Yield differences from soil tillage are more often the exception rather than the norm. This is particularly the case for soybean yields, as well as rotated corn systems.

Due to the costs associated with soil tillage and the number of extra passes on fields, reducing soil tillage is a great way to cut costs, labor and soil erosion, while promoting soil health and getting the same crop yields.

Farmers see an immediate benefit to leaving crop residues on the soil surface in regions with annual rainfall less than 20 inches due to soil moisture conservation. However, farmers are often reluctant to farm with more crop residue in Minnesota and the eastern Dakotas, where higher precipitation, cool springs and short growing seasons are common.

The primary concern is the potential for slower crop growth and reduced yield due to cooler, wetter soils in the spring. Crop residue management is even more challenging when corn follows corn, or on poorly drained soils with a high clay content.

Higher residue doesn’t mean lower yields

Study 1: Tillage effect on yield and residue

Research by the University of Minnesota and North Dakota State University showed that reduced tillage systems increased crop residue cover and reduced soil erosion while having a minimal effect on crop yields. These results are often accompanied by lower tillage management costs (equipment, fuel and labor) compared to aggressive tillage systems.

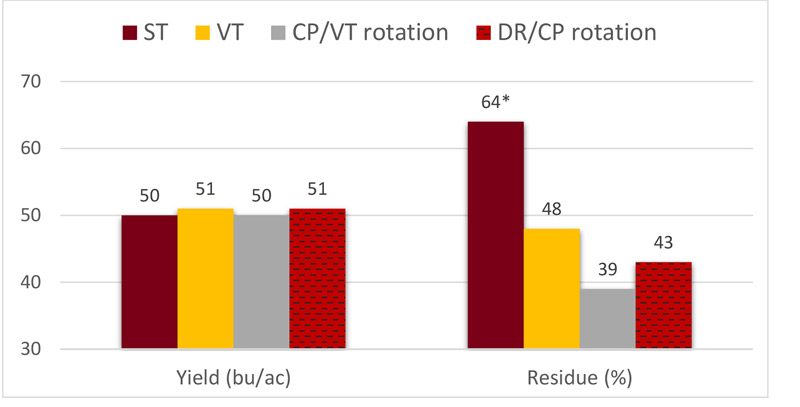

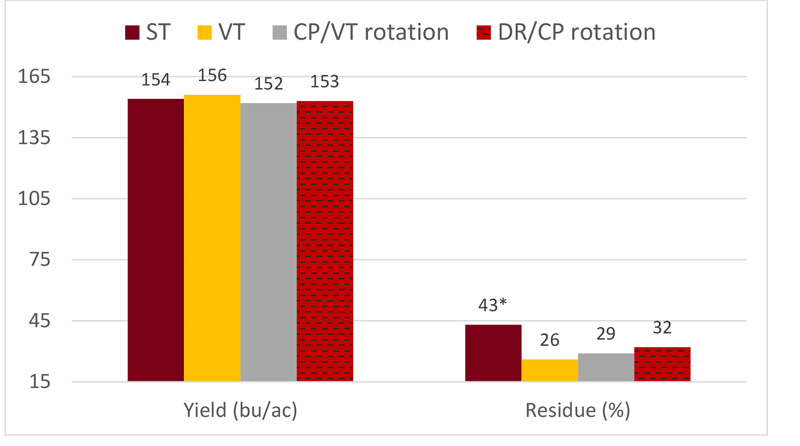

On-farm studies were conducted by University of Minnesota researchers from 2010 through 2012 in west-central Minnesota near Clarkfield. They compared four full-width tillage systems with varying crop residue levels in a corn-soybean rotation.

Tillage treatments included the following:

- Strip-till (ST): A fall strip-till treatment consisted of fluted coulter and residue managers, followed by a mole knife that operated 6to 8 inches deep, followed by notched coulters that built a 3- to 4- inch berm.

- Vertical-till (VT): Fall vertical-till pass plus a spring vertical-till pass. Either large wavy coulters or a gang of coulters operated at less than 4-degree angle.

- Chisel plow/vertical-till (CP/VT) rotation: Fall chisel plow plus spring field cultivation before planting corn rotated with a fall vertical-till pass, plus a spring vertical-till pass system before planting soybeans.

- Disk rip/chisel plow (DR/CP) rotation: Fall disk rip plus spring field cultivation before planting corn rotated with fall chisel plow, plus spring field cultivation before planting soybeans.

