Quick facts

- Grasshopper populations are favored by long, warm autumns followed by warm, dry springs.

- Grasshoppers are an occasional economic pest of Minnesota crops.

- Five species are important in Minnesota.

- Scouting is essential to determine whether or not treatment is warranted.

Grasshopper populations are heavily influenced by climate. Long, warm autumns, followed by warm, dry springs favor the growth of grasshopper populations. A long, warm autumn favors egg-laying by grasshoppers well into September and even October in some Minnesota locations. In addition, if economically impacting grasshopper populations occurred the previous year in a variety of cropping systems, autumn populations will likely be high.

In a warm, dry spring, areas in the state that had elevated populations the previous year may face localized outbreaks. However, with early scouting and carefully applied management when necessary, grasshopper populations can be controlled and economic damage to cropping systems can be kept to a minimum.

Grasshopper populations generally do not reach outbreaks in one season, but rather build over years. Grasshopper populations also generally develop outside of cropping systems; grasshoppers prefer to lay eggs in undisturbed ground such as pastures or road ditches.

When grasshopper populations become very high, the nymphs (immature grasshoppers) eat most of the available food where they hatch. They then disperse into neighboring cropping systems to eat the available food there. Although there are 75–100 species of grasshopper on the northern Great Plains, only 5 are likely to become important crop pests in Minnesota.

Important grasshopper species in Minnesota

Early monitoring of crops for feeding damage provides enough information to make sound control decisions. All 5 economically important grasshopper species overwinter as eggs, move readily and will feed on a variety of crops. They also tend to lay eggs in ‘population production areas’ outside of crops.

Twostriped grasshopper

The twostriped grasshopper is normally the first grasshopper to hatch in Minnesota. Adults are grayish or brownish green and have two distinct yellow strips extending from the head to the wing tips. They are relatively large grasshoppers (adults are 1¼ – 2 inches long), and have a distinct black band on the top of the femur of the jumping leg. Nymphs will begin hatching in early May and be present through early July.

Migratory grasshopper

The adult migratory grasshopper is about 1 inch long, brown to gray with a distinctive black streak behind its eye. It is a strong flier and disperses readily. It is sometimes confused with the Redlegged Grasshopper but has a slight hump behind the spine on its underside, between the middle pair of legs.

Clearwinged grasshopper

The smallest of the economically important grasshoppers in Minnesota, the clearwinged grasshopper is about 3/4 inches long. It is light tan to brownish and has clear wings, distinctly marked with large brown spots.

Redlegged grasshopper

A medium-sized grasshopper, the redlegged grasshopper is 3/4 to 1 inch long and is brownish red. It has a pink to red (occasionally blue) tibia on the jumping leg. It also has a line of distinct, black spines on the hind margin of the tibia.

Although they will lay eggs and are often abundant in alfalfa, Redlegged grasshoppers cannot complete development on a diet entirely composed of alfalfa. CRP is a prime breeding and population production habitat for redlegged grasshoppers.

Differential grasshopper

A large grasshopper, adults are 1 ½ – 1 ¾ inches long and olive green to grey. The femur of the jumping leg is distinctly marked with black chevrons. They are the last economic species to hatch in spring and are most abundant in the southern part of Minnesota.

Grasshopper development during summer

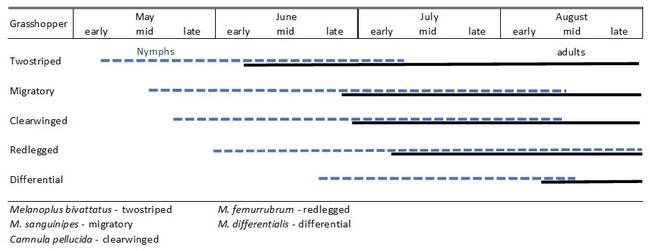

The figure below illustrates emergence and development periods for these economically important grasshopper species. As described above, the twostriped grasshopper is the first to emerge in early May, while the differential grasshopper doesn't show up until mid- to late-June.

Scouting for grasshoppers

It's essential to estimate grasshopper densities to see if populations are high enough to warrant treatment before initiating any control techniques. Scout for nymphs and adult in areas with historically high populations; last year’s ‘hotspots’ may have high populations this year. The edges of cropping systems show the earliest grasshopper feeding. Start scouting for grasshoppers at the edge of fields in late April or early May and continue through late June or early July.

To scout for grasshoppers, walk a series of straight lines either through fields or along field margins. Grasshopper action thresholds are calculated as grasshopper numbers per square yard. But grasshoppers are so active it’s difficult to count how many individual insects are in a yd2.

