a large migration flight of true armyworm into Minnesota can be detected with black light traps. These moth captures can predict if a problem is likely and when it will occur. It's more difficult to know where the problem will occur due to the possibility of immigrant moths re-migrating. Historically, if a blacklight trap captures near or above sixty moths in a single night, it has been an indicator that an armyworm problem will occur somewhere in Minnesota within a few weeks.

Like blacklight traps, some non-specific feeding attractants can capture both sexes of armyworm and other moths. However, pheromone traps for true armyworm are commercially available to detect moth flights. They are relatively inexpensive and easily deployed. The pheromone traps, for the most part, only capture unmated armyworm male moths. The numbers of moths captured tend to be small and the capture period short compared to blacklight traps. Qualitatively, they can indicate a moth flight has occurred. Quantitatively, it is unclear how pheromone captures relate to crop damage.

While both black light and pheromone traps can indicate when a moth flight has occurred and perhaps the relative size of the flight, scouting for larvae remains the best way to determine the risk of armyworm damage to a crop. In a year when armyworm larvae are abundant, finding the first economically threatening armyworm populations early can help encourage scouting efforts and prevent armyworm defoliated fields.

Scouting and economic thresholds

The mere mention of armyworms can cause angst in those who have experienced outbreaks, and the news of armyworms in the area can trigger unnecessary insecticide applications. Fortunately, other than taking some time, scouting for armyworms is straightforward and they have been easily controlled with insecticides.

Lush grasses are preferred egg laying sites for the armyworm moth. Lodged areas of small grains, grasses or the grass borders of corn and small grain fields should receive special attention when scouting. When they have defoliated an area, larvae will move from field borders or between fields.

Focus your efforts on high-risk areas first. Armyworms prefer to feed on the most tender foliage. Leaves with feeding damage and the presence of frass (insect fecal pellets) on plants and on the ground (Figure 7) indicate that an insect was present, but the presence of live larvae indicates the potential for future damage exists. Finding mostly large, last instar larvae, particularly if pupae are found beneath the soil surface, is an indication that the feeding is ending.

Armyworm larvae are most active at night and on cloudy days. During the heat and bright sunlight of day, larvae often hide under leaf litter or soil clods on the ground and scouting is often more effective near dawn and dusk and on cloudy days. When disturbed, armyworms drop to the ground and curl into a C-shape to “play possum.” Preliminary scouting for armyworms in small grains, field edges, forage grasses, and even grassy areas within row crops can be done with a sweep net. Once armyworms are found, switch to a crop specific scouting method.

Corn

Grassy weeds are attractive to egg-laying moths. When scouting, pay close attention to field borders and within-field areas with current or past high grass weed pressure (Figure 8). If not killed before moths arrive, grass cover crops or winter rye may also be attractive egg laying sites.

Examine plants for feeding damage and larvae. On larger plants, the larvae can often be found in the whorl, where the nighttime feeding often occurs (Figure 9). When there are large amounts of plant residue (cover crop, dead weeds, etc.) larvae may hide on the ground. Small corn (5 leaves or less) can typically recover from armyworm defoliation.

Economic threshold

Treat whorl stage corn when 25% of plants have two larvae/plant or 75% of plants have one larva or more. On tassel stage corn, focus on minimizing defoliation at or above the ear leaf.

Wheat, barley and oats

Some studies indicate a difference in preference among the small grain species, but all are hosts. When trying to detect larval populations, pay close attention to early planted, taller fields and to areas that are lodged, are near lodged grass borders, or have grassy weeds. When an economic armyworm infestation is suspected in a small grain field, populations per square foot should be estimated.

Head clipping is a behavioral change and usually occurs after leaves have been defoliated or senesce.

Economic threshold

Shake the plants and look for larvae on the ground in a square foot area. In small grains the treatment threshold is 4-5 larvae/square foot. Check under debris and soil clods. Do this in at least five locations within the field.

Pastures and forage grasses

The same scouting methods and economic thresholds described for small grains can be used for pastures, forage grasses and grass seed production fields.

What about other crops?