Results: Yield and residue levels

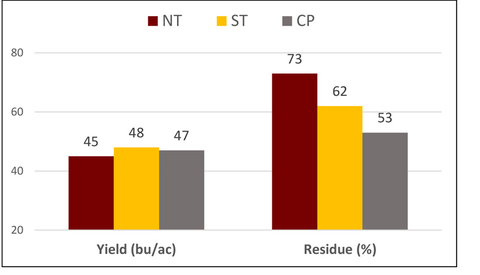

Corn and soybean yields weren’t affected by the type of tillage system in this study, although tillage costs were substantially lower with strip till. However, the type of tillage did affect crop residue levels.

Strip-till retained the highest crop residue cover following both corn and soybean planting, while the chisel plow/vertical-till rotation had the lowest residue levels following corn and soybean planting (Figures 1 and 2).

Results: Costs and profitability

These data show Minnesota growers can increase profitability with reduced tillage (Table 1). In this study, costs per acre for a two-year corn and soybean rotation ranged from $29.20 for strip-till to $48.70 for fall disk rip and chisel plow rotation.

Strip-till saved $19.50 per acre over the DR/CP rotation with no loss in yield. By changing to strip-till, a farmer could save almost $20,000 for a two-year corn and soybean rotation on a 1,000-acre farm.

Table 1: Calculated tillage costs per acre using four different tillage implement options in a corn and soybean rotation near Clarkfield, MN.

| Tillage system | Corn year cost/acre |

Soybean year cost/acre |

Two-year rotation cost/acre* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strip-till | $14.60 | $14.60 | $29.20 |

| Vertical-till (two-pass) | $19.70 | $19.70 | $39.40 |

| CP/VT rotation | $20.50 | $19.70 | $40.20 |

| DR/CP rotation | $28.20 | $20.50 | $48.70 |

*Costs include tractor, fuel, labor, depreciation on new implement, parts and repair.

Study 2: Tillage effect with different soil types

In 2014, University of Minnesota and North Dakota State University established at two farms near Barney, ND and Fergus Falls, MN, and a third farm in 2015 near Mooreton, ND. The soil series at these farms included sandy, loamy, and clayey textures, providing local farmers with a realistic picture of low-tillage impacts on their own acreage.

Four tillage systems were used:

- Chisel plow with a field cultivation

- Strip till with a coulter

- Strip till with a shank

- Vertical tillage.

Study results

systems near Barney, ND and Fergus Falls, MN during 2016 and 2018.

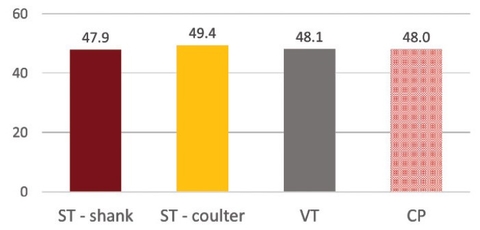

Results showed that yields were not affected by tillage method from 2015-18.

Soybean yield

There were no statistical differences in soybean yield for the various tillage implements (Figure 3). Soybean yield was not affected by tillage at any of the farms during the four growing seasons, except on the farm with sandy soils in 2018 (Tables 2 and 3). At that farm, both strip-tills yielded 3.7 bushels per acre more than either chisel plowing or the shallow vertical till.

Table 2. Soybean yields under different tillage operations in Fergus Falls, MN and Barney, ND during 2016 and 2018. Numbers in the same column with the same letter are not statistically different.

| Tillage operation | Fergus Falls 2016 |

Fergus Falls 2018 |

Barney 2016 |

Barney 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bu/a | bu/a | bu/a | bu/a | |

| Chisel Plow | 49 a | 51 a | 53 a | 39 b |

| Strip-till with shank | 50 a | 47 a | 53 a | 42 a |

| Strip-till with coulter | 49 a | 51 a | 54 a | 44 a |

| Vertical tillage | 52 a | 53 a | 49 a | 39 b |

Table 3. Corn yields under different tillage operations in Fergus Falls, MN and Barney, ND during 2015 and 2017. Numbers in the same column with the same letter are not statistically different.

| Tillage operation | Fergus Falls 2016 |

Fergus Falls 2018 |

Barney 2016 |

Barney 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bu/a | bu/a | bu/a | bu/a | |

| Chisel Plow | 200 a | 191 a | 152 a | 198 a |

| Strip-till with shank | 194 b | 185 a | 150 a | 192 a |

| Strip-till with coulter | 199 a | 189 a | 155 a | 201 a |

| Vertical tillage | 201 a | 184 a | 155 a | 198 a |

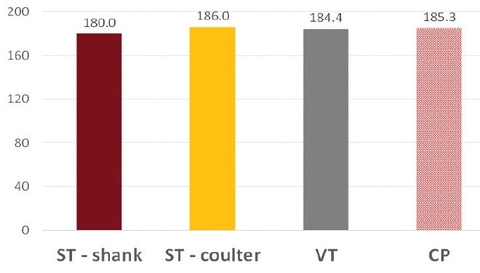

Corn yields

systems near Barney, ND and Fergus Falls, MN during 2015 and 2017.