An alternate method of estimating grasshopper populations has been developed. As you walk, look ahead and isolate a one-foot square area (the size of a large floor tile). As you approach that square foot, count how many grasshoppers move in it. Observe at least 20 of these square foot areas. Calculate the average number of grasshoppers in these squares (total no. of grasshoppers counted in all squares / number of squares) and multiply this average by 9 to get the average number of grasshoppers / yd2. Different species of grasshoppers hatch at different times throughout the growing season, so scouting should be conducted for the entire period the crop is at risk.

Grasshopper movement

Grasshoppers move into crops from production areas and between different crops. Small grains and sugarbeet are probably the first crops at risk of grasshopper damage in Minnesota. Then as spring wheat matures and dries, grasshoppers will move to neighboring crops, such as corn. Eventually, grasshoppers will move into corn, alfalfa, and finally soybeans and dry beans as the season goes on. Agronomic practices in one crop can also initiate movement of grasshoppers. When alfalfa is harvested, for example, grasshoppers will move into neighboring crops if they are present.

These grasshoppers generally leave tilled fields to lay eggs, so grasshopper populations the following year arise outside of the field. Occasionally, redlegged grasshoppers will lay eggs in alfalfa or soybean fields. All five economically damaging grasshoppers will lay eggs in soybean and dry bean fields. As a result, it's important to monitor fields that were in soybeans or dry beans the previous season.

Management strategies

Control is generally advisable when populations reach or exceed threatening levels (Table 1). Treat crop borders when nymphs are small and numbers are moderate. Treat crop borders and grasshopper population production areas if nymph numbers are high early in the season. As nymphs get larger, move the treatment to the production site and enlarge the treated areas within cropping systems. When nymph numbers are very high (100+ / yd2), it is easier and safer to treat the production area than to allow the nymphs to enter the crop.

Timing grasshopper control depends on the potential for crop loss - especially for seedling dicots - size of grasshoppers present, and whether hatching is completed. Grasshopper control is most effective before the insects become large nymphs or adults, these stages are more mobile and harder to kill.

Grasshoppers are slow to develop resistance and so a number of different insecticide modes of action are effective (e.g. synthetic pyrethroids still tend to be effective in most areas of MN & ND). ALWAYS read and follow pesticide labels; registrations may change!

Table 1. Action thresholds for grasshopper nymphs and adults.

| Rating | Nymphs in margin |

Nymphs in field |

Adults in margin |

Adults in field |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nymphs/yd2 | nymphs/yd2 | adults/yd2 | adults/yd2 | |

| Light | 25-35 | 15-25 | 10-20 | 3-7 |

| Threatening | 50-70 | 30-45 | 21-40 | 8-14 |

| Severe | 100-150 | 60-90 | 41-80 | 15-28 |

| Very severe | 200+ | 120+ | 80+ | 29+ |

Foliar insectide for Minnesota grasshopper management

Tables 2 -10 provide labeled insecticide options for grasshopper control in major crops grown in Minnesota, as well as for roadsides and non-cropland.

Always check the product label for application rates and restrictions!

Grasshopper control is advised whenever 20+ adults/yd2 are found in field margins or 8+ adults/yd2 within the field OR when 50+ nymphs/yd2 are found at the field margins or 30+ nymphs/yd2 within the field.

Redlegged grasshoppers will sometimes lay eggs inside alfalfa fields. Consequently, infestations can sometimes arise within alfalfa fields rather than starting at the field edge.

Table 2. Foliar insecticides for grasshopper management in alfalfa in Minnesota.

| Insecticide group | Common name | Trade name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1B - organophosphates | dimethoate 4EC | Digon 400, Dimethoate 400 | |

| 1B | malathion | several | |

| 1B | phosmet | Imidan | |

| 3 - pyrethroids | alpha-cypermethrin | Fastac CS/EC* | |

| 3 | beta-cyfluthrin | Baythroid XL* | |

| 3 | cyfluthrin | Tombstone* | |

| 3 | gamma-cyhalothrin | Declare | |

| 3 | lambda-cyhalothrin | many: e.g. Warrior, LambdaStar, Paradigm, Province, Silencer* | |

| 3 | permethrin | Arctic 2EC, Permastar, Perm-Up* | |

| 3 | zeta-cypermethrin | MustangMax* | |

| 15 -benzoylureas | diflubenzuron | Dimilin | early nymphs ONLY |

| 22 - indoxacarb | indoxacarb | Steward EC | |

| 28 - diamides | chlorantraniliprole | Prevathon, Vantacor | |

| Mixtures | |||

| 28 + 3 | chlorantraniliprole + lambda-cyhalothrin | Besiege* |

*Restricted use pesticide

Grasshopper control is advised whenever 20+ adults/yd2 are found in field margins or 8+ adults/yd2 within the field OR when 50+ nymphs/yd2 are found at the field margins or 30+ nymphs/yd2 within the field.