Despite their strong preference for grasses, armyworms may be forced to feed on less preferred hosts. Armyworms may clean out the weedy grasses while leaving a less desirable broadleaf crop alone but on occasion, starving armyworms will switch to the broadleaf crop when the grass food source has been eaten or killed. When terminating a grass cover crop in corn, sugarbeets, newly seeding alfalfa, or other crops, it is worth looking for armyworm larvae based on feeding or sweep net samples. The same applies to areas of dense grassy weeds. Removing their food source will force the armyworms to feed on the crop or move to a nearby field.

Treatment for armyworm

Bt hybrids

Only Bt corn hybrids containing the Vip3a protein (Viptera), alone or in stacks, are labeled for controlling armyworm. In addition to lush small grain and forage grasses, grassy spring weeds and cover crop growth, the Bt protein in the planted hybrid can help prioritize fields for scouting. The Handy Bt corn trait table shows which Bt proteins control armyworm and several other insect species.

Insecticides

High rates of neonicotinoid seed treatments (e.g., Poncho, Cruiser, Gaucho) are effective on many seed and seedling insects and may provide some early seedling protection against armyworm. Seed applied insecticides containing a diamide (e. g. chlorantraniliprole and cyantraniliprole) may show increased control of armyworm.

Fortunately, armyworms can be controlled effectively with a timely application of a rescue, foliar insecticide. Many post-plant insecticide products provide effective control of armyworm with products in the pyrethroid, organophosphate, carbamate and diamide insecticide groups.

Do not base treatment decisions solely on field-edge populations. The presence of live armyworm larvae should be confirmed before an insecticide is applied to a field. Insecticide treatment of populations that are starting to pupate or are heavily parasitized is not likely to provide economic benefit. Long insecticide residuals are generally not needed because of the short time a larval generation is damaging. Refer to the insecticide label for rates.

Spot treatments can be effective when combined with careful scouting. Partial field or border insecticide treatments for armyworm are often sufficient when infestations are well identified by scouting early or when armyworms populations are migrating (Figure 11). Treat several boom widths ahead of the infestation.

Most insecticides have little activity on armyworm eggs. Moth migration occurring over a long period of time and a prolonged egg-laying period increases the difficulty of timing the insecticide. Applying too late risks economic crop loss and too early allows late-hatching larvae to escape.

During daylight hours, armyworms spend much of their time hiding low in the canopy and under lodged plants so good insecticide coverage is important. Use appropriate water volumes and pressures matched spray nozzles suited to insecticide application. Do not use reduced rates, particularly when large armyworms are the target. Spraying in the evening may help control but could also expose insecticides to temperature inversions and drift, reducing effectiveness.

There have been recent reports of issues with performance pyrethroid insecticides against armyworm. However, pyrethroid insecticide resistance has not been documented in armyworm. These issues might have been related to coverage, environmental conditions, short insecticide residual, missing late-hatching larvae, and applications made too late to non-feeding prepupal larvae.

Important insecticide application notes

It is particularly important to check the pre-harvest interval of any small grain or forage pesticide. In corn, take precautions to protect pollinators, particularly if corn is nearing the tassel stage.

Scouting and rescue insecticide applications are the best defense against yield loss from armyworms. Before deciding to treat, make sure cutworms are still present and actively feeding.

Cultural control

Maintaining good, early season weed control and avoiding late termination of grass cover crops can reduce the attractiveness of fields to egg-laying moths.

True armyworm lookalikes in corn, cereal crops and forage grasses

Be aware that there can be an armyworm imposter lurking on field edges.

Grass sawfly larvae range from tan to green. They are in the order Hymenoptera (bees and wasps) rather than Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths).

The fleshy prolegs are a giveaway, because they number more than five. In the Lepidoptera, the prolegs number 5 or less. Lepidoptera caterpillar prolegs have minute hooks (crochets) while those of sawflies do not (Figures 12, 13).

Sawflies can clip small grain heads. Minnesota infestations heavy enough to require treating have not occurred in recent memory.

Grass sawfly larvae are mostly found in the grassy borders of fields.

The wheat head armyworm, Dargida diffusa (Walker, 1856), is another moth also in the noctuid family. The adults are similar in appearance to the true armyworm, but have a dark streak the length of the forewing. They are captured in Minnesota light traps and can be mistaken for true armyworm. They are believed to overwinter as pupae in the soil.