Yield differences were observed in corn during some years, but these differences were not consistent year-to-year, farm-to-farm, or among the tillage practices. Instead, benefits or consequences to corn yields were explained by whether timely fertilizer application and placement was done or whether soil conditions were too wet for proper tillage operations (Figure 4). These results show that crop producers can do less tillage, leave more residue on the soil surface, and not affect their yields

Study 3: Small plot tillage studies

Between 2005 and 2012, North Dakota State University conducted small plot tillage studies at three locations in North Dakota and one location in northwest Minnesota.

In Fargo, ND the tillage treatments included chisel plow (two passes with a chisel plow and one field cultivation), strip till, and no tillage on a clay loam soil. For four out of the five years in Fargo, corn yield was not affected by tillage method (Table 4).

At Carrington, ND the treatments included aggressive tillage (two fall passes with a roto-tiller and two spring field cultivations), fall strip till, and no tillage on a loam soil in a wheat, corn, soybean rotation. There were no yield differences due to tillage over the five years of the study.

At sites in Prosper, ND and Moorhead, MN the tillage treatments included chisel plow (fall chisel plow with a spring field cultivation) and strip till. During the four years at Moorhead, strip till had an average soybean yield advantage of 7 bushels an acre (Table 4). In contrast, chisel plow had an average soybean yield advantage of 4 bushels an acre at Prosper(Table 4). For corn during the four years at both locations, strip till had an average yield advantage of 14 bushels an acre (Table 5). If corn was priced at $6 a bushel, strip till resulted in a profit increase of $84 an acre, while reducing the cost of additional tillage passes and maintaining more residue.

Table 4: Average soybean yields for three tillage systems at four locations in North Dakota and Minnesota during 2005 to 2012 (Nowatzki et al., 2011).

| Tillage system | Soybean yield: Fargo 5 site-years |

Soybean yield: Carrington 4 site-years |

soybean yield: Prosper 4 site-years) |

Soybean yield: Moorhead 4 site-years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bushels per acre | bushels per acre | bushels per acre | bushels per acre | |

| Chisel plow | 28 | 28 | 52* | 33 |

| No-till | 29 | 29 | '-- | '-- |

| Strip-till | 29 | 30 | 48 | 40** |

*Chisel plow yields were statistically higher in one of the four years.

**Strip-till yields were statistically higher than chisel plow yields in three of the four years.

Table 5: Average corn yields for three tillage systems at four locations in North Dakota and Minnesota during 2005 to 2012 (Nowatzki et al., 2011).

| Tillage system | Corn yield: Fargo 5 site-years |

Corn yield: Carrington 5 site-years |

Corn yield: Prosper 4 site-years |

Corn yield: Moorhead 4 site-year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bushels per acre | bushels per acre | bushels per acre | bushels per acre | |

| Chisel plot | 130 | 145 | 184 | 161 |

| No-till | 124 | 144 | '-- | '-- |

| Strip till | 128 | 145 | 198* | 40* |

*Yields were higher for chisel plow than strip-till in only the first year of the study. For the following three years, strip till had higher yields than chisel plow.

Results: Corn and soybean yields

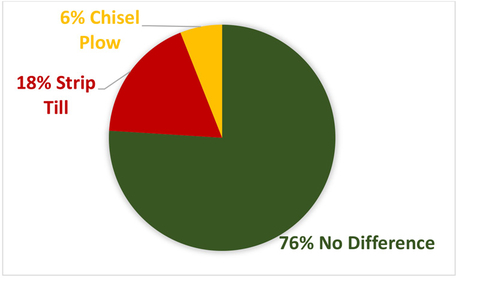

Researchers found that yield wasn’t affected by tillage 76 percent of the time when soybean followed corn (Figure 5).

In years when tillage type did affect soybean yield, strip-till had higher yields than chisel plow and no-till. In Carrington, when there was a yield difference, strip-till and no-till had higher yields than aggressive rototilling (Table 4). Among the 17 site-years, chisel plow only yielded more than strip-till and no-till during one instance (6% of the time or place).

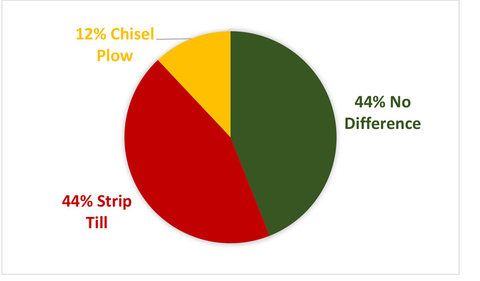

Results change slightly when growing corn following soybean or wheat. During 18 site-years, corn yield wasn’t affected by the type of tillage 44 percent of the time (Figure 6).

