Rolling soybeans: The good, the bad and the injured

Land rolling has become a common soil-finishing practice for soybean in Minnesota and throughout the Upper Midwest.

The practice has been used for decades in alfalfa and grass seed production to improve germination and manage rocks, but it’s relatively new for row crops, where its main purpose is to improve harvesting efficiency and reduce combine damage.

Large rolling drums are pulled across the soil in the spring, usually right before or after planting (Figure 1). According to Iowa State University, the drums exert a packing force of about 3 pounds per square inch, similar to the pressure exerted by planter closing wheels.

Advantages

Land rolling prepares the field for harvesting by pushing small and medium-sized rocks down into the soil and crushing soil clods and corn rootballs. This allows the combine head to be set low to the ground, reducing the risk of picking up damaging rocks, rootballs and soil.

Other benefits of soybean rolling include:

Reduced operator fatigue

Less downtime

Less wear and tear on harvesting equipment

Faster combine speed

Cleaner seed at harvest

Disadvantages

Land rolling does pose agronomic, economic and environmental concerns. These include:

Potential plant injury

Soil sealing

Erosion

The loosening of corn stalks

Added expense

Understanding the advantages and disadvantages of land rolling will help farmers decide if and when rolling makes sense.

Land rolling and its impact

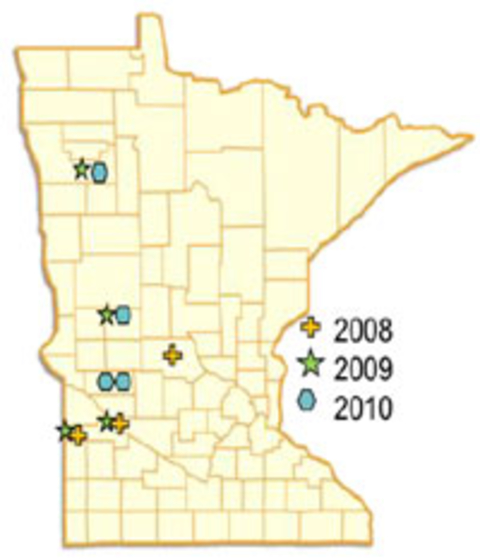

To better understand land rolling, the University of Minnesota Extension conducted a three-year research study (Figure 2) to assess their impact and inform best practices for Minnesota soybean producers.

Researchers carried out the Extension trials at 10 sites in northwest and west-central Minnesota (Figure 2). Rolling was done from 2008 to 2010 at:

Pre-plant

Post-plant

50 percent emerged

First trifoliate (V1)

Third trifoliate (V3)

No rolling

After the treatments, researchers collected the following data:

Water infiltration and runoff

Plant population

Plant injury

Yield

Seed quality characteristics (protein, oil, moisture and test weight)

The Extension trials – which were sponsored by the Minnesota Soybean Growers – found no significant differences in stand, average yield or seed quality among the treatments. The study also concluded that soybeans may safely be rolled up to the third trifoliate growth stage, or V3, when soybean plants are about 4 to 6 inches tall.

Land rollers range in size from 20 to 85 feet wide and have 2- to 3.5-foot diameters. Models are available with a single drum or several independently suspended sections. There are many types of land rollers, some with smooth drums and others with notched or coil-type drums.

The University of Minnesota Extension research study (Figure 2) used several styles of land rollers on farmers’ fields. These included:

- A coil packer (Figure 3), which breaks up rootballs, leaving a rougher soil surface but doesn’t push down rocks.

- A notched roller (Figure 4), which pushes down rocks, breaks up corn rootballs and leaves a rough soil surface.

- A smooth roller (Figure 5), which breaks up corn rootballs and pushes down rocks, but leaves a very smooth soil surface.

Trials found no significant difference in yield between the different rollers.

One of the most practical questions for farmers pertains to how late they can roll soybeans without cutting into yield. Rolling is usually done immediately before or after planting, but delays for wet weather or spring workload are common.

In general, wheel tracks cause more plant damage to emerged soybeans than the rollers themselves. In the Extension trials, soybeans rolled at V3 suffered significant plant damage at two of the four research sites in 2010 (Table 1, Figure 6).

However, greater plant damage didn’t always reduce yields. Take caution in wet years, when stem injuries caused by rolling could make plants more susceptible to soil-borne diseases. At two sites, rolling at V3 increased goose-necking and lodging.