They are gray to green with a broad pale lateral stripe. They are slenderer and have a proportionally larger head than the true armyworm (Figure 14). They feed on the heads and seeds of cereals and other grasses but are rarely a pest of cereal crops in Minnesota.

Another look alike moth is the lesser wainscot moth Mythimna oxygala (Grote, 1881), whose larvae also feed on grasses. The larvae are similar to the armyworm but the prolegs lack the black band.

Some moths in the genus Leucania (Ochsenheimer, 1816) are also similar in appearance to armyworm and can cause confusion in interpreting trap captures.

Several species of cutworms may be found in corn and small grain crops. Anticipate increased populations of other migratory and overwintering cutworm species in weedy fields or fields with a cover crop.

CAUTION: Mention of a pesticide or use of a pesticide label is for educational purposes only. Always follow the pesticide label directions attached to the pesticide container you are using. Be sure that the area you wish to treat is listed on the label of the pesticide you intend to use. Remember, the label is the law.

Ayre G.L. 1985. Cold tolerance of Pseudaletia unipuncta and Peridroma saucia (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Can. Entomol. 117(8):1055-1060. doi:10.4039/Ent1171055-8

Batallas, R.E., Rossato, J.A., Mori, B.A., Beres, B.L. and Evenden, M.L. 2020. Influence of crop variety and fertilization on oviposition preference and larval performance of a generalist herbivore, the true armyworm, Mythimna unipuncta. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 168: 266-278. https://doi.org/10.1111/eea.12894

Breeland, S. G. "The Armyworm, Pseudaletia unipuncta (Haworth), and Its Natural Enemies. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1957. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2956 (Accessed 3/24/21)

Breeland, S.G. 1958. Biological studies on the armyworm, Pseudaletia unipuncta (Haworth) in Tennessee (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Journal of the Tennessee Academy of Science, 33:263-347.

Brou , V. A., Jr., and C. D. Brou. 2020. Mythimna unipuncta (Haworth, 1809) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Louisiana. South. Lepid. News 42: 31-33.

CABI Invasive species compendium . Datasheet: Mythimna unipuncta (rice armyworm). https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/45094#tosummaryOfInvasiveness (Accessed 3/24/2021)

Carscallen, G.E., S. V. Kher, M. L .Evenden, 2019. Efficacy of Chlorantraniliprole Seed Treatments Against Armyworm (Mythimna unipuncta [Lepidoptera: Noctuidae]) Larvae on Corn (Zea mays). J. Econ. Entomol. 112 (1): 188–195. https://doi.org/10.1093

CIE, 1967. Distribution Maps of Plant Pests, No. 231. Wallingford, UK: CAB International.

Difonzo, C. 2021. The handy Bt trait table for U.S. Corn Production. https://agrilife.org/lubbock/files/2021/02/BtTraitTable_Feb_2021B.pdf (Accessed 4/06/21)

Dunbar, M.W., M.E. O’Neal, and A.J. Gassmann. 2016. Increased risk of insect injury to corn following rye cover crop. Econ Entomol 109(4) 1691-1697

Fenton M.B. and Fullard J.H. 1981. Moth hearing and the feeding strategies of bats. Am Sci: 69: 266-275.

Fields, P.G. and J.N. McNeil. 1984. The overwintering potential of true armyworm, Pseudaletia unipuncta (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), populations in Quebec. Can. Entomol. 116(12):1647-1652. doi:10.4039/Ent1161647-12

Guppy J.C. 1961. Life history and behaviour of the armyworm, Pseudaletia unipuncta (Haw.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in eastern Ontario. Can. Entomol. 93:1141-1153.

Guppy, J.C. 1967. Insect parasites of the armyworm, Pseudaletia unipuncta (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), with notes on species observed in Ontario. Can. Entomol. 99:94-106.

Guppy, J.C. 1969. Some effects of temperature on the immature stages of the armyworm, Pseudaletia unipuncta (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), under controlled conditions. Can. Entomol. 101: 1320-1327.