When tillage treatment had an effect, strip-till had higher corn yields than chisel plow and no-till 44 percent of the time. Chisel plow had higher corn yields than strip-till and no-till only 12 percent of the time. In other words, more aggressive tillage only increased yield about one out of every nine site-years.

Study 4: Southern MN tillage trials

In a separate three-year study from 2006 to 2008 in southern Minnesota, University of Minnesota researchers compared soybean yields between chisel plowing plus spring field cultivation, strip-till and no-till for fields previously planted in strip-tilled corn.

Even with the higher residue levels, the type of tillage had no effect on the soybean yields during the three years (Figure 7). This demonstrates soybean adaptability among various tillage systems.

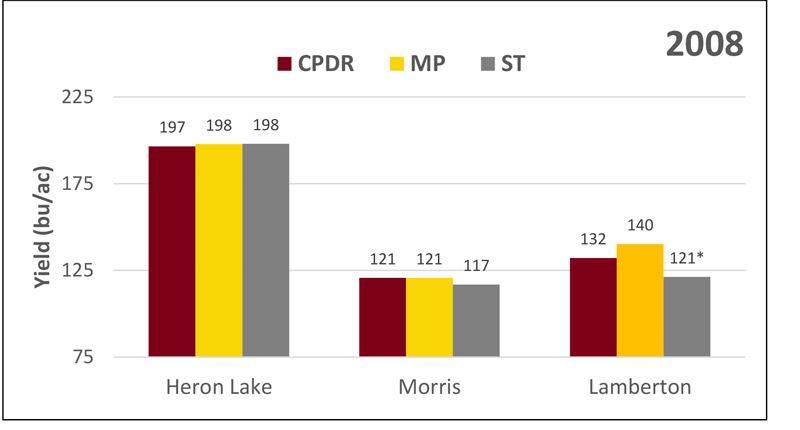

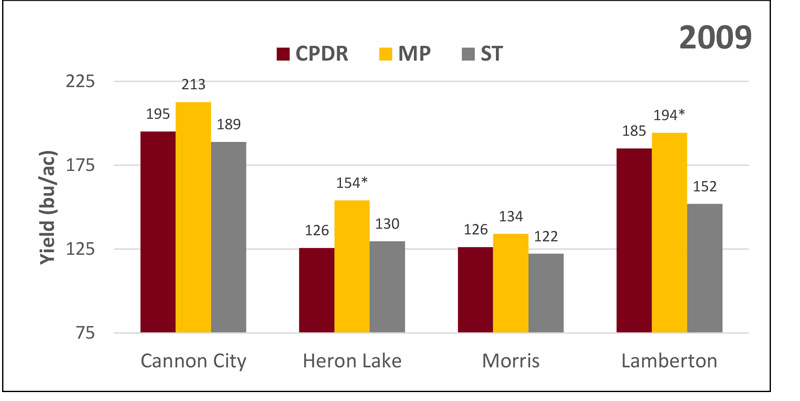

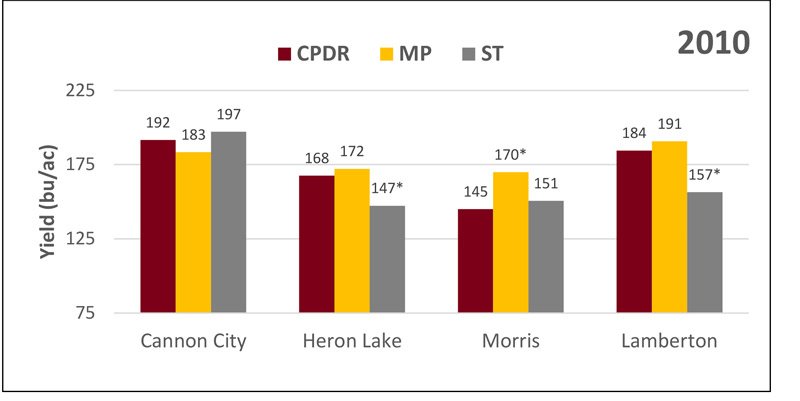

A University of Minnesota tillage study from 2008 to 2011 on poorly drained loam and clay loam soils at four sites (two located at research centers and two located in full-scale farm fields) in southwest and west-central Minnesota compared the effects of three tillage systems on continuous corn yields.