Table 1: Impact on plant population and injury when soybeans were rolled at different stages

| Treatment | Average population: 2009 | Average population: 2010 | Plants injured: 2009 | Plants injured: 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-plant | 158,000 plants per acre | 160,000 plants per acre | -- | -- |

| Post-plant | 158,000 plants per acre | 160,000 plants per acre | -- | -- |

| 50% emergence | 152,000 plants per acre | 142,000 plants per acre | 6.6% | 1.1% |

| First trifoliate | 153,000 plants per acre | 151,000 plants per acre | 11.6% | 4.0% |

| Third trifoliate | 150,000 plants per acre | 135,000 plants per acre | 16.4% | 8.2+% |

| No rolling | 155,000 plants per acre | 154,000 plants per acre | -- | -- |

| LSD (0.05) | No significant statistical difference | No significant statistical difference | 2.2% | +In 2010, two of the four sites had significantly greater damage with the V3 treatment. |

Extension trials found that rolling soybean at or before the third trifoliate (V3) stage produced no significant yield or seed quality advantage to offset the cost of the operation (Table 2).

Rolling at or after V3 isn’t recommended because of the increased potential to injure plants that could reduce yield under wetter growing conditions that weren’t observed in these studies.

Table 2: Yield when rolling soybean at different stages in Minnesota

| Treatment | 2008: Average yield | 2009: Average yield | 2010: Average yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-plant | 35.8 bushels per acre | 46.6 bushels per acre | 52.1 bushels per acre |

| Post-plant | 35.1 bushels per acre | 46.6 bushels per acre | 51.2 bushels per acre |

| 50% emergence | 36.5 bushels per acre | 46.1 bushels per acre | 51.8 bushels per acre |

| First trifoliate | -- | 45.2 bushels per acre | 51.6 bushels per acre |

| Third trifoliate | -- | 45.3 bushels per acre | 50.0 bushels per acre |

| No rolling | 36.6 bushels per acre | 44.7 bushels per acre | 51.8 bushels per acre |

| LSD (0.05) | No significant statistical difference | No significant statistical difference | No significant statistical difference |

Trials in other states

The Minnesota project was modeled after initial research conducted by North Dakota State University from 2003 to 2004. Iowa also conducted a two-year soybean-rolling research study initiated in 2009 (Table 3).

All three efforts concluded that soybean can safely be rolled until the V3 stage without significantly affecting yield. In the Iowa trials, rolling at the sixth trifoliate stage caused severe plant damage and significantly reduced soybean yield by almost 10 bushels per acre.

Table 3: Yield when rolling soybean at different stages

| Treatment | 2003: Average yield in North Dakota | 2004: Average yield in North Dakota | 2009: Average yield in northwest Iowa | 2010: Average yield in northwest Iowa | 2010: Average yield in north-central Iowa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-plant | 30.9 bushels per acre | 19.7 bushels per acre | 64.2 bushels per acre | 58.8 bushels per acre | 57.4 bushels per acre |

| 50% emerged | 28.7 bushels per acre | 21.4 bushels per acre | -- | -- | -- |

| First trifoliate | 30.8 bushels per acre | 23.4 bushels per acre | 65.5 bushels per acre | 58.2 bushels per acre | 58.3 bushels per acre |

| Third trifoliate | -- | 24.7 bushels per acre | -- | -- | 55.7 bushels per acre |

| Sixth trifoliate | -- | -- | -- | -- | 49.4* bushels per acre |

| No rolling | 29.2 bushels per acre | 23.4 bushels per acre | 64.7 bushels per acre | 59.8 bushels per acre | 58.1 bushels per acre |

| LSD (0.05) | No significant difference | No significant difference | No significant difference | No significant difference | 5.9 bushels per acre |

*Yield at this treatment is significantly different than other treatments.

One advantage to rolling residue is the flattening of stalks and breaking apart corn rootballs (Figure 7).

Breaking apart residue and pushing it into the soil may help to speed up microbial decomposition. This could be used as a way to manage tough-to-break-down residue, especially in a reduced tillage system.

Another added benefit to having moderate residue levels is its ability to protect emerging soybean plants from roller damage at later growth stages (Figure 8).