Table 3. Foliar insecticides for grasshopper management in field corn in Minnesota.

| Insecticide group | Common name | Trade name |

|---|---|---|

| 1B - organophosphates | dimethoate 4EC | Digon 400, Dimethoate 400, Dimethoate 4EC |

| 1B | malathion | several |

| 3 - pyrethroids | alpha-cypermethrin | Fastac CS/EC* |

| 3 | beta-cyfluthrin | Baythroid XL* |

| 3 | bifenthrin | many: Capture 2EC, Sniper, Bifenthrin EC-CA, Tundra EC* |

| 3 | cyfluthrin | Tombstone* |

| 3 | deltamethrin | Delta Gold* |

| 3 | esfenvalerate | Asana XL* |

| 3 | lambda-cyhalothrin | many: e.g. Warrior II, LambdaStar, Paradigm, Province, Silencer* |

| 3 | zeta-cypermethrin | MustangMax* |

| 22 - indoxacarb | indoxacarb | Steward EC |

| 28 - diamides | chlorantraniliprole | Coragen, Prevathon, Vantacor |

| Mixtures | ||

| 3 + 28 | bifenthrin + chlorantraniliprole | Elevest* |

| 3 + 4C | bifenthrin + sulfoxaflor | Ridgeback* |

| 3 + 3 | bifenthrin + zeta-cypermethrin | Hero* |

| 28 + 3 | chlorantraniliprole + lambda-cyhalothrin | Besiege* |

*Restricted use pesticide

Grasshopper control is advised whenever 20+ adults/yd2 are found in field margins or 8+ adults/yd2 within the field OR when 50+ nymphs/yd2 are found at the field margins or 30+ nymphs/yd2 within the field.

Table 4. Foliar insecticides for grasshopper management in dry beans in Minnesota.

| Insecticide group | Common name | Trade name |

|---|---|---|

| 1B - organophosphate | acephate | Orthene 75S, Address 75S WSP, Acephate 97UP |

| 3 - pyrethroids | beta-cyfluthrin | Baythroid XL* |

| 3 | bifenthrin | many: Capture 2EC, Sniper, Bifenthrin EC-CA, Tundra EC* |

| 3 | cyfluthrin | Tombstone* |

| 3 | esfenvalerate | Asana XL* |

| 3 | gamma-cyhalothrin | Declare* |

| 3 | lambda-cyhalothrin | many: e.g. Warrior II, LambdaStar, Paradigm, Province, Silencer* |

| 3 | zeta-cypermethrin | MustangMax* |

| Mixtures | ||

| 3 + 4A | beta-cyfluthrin + imidacloprid | Leverage 360* |

| 3 + 28 | bifenthrin + chlorantraniliprole | Elevest* |

| 3 + 4A | bifenthrin + imidacloprid | Brigadier, Skyraider, Swagger* |

| 3 + 4C | bifenthrin + sulfoxaflor | Ridgeback* |

| 3 + 3 | bifenthrin + zeta-cypermethrin | Hero* |

*Restricted use pesticide

Grasshopper control is advised whenever 20+ adults/yd2 are found in field margins or 8+ adults/yd2 within the field OR when 50+ nymphs/yd2 are found at the field margins or 30+ nymphs/yd2 within the field.

Infestations in soybeans will be the heaviest on the field margins. Treating margins may lessen the numbers entering a field.

Defoliation from grasshoppers can be combined with that from other causes. Treat vegetative soybeans at 30% whole canopy defoliation. Soybeans are most sensitive to defoliation during pod development (R3 to R6). At this stage, treat plants if canopy defoliation reaches 20%.

Of greater concern is direct feeding damage to pods and seeds. Grasshoppers are able to chew directly through the pod walls and damage seed directly. If more than 5% to 10% of the pods are injured by grasshoppers, an insecticide application would be recommended.

Redlegged grasshoppers will sometimes lay eggs inside alfalfa fields. Consequently, infestations can sometimes arise within alfalfa fields rather than starting at the field edge.