Tillage treatments included

- Moldboard plow plus one or two spring field cultivations (MP)

- Strip-till with a shank (ST)

- Chisel plow or disk rip plus spring field cultivation (CPDR).

Residue levels

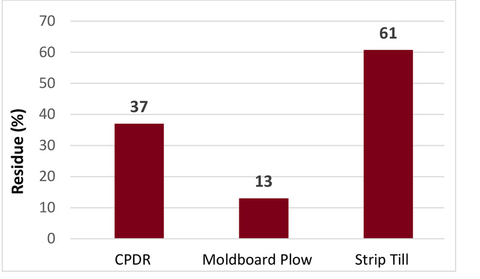

Moldboard plow had the lowest residue levels averaged over the four locations at 13 percent (Figure 8). This residue level isn’t sufficient to protect the soil from wind and water erosion, and is the system with the highest fuel and time requirement of the three tillage treatments.

The chisel plow/disk rip tillage treatment had almost three times the residue level (37 percent) than moldboard plow. This level is considered adequate to protect the soil from erosion and maintain soil productivity over time. Strip-till had the highest level of residue in the continuous corn system at 61 percent soil coverage.

Corn yields

The continuous corn yields with fall strip-till were similar to moldboard plow during the first year but lower in the second and third years, except when a secondary spring strip-till pass was performed to manage the residue and warm the soil (Figures 9 to 12).

managed with a lighter, in-line coulter implement.

Residue in the reduced tillage systems tended to build up in years two and three, covering the strip-till berm and creating a cooler environment for the seed. A second pass with a lighter, in-line coulter implement helped manage the residue and warmed up the soil similar to moldboard plow (Photo 1). Yields shown in figures 10 through 12 demonstrate this effect.

In 2009, both Cannon City and Morris plots strip-tilled in the fall received a secondary in-line coulter pass in the spring. In 2010, only the Cannon City fall strip-till received the secondary pass in the spring. In 2011, both Cannon City and Morris again received a secondary pass in the spring.

When the second pass was added to strip-till, yields were statistically the same as moldboard plow and disk rip/chisel plow.

Annual weather affects yield more than tillage

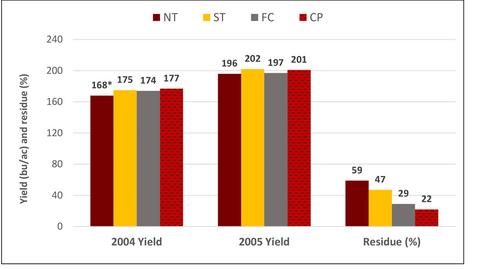

An earlier study in 2004 and 2005 across southern and west-central Minnesota compared on-farm corn yields at 13 sites for chisel plowing plus spring field cultivation, strip-till, one-pass spring field cultivation and no-till.

Tillage treatments had a larger effect on corn yields during 2004, when air temperatures were cooler than normal, than during 2005, when air temperatures were warmer than normal (Figure 13).

In a cool spring, corn with no tillage yielded six to nine bushels per acre less than corn that received tillage. However, in a warmer-than-normal year, no-till yielded the same as the other tillage systems.

The benefits of no-till included:

- An average of 2.7 times more residue than chisel plowing with a field cultivation (Figure 13).

- Lower costs per acre for equipment costs, tractor wear and tear and labor.

Averaged over two years, corn yields were similar among the chisel-plowed and strip-tilled fields while strip-till had twice the residue. These results are similar to those observed in long-term small-plot tillage trials in Waseca, where very little differences in yields have been observed among tillage systems in a corn and soybean rotation.

The perception remains that more residue will lower yields, but today's planters and drills have options to handle high levels of crop residue. Row cleaners and coulters can clear residue from the seed row and ensure good seed-to-soil contact and a warmer seedbed. Equipping the planter with starter fertilizer attachments increases the chance for consistent yields in high-residue systems.

Tillage costs

Choosing the best tillage system for your farm isn’t a “one-size-fits-all” decision. It’s similar to selecting hybrids to meet specific conditions and needs. To maintain yields, it’s not necessary to leave the field completely covered with residue to improve soil health and reduce soil erosion.

Evaluating the economics of tillage systems is very complex. Adjust tillage depth and intensity based on field factors such as

- Slope

- Soil texture

- Internal drainage

- Crop grown

- Previous crop residue remaining

Give consideration to

- Initial and maintenance costs of equipment

- Tractor size needed to pull the tool

- Equipment depreciation

- Labor costs

- Conservation program incentives

- Increased management costs related to fertilizer and pest management

In addition, there are human factors that influence the choice of tillage system, such as farming and family tradition, age, commodity markets, government programs and neighbor perception.