Residue can support some of the roller’s weight, protecting the emerging cotyledon. When rolling after emergence, residue acts as a cushion to keep the plant from possibly bending to the breaking point when rolled.

Disadvantages

The most serious environmental disadvantage of rolling is its effect on surface soil structure. Rolling crushes surface soil aggregates, increasing the potential for soil sealing, runoff and erosion.

For example, in 2008, a hard rain about the time of emergence caused ponding on rolled research plots in Canby in southwestern Minnesota, resulting in a 95 percent reduction in stand (Figure 9). The problem was less severe on non-rolled plots, resulting in only a 46 percen

To minimize this problem, leave approximately 40 percent residue on the field to protect the otherwise exposed soil.

Water infiltration

Standing water between the rows of rolled plots after moderate to heavy rains has been observed in northern Iowa fields. This suggests water infiltration may be slower in rolled fields.

Reduced infiltration leads to more surface runoff after rainfall, and contributes to soil and nutrient losses and water pollution.

In 2011, Iowa State University compared water infiltration in rolled and unrolled fields soon after rolling. Infiltration measurements were taken on Canisteo silty clay loam, Clarion loam and Webster silty clay loam soils at four sites in northern Iowa.

Although there was considerable variability, infiltration rates were generally lower in the rolled plots (Table 4). However, the differences weren’t statistically significant, except on the poorly drained Webster silty clay loam soil. The researchers concluded that land-rolling reduces water infiltration in poorly drained soils.

Rolling also increases the risk of both wind and water erosion, especially on susceptible soils or sloping terrain. After rolling, residue may come loose from the soil, reducing the soil conservation benefits of less tillage.

There are many reported instances of blowing soil and residue after rolling (Figure 10). In parts of Minnesota, blowing corn residue after rolling can become a significant nuisance in fence lines, windbreaks and road ditches.

Table 4: The impact of rolling on water infiltration rates

| Soil type | Infiltration rate: Unrolled | Infiltration rate: Rolled | Infiltration rate: Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canisteo silty clay loam | 2.6 inches per hour | 1.7 inches per hour | NS |

| Clarion loam | 1.2 inches per hour | 2.8 inches per hour | NS |

| Canisteo silty clay loam | 2.4 inches per hour | 2.8 inches per hour | NS |

| Webster silty clay loam | 6.4 inches per hour | 1.2 inches per hour | * |

*NS means no significant statistical difference between treatments.

In 2012, roller rental expenses in Minnesota ranged from $3 per acre to $5 per acre, plus fuel and labor. Custom rates range from $4 per acre to $12.50 per acre, with an average cost of $7.25 per acre, according to Iowa State University's 2012 custom rates survey.

Land roller prices depend on the size of the implement, and range from $17,000 for a 20-foot roller to more than $60,000 for an 85-foot model. Some producers have built their own land rollers in their farm shops at less cost.

While rolling can make harvest easier, the economic benefits of rolling soybean are difficult to document.

There’s no doubt the ability to harvest is an important benefit to farmers, especially when working long hours and combining in the dark. However, it’s difficult to put a precise dollar amount on the value of easing harvest.

Recommendations

Balance the improved harvesting conditions and peace of mind that rolling offers with the damaging effects of rolling on soil quality and the additional expense.

If you decide to roll

- Confine rolling to rocky fields and flat fields with low erosion risk.

- If soybeans have emerged, roll as early as possible (before the third trifoliate stage) to minimize plant injury and allow more time for plant recovery.

- If you roll erosion-prone fields, roll before planting or wait until soybeans are in the first trifoliate stage. Erosion risk is the greatest right after planting.

- After emergence, roll in the afternoon, during the heat of the day, when soybean plants are flexible.

- Control wheel damage by configuring tractor tires and roller width to minimize plant injury.

- Don’t roll when the soil surface is moist to reduce the risk of crusting or sealing and soil sticking to the roller.

- Avoid rolling when plants are damp because they can stick to the roller and be pulled out of the soil.

- Avoid rolling when it's windy because residue can easily be moved to ditches and neighboring fields.

- Don’t use rolling in an attempt to level soil ruts.

Acknowledgements

We'd like to thank the Minnesota Soybean Research and Promotion Council, cooperating producers, crop consultants and equipment representatives for their cooperation and support.

Reviewed in 2018