Harvey, J. and Y. Tanada. 1985. Characterization of the DNAs of 5 baculoviruses pathogenic for the armyworm, Pseudaletia unipuncta. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 46(2):174-179

Hobson, K..A., K. Doward, K.J. Kardynal, and J.N. McNeil. 2018. Inferring origins of migrating insects using isoscapes: a case study using the true armyworm, Mythimna unipuncta, in North America. Ecol. Entomol. 43: 332-341. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12505

Landolt, P.J. and B.S. Higbee. 2002. Both sexes of the true armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) trapped with the feeding attractant composed of acetic acid and 3-methyl-1-butanol. Fla. Entomol. 85(1):182-185.

Laub, C.A. and J.M. Luna. 1992. Winter cover crop suppression practices and natural enemies of armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in no-till corn. Environ. Entomol. 21(1):41-49

López, C., P. Muñoz, M. Pérez‐Hedo, M. Moralejo, and M. Eizaguirre. 2017. How do caterpillars cope with xenobiotics? The case of Mythimna unipuncta, a species with low susceptibility to Bt. Ann Appl Biol, 171: 364-375. https://doi.org/10.1111/aab.12380

McNeil, J.N. The True Armyworm, Pseudaletia Unipuncta: A Victim of the Pied Piper or a Seasonal Migrant?. Int. J. Trop. Insect. Sci. 8: 591–597 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742758400022657

Marcovitch S, 1958. Some climatic relations of armyworm outbreaks. J Tenn Acad Sci 33:348-350.

Marino, P.C., and D. .A. Landis 1996. Effect of Landscape Structure on Parasitoid Diversity and Parasitism in Agroecosystems. Ecol Appl 6: 276-284. https://doi.org/10.2307/2269571

Mukerji, M.K., and.C. Guppy. 1970. A quantitative study of food consumption and growth in Pseudaletia unipuncta. Can. Emtomol. 102: 1179-1188

Mulder P.G. and W.B. Showers.1986. Defoliation by the armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on field corn in Iowa. J. Econ. Entomol. 79(2):368-373

Reynolds, A.M., D.R. Reynolds, S.P.,Sane, G. Hu, J.W. Chapman. 2016 Orientation in high-flying migrant insects in relation to flows: mechanisms and strategies.Phil.Trans. R. Soc. B371: 20150392.http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0392

Schaafsma, A. W., Holmes, M., Whistlecraft, J. and Dudley, S. A. 2007. Effectiveness of three Bt corn events against feedingdamage by the true armyworm (Pseudaletia unipunctaHaworth). Can. J. Plant Sci. 87: 599–603.

Steck, W.F., E.W. Underhill, B.K. Bailey and M.D. Chisolm.1982 A 4-component sex attractant for male moths of the armyworm, Pseudaletia unipuncta. Ent. Exp. & appl. 32:202-304

Steinkraus, D.C., and A.J. Mueller. 2003. Impact of true armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) feeding on wheat yields in Arkansas. J. Entomol. Sci. 38(3):431-438. doi: https://doi.org/10.18474/0749-8004-38.3.431

Taylor, P. S. and E. J. Shields. 1990. Development of the armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) under fluctuating daily temperature regimes, Environ Entomol. 19 (5): 1422–1431, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/19.5.1422

Turgeon, J.J. and J.N. McNeil . 1983. Modifications in the calling behaviour of Pseudaletia unipuncta (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), induced by temperature conditions during pupal and adult development. Can. Entomol. 115(8):1015-1022. doi:10.4039/Ent1151015-8

Turgeon, J.J., J.N. McNeil, and W.L. Roelofs.1983. Field testing of various parameters for the development of a pheromone-based monitoring system for the armyworm, Pseudaletia unipuncta (Haworth) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Environl Entomol 12(3):891-894. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/12.3.891

Varenhorst, A. J., M. W. Dunbar, and E. W. Hodgson. 2015. True armyworms defoliating corn seedlings. Integrated Crop Management News, Iowa State University, Ames, IA. (http://crops.extension.iastate.edu/cropnews/2015/05/true-armyworms-defoliating-corn-seedlings) (accessed 26 March 2021)

Willson, H. R., and J. B. Eisley. 1992. Effects of tillage and prior crop on the incidence of five key pests on Ohio corn. J. Econ. Entomol. 85: 853–859.

Reviewed in 2021