When selecting a tillage system, it’s important to compare differences in production costs, as well as potential yield differences. Table 6 illustrates four typical tillage options when planting soybeans into corn residue in the upper Midwest, using the 2019 University of Illinois machinery cost estimates (Table 6).

One pass of tillage can cost $14 to $21 per acre depending on the implement. When planting soybeans, costs can range from $54.90 per acre for no tillage up to $85.15 per acre for chisel plow plus a spring field cultivation. This represents a $30 per acre difference. With soybeans at $ per bushel, chisel-plowed fields would need a yield increase of more than 3 bushels per acre to pay for the tillage.

Table 6: Cost of equipment options and number of tillage passes using four management options when planting soybeans* (Source: 2019 Farm Business Management, University of Illinois).

| Operation | No-till | Vertical-till or field cultivation |

Chisel plow plus field cultivation |

Strip-till |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $/acre | $/acre | $/acre | $/acre | |

| Planter (tillage-specific) | $20.15 | $19.90 | $19.90 | $20.15 |

| Primary tillage | $0 | $14.05 | $16.45 | $17.15 |

| Secondary tillage | $0 | $0 | $14.05 | $0 |

| Combine | $34.75 | $34.75 | $34.75 | $34.75 |

| Total cost | $54.90 | $68.70 | $85.15 | $72.05 |

| Number of passes | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

*Assumes $2.50 per gallon diesel fuel.

Fortunately, research has shown soybean yields are more consistent across soil conditions and tillage options. This makes no-till a viable and economical option.

Standing stalks in no-till and strip-till maintain more surface residue, which improves water infiltration and minimizes soil erosion. No-till and strip-till farmers that leave standing stalks also lower their harvest costs by not using a chopping head.

However, farmers who have high-residue systems frequently will have residue managers on their planter. This slightly increases the cost over conventional planters.

On the other hand, corn often needs incorporated fertilizers and seedbed preparation in the spring, which requires two to four additional field passes. This adds to the overall fuel costs, labor and wear and tear on equipment.

Table 7 uses four different tillage examples farmers may use when growing corn in the Upper Midwest, and the cost of each pass.

For a majority chisel plow, disk rip or moldboard plow systems, fertilizer is broadcast in one pass and then incorporated with a secondary tillage pass in the spring. Strip-till saves a pass by applying phosphorus and potassium (nitrogen where appropriate) in the fall with the strip tiller and additional fertilizer can be applied with the planter and/or at sidedress.

Using the 2019 University of Illinois Machinery Cost Estimates, strip-till costs $37 less per acre than moldboard plow with a field cultivation in the spring. If corn is priced at $6 a bushel, moldboard plow would need a yield increase of 6 bushels to pay for the extra tillage.

A disk ripper with one pass of a spring field cultivation cost $23 more an acre than strip till, but $14 less an acre than moldboard plow. Changing your full field tillage implement to strip-till could save you $11,000 to $37,000 over 1,000 acres. Even with higher residue levels, MN and ND research shows that yields remain similar in a corn-soybean rotation, regardless of tillage method.

In some regions, no-till is an option when growing corn, especially on sandier soils or in a rotation with crops that provide very little residue. Fertilizer and lime are usually broadcast with no incorporation, and nitrogen may be sidedressed after the corn has emerged.

Table 7: Cost of equipment options using four management options when planting corn (Source: 2019 Farm Business Management, University of Illinois).

| Operation | Strip-till | Chisel plow plus field cultivation |

Disk rip plus field cultivation |

Moldboard plow plus field cultivation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planter | $/acre | $/acre | $/acre | $/acre |

| Planter | $20.15 | $19.90 | $19.90 | $19.90 |

| Sidedress N fertilizer | $11.15 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Broadcast fertilizer | $0 | $4.90 | $4.90 | $4.90 |

| Anhydrous ammonia | $0 | $12.20 | $12.20 | $12.20 |

| Primary tillage pass | $17.15* | $16.45 | $17.80 | $18.80 |

| Secondary tillage pass (1st pass) | $0 | $14.05 | $14.05 | $14.05 |

| Secondary tillage pass (2nd pass) | $o | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Combine without chopping head | $34.75 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Combine with chopping head | $0 | $40.10 | $40.10 | $40.10 |

| Total cost | $83.20 per acre | $107.60 per acre | $108.95 per acre | $124.00 per acre |

| Number of passes | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

Assumptions: $2.50 diesel, $19.00 labor, new tractor and implement overhead, not including additional cost of chopping head.

*Strip-till price includes the cost of applying fertilizer with the strip tiller. In continuous corn, strip-till may need an additional lighter tillage pass in the spring to “freshen” the berm at a cost of $11.00 per acre.