Table 5. Foliar insecticides for grasshopper management in soybean in Minnesota.

| Insecticide group | Common name | Trade name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1B - organophosphates | acephate | Orthene 75S, Address 75S WSP, Acephate 97UP | |

| 1B | dimethoate 4EC | Digon 400, Dimethoate 400, Dimethoate 4EC | |

| 3 - pyrethroids | alpha-cypermethrin | Fastac CS/EC* | |

| 3 | beta-cyfluthrin | Baythroid XL* | |

| 3 | bifenthrin | many: Capture 2EC, Sniper, Bifenthrin EC-CA, Tundra EC* | |

| 3 | cyfluthrin | Tombstone* | |

| 3 | deltamethrin | Delta Gold* | |

| 3 | esfenvalerate | Asana XL* | |

| 3 | gamma-cyhalothrin | Declare* | |

| 3 | lambda-cyhalothrin | many: e.g. Warrior II, LambdaStar, Paradigm, Province, Silencer* | |

| 3 | zeta-cypermethrin | MustangMax* | |

| 15 - benzoylureas | diflubenzuron | Dimilin 2L* | Small nymphs ONLY |

| 22 - indoxacarb | indoxacarb | Steward EC | |

| 28 - diamides | chlorantraniliprole | Coragen, Prevathon, Vantacor | |

| Mixtures | |||

| 9 + 3 | afidopyropen + alpha-cypermethrin | Renestra* | |

| 3 + 28 | bifenthrin + chlorantraniliprole | Elevest* | |

| 3 + 4A | bifenthrin + imidaclopird | Brigadier, Skyraider, Swagger* | |

| 3 + 4C | bifenthrin + sulfoxaflor | Ridgeback* | |

| 3 + 3 | bifenthrin + zeta-cypermethrin | Hero* | |

| 3 + 4A | lambda-cyhalothrin + thiamethoxam | Endigo ZC* |

*Restricted use pesticide

Grasshopper control is advised whenever 20+ adults/yd2 are found in field margins or 8+ adults/yd2 within the field OR when 50+ nymphs/yd2 are found at the field margins or 30+ nymphs/yd2 within the field.

Most grasshoppers emerge from eggs deposited in uncultivated ground. Grasshoppers tend to feed and enter sugarbeet fields along field margins. Beets in fields that follow CRP, soybean, or alfalfa may have hatching throughout the field and should be monitored carefully if adults deposited eggs in the field during the previous fall. Later infestations may develop when grasshopper adults migrate from harvested small grain fields.

Table 6. Foliar insecticides for grasshopper management in sugarbeet in Minnesota.

| Insecticide group | Common name | Trade name |

|---|---|---|

| 3 - pyrethroids | alpha-cypermethrin | Fastac CS/EC* |

| 3 | esfenvalerate | Asana XL* |

| 3 | zeta-cypermethrin | MustangMax* |

*Restricted use pesticide

Grasshopper control is advised whenever 20+ adults/yd2 are found in field margins or 8+ adults/yd2 within the field OR when 50+ nymphs/yd2 are found at the field margins or 30+ nymphs/yd2 within the field.

Grasshopper infestations in sunflower tend to start at field margins. Later infestations may also develop when grasshopper adults migrate from small grain fields.

Table 7. Foliar insecticides for grasshopper management in sunflowers in Minnesota.

| Insecticide group | Common name | Trade name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 - pyrethroids | beta-cyfluthrin | Baythroid XL* | |

| 3 | cyfluthrin | Tombstone* | |

| 3 | deltamethrin | Delta Gold* | |

| 3 | esfenvalerate | Asana XL* | |

| 3 | gamma-cyhalothrin | Declare* | |

| 3 | lambda-cyhalothrin | many: e.g. Warrior II, LambdaStar, Paradigm, Province, Silencer* | |

| 3 | zeta-cypermethrin | MustangMax* | |

| 28 - diamides | chlorantraniliprole | Coragen, Prevathon, Vantacor | |

| Mixtures | |||

| 28 + 3 | chlorantraniliprole + lambda-cyhalothrin | Besiege* |

*Restricted use pesticide

Grasshopper control is advised whenever 20+ adults/yd2 are found in field margins or 8+ adults/yd2 within the field OR when 50+ nymphs/yd2 are found at the field margins or 30+ nymphs/yd2 within the field.

Earlier planted wheat crops are less susceptible to grasshopper damage. If possible, avoid planting in areas that had high grasshopper populations the previous year. Late summer tilled areas are attractive to females for egg laying (ditches, summer fallow, etc).

Grasshopper populations may migrate from wheat into neighboring crops when wheat begins to senesce.