Fuel use

Reducing tillage means fewer trips across the field, conserving fuel, time and labor, and cutting machinery maintenance. The power requirement and fuel used for tillage equipment varies depending on

-

Equipment design

-

Number of row units

-

Components used

-

Soil properties

-

Shank or disk depth

-

Field conditions

-

Operator adjustments

Fuel use rises with tillage intensity, depth and increased number of passes. Effectively pulling aggressive tillage implements, such as a disk ripper or moldboard plow, requires that tractors use lower gears and consume more fuel. Using a lighter, less aggressive tillage implement can save fuel costs by operating the tractor in higher gears.

Another way to lower fuel costs is to eliminate a primary tillage pass or two secondary tillage passes.

Iowa State University fuel use study

Research from Iowa State University compared fuel usage with different tillage implements (Table 8). When comparing fuel use of implements over 1,000 acres, moldboard plowing with a spring field cultivator pass used 229% more diesel fuel (2,610 gallons) than chisel plowing with a spring field cultivation and more than 265% more diesel fuel (2,880 gallons) than strip till. Using $3.50 per gallon for diesel fuel, strip till uses $10,800 less fuel than moldboard plow and $945 less fuel than chisel plow across 1,000 acres, while maintaining similar yields.

Table 8: Fuel use and cost per 1,000 acres when using five different tillage options (Hanna and Schweitzer, 2015).

| Operation | Fuel use gallons/1,000 acres |

Cost per 1,000 acres: $3.50 a gallon |

Cost per 1,000 acres: $2.50 a gallon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shallow disking | 370 | $1,295 | $825 |

| Field cultivation | 630 | $2,205 | $1,575 |

| Strip-till | 1,750 | $6,125 | $4,375 |

| Chisel plow + field cultivation | 2,020 | $7,070 | $5,050 |

| Moldboard plow + field cultivations | 4,630 | $16,206 | $11,575 |

University of Manitoba fuel cost study

In 2015, researchers from the University of Manitoba partnered with the Prairie Agricultural Machinery Institute to calculate the cost of four tillage systems. The study compared

- Two passes with a double disk (DD)

- Two passes with vertical-till at a 6-degree angle (high-disturbance or VT 6)

- Two passes with vertical-till at 0 degrees (low-disturbance or VT 0)

- One pass with strip-till (ST)

All were pulled by the same tractor on a sandy loam soil in corn residue.

Residue levels after tillage were more than 60% for strip-till and low-disturbance vertical-till and under 30% for double disk and high-disturbance vertical till.

There were no differences in soybean yield due to tillage (data not shown); therefore, the researchers could use tractor and tillage costs alone to calculate a total cost per acre.

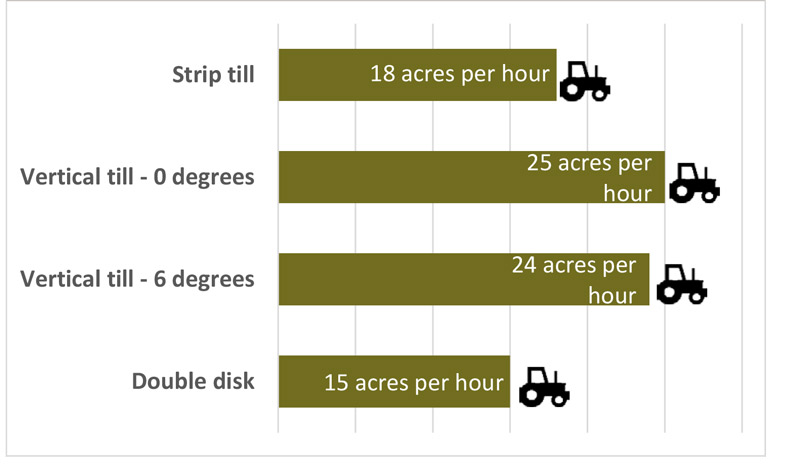

Both vertical-till units could effectively run at a higher speed compared to either the strip-till or double disk. This equated to more tilled acres per hour by vertical till, with 7 more acres an hour than strip-till, and 10 more acres per hour than double disk (Figure 14).

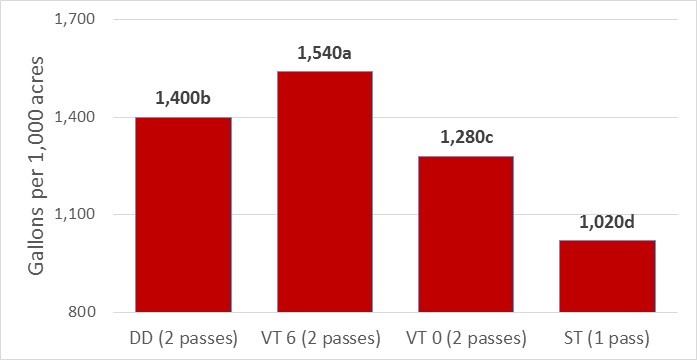

Fuel usage ranged from 1,020 gallons to 1,540 gallons over 1,000 acres, with strip-till using the least amount of fuel (Figure 15). This is due to effective corn residue management with only one pass of the strip-till equipment. Strip-till used 34% less fuel than high-disturbance vertical till.

*Columns with different letters are statistically different from each other

Another way to reduce fuel usage is to lessen the aggressiveness of the implement. By reducing the angle of the gang from 6% to 0 on vertical till, 260 gallons less fuel was used (17%). While this research was conducted on a sandy loam soil, other studies have shown that the higher the silt or clay content, the higher the draft forces, resulting in the potential for increased fuel use.

When comparing tillage systems, keep in mind the cost of fuel per implement pulled, the depth of the implement, and the number of passes across the field. Small savings can add up across each field.

Landlord benefits

Across Minnesota and North Dakota, almost half of cropland is being rented by the operator. More than 74% of that land (23 million acres across Minnesota and North Dakota) is owned by landlords who have limited to no connection to the land (Table 9).

Table 9: Rented crop acreage statistics for Minnesota and North Dakota (NASS, Bigelow et al., and Petrzelka et al.)

| State | Total cropland acres | Rented cropland % |

Rented cropland owned by non-farmers |

Total rented acres by non-farmers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minnesota | 26 million | 45% | 78% | 8.1 million |

| North Dakota | 39.3 million | 49% | 74% | 14.3 million |

Generally, land owners that have a stake in the land’s earning potential have more of an interest in soil health and conservation practices. A Utah State University study of absentee owners of farms or wooded acreage found that absentees express high environmental concern, especially those who used the land for recreation.

When asked whether conservation is important on their property, 88 percent responded yes to soil, 56 percent said yes to wildlife and 66 percent said yes to water. However, the land owner may not be knowledgeable about their options or how to find programs or farmers who share their goals.

While farmers and landowners may have conflicting views regarding conservation and production practices, using no-till or strip-till improves the long-term productivity of the soil and can represent both environmental and economic benefits for the land. It’s worth a conversation with the land owner about the benefits of reduced tillage for preserving their land legacy.

In summary, yield differences from soil tillage is more often the exception rather than the normal. This is particularly the case for soybean yields as well as rotated corn systems. Due to the cost associated with soil tillage and the number of extra passes on fields, reducing soil tillage is a great means to cutting cost, labor, and soil erosion while promoting soil health and obtaining the same crop yields.

Bigelow, D., Borchers, A., & Hubbs, T. (2016). U.S. farmland ownership, tenure, and transfer (EIB-161). United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service.

DeJong-Hughes, J. & Vetsch, J. (2018). On-farm comparison of conservation tillage systems for corn following soybeans.

Franzen, D., Chaterjee, A., & Cattanach, N. (2013). Long-term tillage studies in Fargo-Ryan silty clay loam soils in the 2011-2012 crop year. In 2012 Sugarbeet Research and Extension Reports, Fargo, ND: Sugarbeet Research and Education Board of Minnesota and North Dakota.

Hanna, M., & Schweitzer, D. (2015). Farm Energy: Case Studies - Techniques to improve tractor energy efficiency and fuel savings (Iowa State University Extension PM 3063D).

Lattz, D. and G. Schnitkey. 2019. University of Illinois Extension: Machinery Cost Estimates - Field Operations.

Nowatzki, J., Endres, G., DeJong-Hughes, J., & Aakre, D. (2011). Strip till for field crop production: Equipment, production, economics.

Petrzelka, P., Ma, Z., & Malin, S. (2013). The elephant in the room: Absentee landowners and conservation management. Land Use Policy, 30, 157-166.

Plastina, A., Johanns, A., & Wood, M. (2016). Iowa State University custom rate survey (A3-10).

Randall, G., Evans, S.D., Lueschen, W.E. & Moncrief, J.F. (1987). Tillage best management practices for corn-soybean rotations in the Minnesota River basin.

United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2012 Census of Agriculture.

Walther, P.A. (2017). Corn (Zea mays L.) residue management for soybean (Glycine max L.) production: On-farm experiment (master’s thesis), University of Manitoba.

Credits

Upper Midwest Tillage Guide is a collaboration between University of Minnesota and North Dakota State University.

Peer review provided by Richard Wolkowski, emeritus Extension soil scientist, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Reviewed in 2022