Table 8. Foliar insecticides for grasshopper management in wheat, barley, and oats in Minnesota.

| Insecticide group | Common name | Trade name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1B - organophosphates | dimethoate 4EC | Digon 400, Dimethoate 400 | Wheat only |

| 1B | malathion | several | |

| 3 - pyrethroids | alpha-cypermethrin | Fastac CS/EC* | Wheat only |

| 3 | beta-cyfluthrin | Baythroid XL* | |

| 3 | cyfluthrin | Tombstone* | Wheat only |

| 3 | gamma-cyhalothrin | Declare* | Wheat only |

| 3 | lambda-cyhalothrin | many: e.g. Warrior II, LambdaStar, Paradigm, Province, Silencer* | |

| 3 | zeta-cypermethrin | MustangMax* | |

| 28 - diamides | chlorantraniliprole | Coragen, Prevathon, Vantacor | |

| Mixtures | |||

| 28 + 3 | chlorantraniliprole + lambda-cyhalothrin | Besiege* | |

| 3 + 4A | lambda-cyhalothrin + thiamethoxam | Endigo ZC* | Barley only |

*Restricted use pesticide

Roadside programs conducted when roadsides are generally infested and a major contributor as hatching areas can reduce but not eliminate the threat of grasshopper damage. Farmers may be disappointed if they do not make efforts to identify, monitor, and manage other hatching areas.

Roadside programs may reduce, but are unlikely to eliminate the need for additional crop protection measures in years favorable for grasshoppers. Roadside programs may contribute to, but are unlikely to be responsible for, preventing grasshoppers from laying eggs and creating the potential for problems next year.

Include scouting to determine if a sufficient percentage of roadsides are infested to warrant a roadside program. Roadside infestations are frequently spotty and other areas frequently contribute to the grasshopper problem. Treatments should generally be applied prior to significant movement of grasshoppers into fields. Movement normally begins as grasshoppers approach the 3rd instar. Treatments after adults appear are not effective. Farmers should be encouraged to scout and if necessary treat other hatching areas with threatening populations.

Table 9. Foliar insecticides for grasshopper management in roadside / non cropland used for grazing or cut for hay in Minnesota.

| Insecticide group | Common name | Trade name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1A - carbamates | carbaryl | Sevin | |

| 1B - organophosphates | malathion | several | |

| 3 - pyrethroids | beta-cyfluthrin | Baythroid XL* | |

| 3 | cyfluthrin | Tombstone* | |

| 3 | gamma-cyhalothrin | Declare* | |

| 3 | lambda-cyhalothrin | many: e.g. Warrior II, LambdaStar, Paradigm, Province, Silencer* | |

| 15 - benzoylureas | diflubenzuron | Dimilin* | Nymphs only |

| 28 - diamides | chlorantraniliprole | Coragen, Prevathon, Vantacor | |

| Mixtures | |||

| 28 + 3 | chlorantraniliprole + lambda-cyhalothrin | Besiege* |

*Restricted use pesticide

Roadside programs conducted when roadsides are generally infested and a major contributor as hatching areas can reduce but not eliminate the threat of grasshopper damage. Farmers may be disappointed if they do not make efforts to identify, monitor, and manage other hatching areas.

Roadside programs may reduce, but are unlikely to eliminate the need for additional crop protection measures in years favorable for grasshoppers. Roadside programs may contribute to, but are unlikely to be responsible for, preventing grasshoppers from laying eggs and creating the potential for problems next year.

Include scouting to determine if a sufficient percentage of roadsides are infested to warrant a roadside program. Roadside infestations are frequently spotty and other areas frequently contribute to the grasshopper problem. Treatments should generally be applied prior to significant movement of grasshoppers into fields. Movement normally begins as grasshoppers approach the 3rd instar. Treatments after adults appear are not effective. Farmers should be encouraged to scout and if necessary treat other hatching areas with threatening populations.

Table 10. Foliar insecticides for grasshopper management in roadside / non cropland that is NOT used for grazing or cut for hay in Minnesota.

| Insecticide group | Common name | Trade name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1A - carbamates | carbaryl | Sevin | |

| 1B - organophosphates | acephate | Orthene 75S, Address 75S WSP, Acephate 97UP | |

| 3 - pyrethroids | esfenvalerate | Asana XL* | |

| 3 | gamma-cyhalothrin | Declare* | |

| 3 | lambda-cyhalothrin | many: e.g. Warrior II, LambdaStar, Paradigm, Province, Silencer* | |

| 15 - benzoylureas | diflubenzuron | Dimilin* | Nymphs only |

*Restricted use pesticide

Inclusion in or exclusion from this publication does not infer any recommendation or statement of efficacy. No statement of inference of comparative efficacy is included in this document. This information is from current registration labels as available.

ALWAYS check the label for preharvest intervals, re-entry periods, further or changed information.

Reviewed in 2023